The “Creative Adventure” and “Food for the Soul” of the 2024 Dance Magazine Awards

The artists celebrated at the 2024 Dance Magazine Awards have had such a broad impact that the evening felt as though it were bursting at the seams with wisdom and possibility. This was perhaps fitting, given that this year’s theme was “the stage and beyond,” recognizing artists whose work often transcends the proscenium. On Monday, dance world luminaries gathered at the Jerome Robbins Theater at Baryshnikov Arts in New York City for the ceremony (sponsored by Canada’s National Ballet School, New York City Center, Bennington College, and San Francisco Arts Commission), honoring these singular artists and humans as they offered tools and hopes for meeting the current moment.

Following opening remarks from Dance Media president Joanna Harp and Dance Magazine editor in chief Caitlin Sims—who noted that in the 70 years since the first Dance Magazine Awards, 282 artists and individuals have received them—the performance offerings kicked off with a bang: In tribute to honoree George Faison, 10 members of Philadanco! brought passion and verve to a joyous excerpt from Faison’s 1971 Suite Otis. Faison’s moves were followed by the words of another legend: Alvin Ailey, in a video excerpt from “Conversations on Black Dance,” speaking about the overwhelmingly white-led productions on Broadway, and how “every now and then, you get a wonderful Black show to come in and illuminate a dim Great White Way.” Ailey went on to describe the Tony Award–winning Faison as “an incredibly talented man” who worked on Broadway as a writer, performer, choreographer, and director.

Choreographer and historian Mercedes Ellington was on hand to present Faison’s award. She said that with all the information readily available online about the multihyphenate, she’d had to think about what she could tell the audience that only she knew. One tidbit was how she would cook short ribs of beef to bring over to his house when they were neighbors. Another was how people had to be “on their toes” to keep up with Faison’s ideas; when they worked together on a show in Europe, “George was doing everything. He produced a combination of all the characteristics of performance. It wasn’t just limited to the dance.”

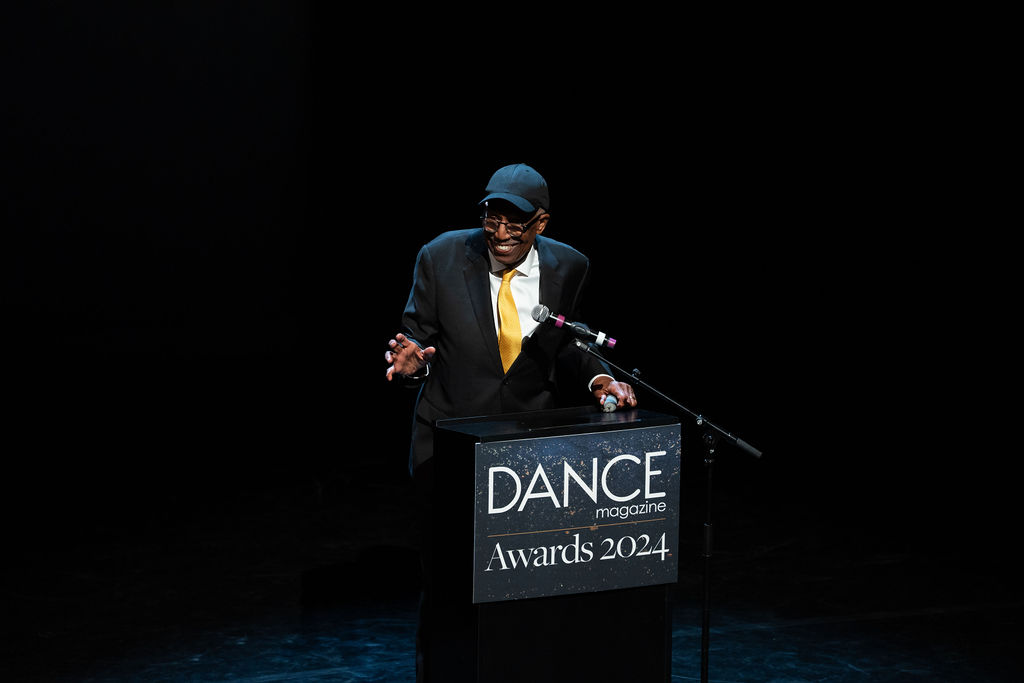

“I’m probably the luckiest person in the world, because I chose dance,” Faison opened his acceptance speech. He spoke of seeing Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater while a student at Howard University, following the company to New York City to dance, and eventually joining it himself—and how that was just the beginning of his wide-ranging career. “I’ve always lived a life of people giving me the best of what they have,” he reflected. “We all have a part to play. Life is complex. We keep changing. But not our dedication to who we are and what we are and what we’ve contributed to our wellbeing, our empathy, our compassion.” Referencing the lack of recognition and representation of Black artists that he’s pushed back against his entire career, he concluded, “You keep going, you keep hoping, and you keep trying to make people understand that you are more alike than you are unalike.”

Following a video showing excerpts of works by honoree Liz Lerman that stretched back 50 years, Jacob’s Pillow executive and artistic director Pamela Tatge took to the stage to present to the singular dance artist. “I can think of no other choreographer who has made the case better and more fluently in so many domains as to why the body should be considered, and why choreographic tools should be employed in knowing and understanding our world,” she began. She praised Lerman’s curiosity and empathy, as well as her commitment to articulating her processes and tools for others’ use, and the ways she considers the audience as an integral part of her work. In closing, she read tributes from choreographer Leah Cox (“There are no favorites for Liz. Everyone is her favorite”); scholar and fellow Arizona State University faculty member Lois Brown (“She makes space for others and in so doing, helps them make space for themselves”); and Lerman’s rabbi (“She’s made me think of religion and prayer as a form of art”).

Lerman confessed that if she attempted to thank people by name, she would inevitably forget someone, and so she asked the audience to “thank the person next to you—that way everyone is covered.” Her speech referenced collaborators across a wide range of projects, from her own company and Critical Response Process to working with Girl Scouts in Hawaii to a new project with the Library of Congress reconsidering how dance is catalogued, as well as her long friendship with Dance Magazine editor at large Wendy Perron (“We have been arguing for 50 years,” Lerman said warmly, tongue firmly in cheek). She also spoke about concepts she’s been turning over while writing her next book. One of these was reflecting on applying for the Guggenheim Fellowship 27 times before finally getting it on the 28th, how dance artists know how to fall and stand up after rejection, and her certainty that there is “information in there for the rest of the country and all kinds of people in our lives.” Another was her version of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle: “If you measure the shape of something, you will miss the momentum; if you go for the momentum, you will not be able to see the shape,” which she posits as a theory of change. “For me, creativity may be not so much of understanding shape, and understanding momentum, but understanding how we move between them,” she elaborated. And finally, how “in times of extinction, there is extreme innovation. I think we are essential in these next years,” Lerman concluded. “I hope together we’ll figure out all the shapes and all the momentums we’re going to need for our own survival, and also to protect the bodies.”

The audience was next treated to a truly one-of-a-kind performance: honoree Shen Wei improvised in silence before a projection of one of his paintings, mesmerizing in his meditative fluidity and gentle but undeniable presence.

“I have to speak after that?” former American Dance Festival director Charles L. Reinhart joked when he got to the microphone. He recalled asking Yang Meiqi, who worked in concert with ADF to create its modern dance program at Guangdong Dance Academy, why she admitted a young Shen Wei into the second year of that program when he had missed the first: “She said, ‘It was something in his eyes.’ I remember once asking Paul Taylor, Why did you take Twyla Tharp as a dancer? And he said, ‘It was something in her eyes.’ ” He also remembered choosing choreographers for ADF’s International Choreographers program in 1995, and after watching five minutes of a video of Shen Wei’s work, making the last-minute decision to add a fourth choreographer to the three-choreographer program—despite his usual reluctance to make decisions solely based on performance footage. Reinhart added that one art form was not enough for this artist; in addition to choreographing and painting, “I just found out he’s writing poetry. Enough is enough, Shen Wei!”

Shen Wei, after thanking the presenters who have helped him share his work for the last 30 years, confessed to some nervousness figuring out what he would dance tonight, cheekily adding, “The last two days, I take yoga class.” He shared that he’s been performing for 50 years now, and, “To be onstage for so many years, it’s still nice. You can so honestly share your feeling, your body, to the people. Hopefully I give people some good feelings.” Coming from a family of artists, he said, “We always believe that the most important things in our life is art. We have food, we have clothing, but more difficult is to get the best food for our soul.” What he has tried, and will continue to try to do, is “to make good food for our souls.”

Following video excerpts of honoree Joanna Haigood‘s gravity defying, deeply researched, site specific works for Zaccho Dance Theatre, Alice Sheppard spoke movingly of the choreographer’s knack for revealing “the untold, less familiar Black histories and the questions of social justice that change how we see each other. Joanna’s intimate understanding of the resilience and the vulnerability of our bodies anchors choreography that reveals the in-between, the space that we do not often perceive as active. Stories live here. People live here. The materials of these spaces hold meaning that we do not often pay attention to.” Sheppard also shared her experiences with the aerial dance community that Haigood has intentionally crafted at her studio, and how, when the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the creative process for an aerial work Haigood was advising Sheppard on, Haigood became a vital touchpoint for her as both an artist and a person.

“This is not my sweet spot,” Haigood joked when she took to the podium. “Just get me on the side of a building, I’m good. Speaking in public is a completely different thing.” She said the award was an affirmation of “the importance of work that we do as a collective. It is an extraordinary privilege to be an artist, and to be guided through life in a creative practice. It is our sanctuary—not just a means of personal solace, but a conduit through which we become better conveyers of hope, curiosity, critical thought, and presence. It provides medicine and purpose. We know art can transcend the thickest barriers. Let us believe it can rise to the challenge of this moment.” Haigood wondered aloud how we as artists can take the ideal world we imagine, which allows us to “feel safe, and free, and deeply connected,” and bring it to the broader world. One possible answer: We can use fear as a motivator and a guide. “Whether I am stepping off a high angle ledge, balancing an unruly budget, or standing in the way of an unjust aggressor,” Haigood said, “fear can be my friend. So, as I sum up this speech that I feared to make: I pray that the world finds peace. That we learn to love the planet in a way that secures a future of generous reciprocity. And that we have the opportunity to continue this wondrous and joyful life of creative adventure together.”

Benjamin Moss, from Canada’s National Ballet School, next performed the twisty, challenging “4th Psalm” from James Kudelka’s Lay Dances in tribute to honoree Mavis Staines. Melanie Person, co-director of The Ailey School, praised Staines’ leadership, citing her tenacity and commitment to changing ballet education for the better and making it something that can belong to all people. “Mavis has not only shaped the lives of countless students through her passion and expertise as former director of Canada’s National Ballet School, but she has also been an advocate for systemic change in ballet, using her platform to transform ideologies and change perspectives within dance communities worldwide,” Person said. “She understands that dance, much like life, is full of challenges, but with passion and determination, there is always a path forward.”

Staines said that starting ballet training as a young girl “felt like heaven,” but became aware as a pre-professional student that some common practices in dance education were harmful. When she led the National Ballet School, she and her colleagues pursued a dream of making ballet accessible to all and to empower aspiring professional dancers. “Regrettably,” she said, “within my own life journey, I woke up very late to the depth of racism—especially anti-Black racism—inherent in ballet’s practices, embarrassingly only five years ago. For this, I want to publicly apologize to the many generations of extraordinary artists who have battled this reality of racist practices, particularly in ballet, for their entire lives.” She ended by appealing those present to commit every day to addressing racism in ballet. “We must ensure that everyone has access and feels welcome, supported, and valued. This is what will ensure ballet evolves as an ever more dynamic and relevant language into the future. The world needs the dance world to set an example, more now than ever before, to demonstrate that systemic change is achievable.”

Tasked with speaking about the recipients of this year’s posthumous awards, Wendy Perron began by evoking the late Judith Jamison, who received a Dance Magazine Award in 1972 and was a frequent presenter at this event. “With all the tributes to the magnificent Judith Jamison now, we rarely hear about her sense of humor,” Perron noted, recalling how at last year’s Dance Magazine Awards, Jamison had been helped to the podium by two younger dancers, then turned to the audience and quipped, “I hope you all saw how I grand jetéd up here.” Perron decided to take a page from Jamison’s book and integrate a call and response, as Jamison often would in her speeches, inviting the audience to say “Thank you” to each of the late artists after Perron paid tribute to them.

Drawing on contemporary accounts and, where available, video materials, Perron evoked flamenco innovator Carmen Amaya (“an absolute hurricane onstage”), prolific performer and choreographer Talley Beatty (“He once said, I use all these steps and put a little Louisiana hot sauce on them”), hula practitioner and educator ‘Iolani Luahine (“She was said to be a wizard, a sprite, a poet, a child of the ancient Polynesian gods and goddesses”), modern dancer Yuriko (“a force in the Martha Graham constellation from the 1940s into the 21st century”), and trailblazing ballerina Raven Wilkinson (quoting Wilkinson’s advice to Misty Copeland: “Soar above the hate. Lose yourself in the music and the steps, which will live on long after bigotry has died. Defeat hatred with beauty”). Perron handed the mic to fellow Dance Magazine Awards Committee member Lydia Murray, who spoke about the final posthumous awardee, Michaela Mabinty DePrince, concluding, “Though DePrince is no longer with us in the flesh, her love will live on. It is our duty to carry her legacy forward and to keep working toward a better world.”

In the final performance of the evening, a trio of artists from The Juilliard School—dancers Haley Beck and Caden Hunter, and flutist Phoebe Rawn—performed Pam Tanowitz’s comically idiosyncratic Tête–À–Tête in tribute to Chairman’s Award recipient Mikhail Baryshnikov.

Juilliard School president Damian Woetzel confessed that he’d had a poster of Baryshnikov on his wall growing up, and recalled how unbelievable it was to find himself standing next to him at barre one day, and then to have Baryshnikov teaching him how to do a double revoltade after class. “It wasn’t about the step, I realized,” Woetzel said. “You said to me, ‘You just have to visualize it. Just see it. Then…maybe.’ ” He also remembered running into Baryshnikov at an evening class at Steps on Broadway one New Year’s Eve and asking what he was doing there: “He said, ‘Last chance of the year.’ ” Commending Baryshnikov’s willingness to take risks and inspiring so many along the way, Woetzel said, “You didn’t rest. Your curiosity, your voracious appetite—all along you were creating a platform for what might be. All these years of projects and then the founding of this center, dedicated to the possibility, creativity, collaboration, space for risk, for what you once called ‘divine insecurity.’ This sacred place that is a place of growth.” He concluded, “I can’t wait for what’s next. I am so honored to be in your wake, always and forever.”

“Speaking of ‘divine insecurity,’ ” Baryshnikov joked when he reached the podium. “It is hard to avoid clichés in these situations. But I am truly honored to be a part of tonight’s group of recipients. Each one of them is a dedicated champion of the arts and I am proud to be included in their company.” He said that when he began working to open Baryshnikov Arts 25 years ago, “I never, ever thought that it would enrich my life in the ways it has. I have met and worked with dozens of extraordinary individuals, and their courage, tenacity, and dedication to the arts has kept Baryshnikov Arts financially strong and artistically brave. Most of you know that this is not easy to do. And it can often be discouraging, but now more than ever, keeping our arts institutions healthy and curious is worth fighting for.” He quoted James Baldwin: “Artists are the only people in a society who will tell that society the truth about itself.” He said that his organization was one of thousands that exists “to help artists find and express such truth. I am happy to commit whatever energy I have left ensuring that the arts and the artists will always have a place in our city, and in our country.”