Secrets of Serenade

New York City Ballet’s Darci Kistler spins a fleet figure eight between two women on the stage of the David H. Koch Theater. “I think they’re too far away. What do you think?” she calls out breathlessly from mid-piqué turn as blue tulle whips about her legs. The music stops, and rehearsal mistress Rosemary Dunleavy corrects the dancers’ positions. The next try goes without a hitch. It’s a Wednesday afternoon in May and NYCB is preparing for the evening’s performance of Serenade, one of George Balanchine’s most seminal and beloved ballets.

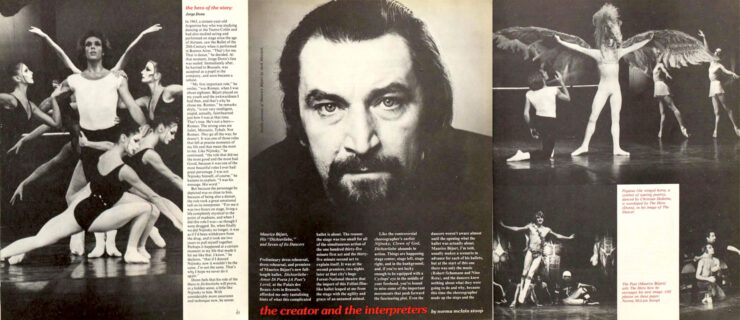

Ask someone who’s danced Serenade and they’ll probably say it’s one of their favorite ballets to perform. Ask anyone who’s seen it and they’ll most likely recall sweeping ocean-blue skirts, glorious music, and the haunting final imagery of one woman held aloft in a backward arch like the regal masthead of a ship. For these reasons and more, this neoclassical ballet for 20 women and six men has serious staying power. According to Ellen Sorrin, director of the George Balanchine Trust, the organization that controls the licensing and staging of Balanchine’s works, Serenade is one of the Trust’s most requested ballets. It is performed several dozen times a year by professional companies, university programs, and ballet schools all over the world. It is almost continually part of NYCB’s repertory and approximately two-thirds of the Trust’s several dozen répétiteurs (former dancers authorized to set Balanchine’s works) have staged Serenade.

So what makes this dance meaningful to so many, especially since Balanchine is famously remembered as insisting that Serenade is a story-less ballet—nothing more than a simple dance for women on a moonlit night? And how do today’s répétiteurs keep Balanchine’s aesthetic attainable for dancers who may have never danced a Balanchine work before?

A good place to start is with Balanchine’s choice of music for Serenade. Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings in C Major is a gem. In a short 35 minutes, joyous ripples of sound are joined with melancholy undercurrents to touch on a plethora of human emotion. Orpheus Chamber Orchestra cellist Julia Lichten has played the piece for 15 years and loves it. She considers it, she says, “restrained for Tchaikovsky, but emotionally direct at the same time, a perfect blend of the neo-classical and the Russian character.” She adds that in rehearsals, the discussion is always about the music’s motion, or, in her words, “the travel of the music.”

This makes particular sense in the work’s second movement, a flowing waltz, but the entire score lends itself to dance. In fact, in an interview for Solomon Volkov’s book Balanchine’s Tchaikovsky, Balanchine, when asked about creating Serenade, said that Tchaikovsky’s spirit guided him every step of the way. “I couldn’t do it alone,” he claimed. “I’m not smart enough for it.”

Nonetheless, Balanchine’s genius for theatrical imagery and lush, full movement pairs brilliantly with Tchaikovsky’s music and adds an entirely new dimension. “I think it was his breakthrough into the new, a glimpse of what was to come,” says former NYCB principal Maria Calegari.

Calegari danced the Dark Angel role throughout her 20-year career at NYCB and has staged Serenade since 2000. She believes the ballet’s magic starts with the opening tableau of 17 women standing awash in blue light, right palms lifted and poised outward as if to catch the moon glow of a clear night. “The female energy is set up right from the start. Then it builds and goes in and out of wonderful moments,” says Calegari.

In his book Ballet 101, dance critic Robert Greskovic goes a step further. “Taking its poetic, dramatic color from its music,” he writes, “Serenade became, for the mid-20th century, the quintessential ‘ballet of mood,’ reliving the status and impact that Fokine’s Les Sylphides had at the turn of the century.”

Given how iconic Serenade has become, it’s easy to forget that the ballet began as an exercise in stagecraft for fledgling students. In 1934, Balanchine had recently co-founded the School of American Ballet with Lincoln Kirstein and Edward Warburg. Concerned his young students didn’t understand the difference between class work and performance, he decided the best way for them to learn was to give them something new and unfamiliar to dance. He chose a favorite but obscure piece of music (the Serenade for Strings in C Major was relatively unknown in America at the time) and began creating a string of vignettes. The first class had 17 girls, hence a beginning using 17. The next class had nine students, so another segment was made for nine. When a few men joined the class, Balanchine added parts for men. As Balanchine said in an interview years later, “I didn’t have it in mind to make anything. I made Serenade to show dancers how to be on a stage.”

With an expert eye and finely tuned instincts, however, Balanchine incorporated chance moments from rehearsals. When one girl arrived late, he worked it into the dance. When a dancer fell in exhausted frustration, he told her to stay on the floor and made it into the beginning of the final slow movement known as the Elegy. On June 10, 1934, on an outdoor makeshift stage at the White Plains estate of Felix M. Warburg, the students premiered Serenade.

Over the next six years, Balanchine honed the ballet closer to the version we know today. The Tema Russo (the Russian Dance) was added for the ballet’s premiere with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in 1940. What was originally a single lead female role was made into three separate parts: the Waltz Girl, the Russian Girl, and the Dark Angel. More men were added and finally, in 1948, a theatrically cogent and sophisticated Serenade premiered with the nascent New York City Ballet. Always ready to tinker with his creations, however, Balanchine made small changes right up until the year before his death in 1983. In 1981, while working with principal dancers Karin von Aroldingen, Maria Calegari and Kyra Nichols, all of whom had the long, flowing hair Balanchine loved, he spontaneously decided that the lead women would unbind their hair for the ballet’s final movement.

Balanchine’s willingness to adjust his ballets over time presents a unique challenge for today’s répétiteurs. Although the Balanchine Trust understands that they will stage Serenade as it was when they danced it—meaning one staging might vary slightly from another—ultimately, their job is to impart Balanchine’s aesthetic to dancers who, more often than not, didn’t train at the School of American Ballet and may not be familiar with Balanchine’s works. Sandra Jennings, a répétiteur for the Trust since 1985, found this out firsthand when she set Serenade on the Bolshoi Ballet in 2010. The company had danced Serenade a few years earlier, but Jennings found that elements of their style did not match Balanchine’s. “Their upper bodies were beautiful,” she says, but she was surprised by their struggle to land softly out of jumps with the weight on the ball of the foot, without letting the heel down, an essential element for keeping Balanchine’s steps quick and light. Even tiny details such as not allowing the fingers to touch when the arms are held in the round “O” of first position had to be addressed. “But,”she says, “they ultimately danced the works gloriously.”

Bettijane Sills, a soloist at NYCB in the 1960s and currently a tenured professor at Purchase College, where she has staged Serenade at least five times, echoes Jennings’ concerns. “The biggest challenge is getting them to understand the style,” she says. For her, that means keeping the movement big without losing the lightness of Balanchine’s steps. “What Mr. Balanchine wanted is built into the choreography,” she says. “No pretense, just honest and full-out dancing.”

Calegari agrees. “I try to make the process of staging Serenade as physical and integral to the movement as possible. Mr. Balanchine loved passion and part of movement was passion to him.” Calegari, Sills, and Jennings concur that drawing out that passion from today’s dancers means encouraging them to bend lower, jump higher and move faster without looking overly athletic. Jennings works carefully with them to keep the balance between the crisp articulation of steps and a soft, feminine demeanor. “Some dancers really want to sell it to the audience,” she says, “but that doesn’t work with Serenade.”

Indeed, it is the “interior-ness” of Serenade that captivates. There is no clear story except the one imposed on the work by the viewer. Although certain moments suggest drama, such as when the Waltz Girl reaches up almost beseechingly to her partner and the Dark Angel hovers over them both, or the closing tableau when two parallel lines of women bourrée in place and lift their arms in unison as though prompting the Waltz Girl’s slow, arched ascent, it is up to the viewers to create their own interpretation.

In fact, it’s fair to say the genius of Serenade is the very thing the répétiteurs guide the dancers towards: freedom. For dancers, that freedom means discovering the interior joy—some even say the spirituality—in Balanchine’s steps. For us, the lucky audience, Serenade grants quiet access to our innermost selves and allows us to impose our private dramas on the ballet’s sublime geometry.

Lisa Rinehart, a former dancer with ABT, writes for

Dance Magazine and www.danceviewtimes.com.

Photo by Paul Kolnik, Courtesy NYCB.