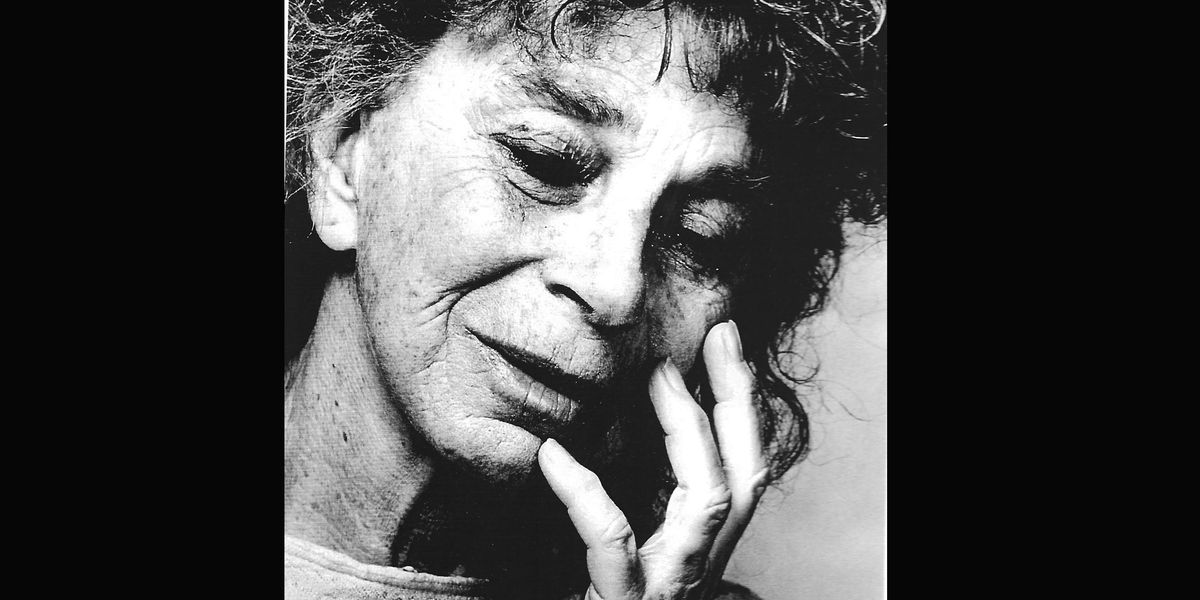

Experimental Dance Visionary Anna Halprin Dies at Age 100

Anna Halprin, the source of many of the ideas in experimental dance of the last 60 years, passed away at age 100 on May 24. Her teachings strongly influenced Judson Dance Theater, site-specific dance, somatic dance practice and community rituals. For her, dance was something to bring out of the theater and into our daily lives. She performed in streets, meadows, hotels and abandoned airports. She believed that dance was for every body. She was a visionary thinker and healer, and her radiance shone through her plainspoken, yet sometimes comically honest, language.

Born into a Jewish immigrant family in a Chicago suburb, Halprin showed a love of dance and of adventure from an early age. She attended the University of Wisconsin—Madison, where she studied with Margaret H’Doubler. As she often told the story, she walked into a classroom and when she saw a human skeleton, she walked back out. She thought she was in the wrong place for dance, but it turned out to be the exact right place for her. H’Doubler had studied biology and encouraged her students to explore the motions of the body without regard to style.

Also at UW Halprin met Rabbi Max Kadushin, who was aware early on of the growing atrocity against the Jews in Europe, while most other Americans remained oblivious. This instilled in her a sense of social justice and protection of the Jewish people. As dance historian Ninotchka Bennahum noted, Halprin was influenced by Kadushin’s idea of the vitality of sacred texts and “came to see Jewish ethics as possessing corporeal form.”

In the summers of 1938 and ’39, Halprin attended the Bennington School of the Dance, the “cradle” of American modern dance. She was impressed by Martha Graham’s forcefulness but gravitated to the fall and recovery of the Humphrey-Weidman technique. She settled in the Bay Area, sharing a studio with Welland Lathrop in San Francisco, where, among their students were Murray Louis, James Waring and the former Dunham dancer Ruth Beckford.

In 1955, recognized by both Doris Humphrey and Martha Graham as unusually talented, Halprin was invited to participate in a program at the ANTA festival (American National Theater and Academy) in New York that included Graham, Humphrey, José Limón, Anna Sokolow, Janet Collins and Daniel Nagrin. Halprin brought two contrasting solos: her deeply dramatic The Prophetess and the comedic The Lonely Ones.

Although her performances were lauded, she came away disillusioned by what she perceived as the conformity of codified techniques in New York, and she resolved to explore improvisation as a fresh approach. Later that year, her husband, landscape architect and urban designer Lawrence Halprin, built an outdoor deck for her at their home on the side of Mount Tamalpais in California.

In my interview with her in 2010, Halprin explained her passion for dancing within nature: “Being outside, you naturally expand. My deck meanders among the redwoods, so there’s no front, back, side, side. There is no center; you are the center.” During another workshop that I observed, she gave this image: “When you stand, think of yourself as a tree, with your roots under the ground. Jounce until you feel solid enough that no one can lift you.”

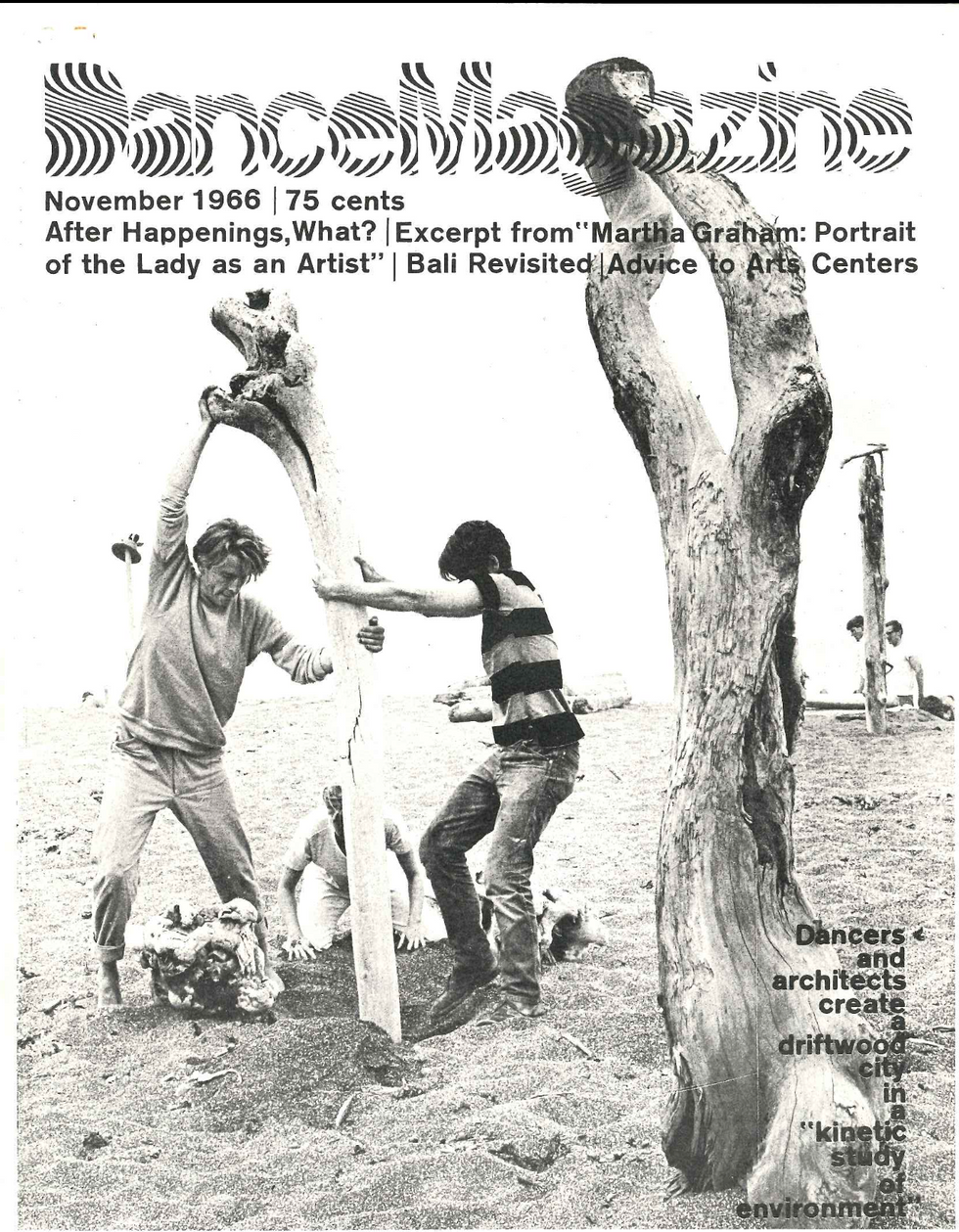

Halprin’s project Driftwood City on the November 1966 cover of Dance Magazine

Once Halprin started concentrating on task-based improvisation, Simone Forti became her protégée. In 1960, Forti, Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown and June Ekman, came to the summer intensive on her deck. (Meredith Monk attended later sessions.)

Halprin was a strong influence on these women artists. In the early 1960s, when Rainer, and Brown and Forti helped create Judson Dance Theater in Greenwich Village, they brought with them some of Halprin’s values. For example, as Forti has said, their teacher was always looking for a way to release a “surprise to the imagination.” Forti also said that Halprin urged that “we should base our work in the experience of sensation. That has some roots in how California absorbed Zen—mainly from Shunryu Suzuki, whom all the beat poets studied with.” It was Forti who carried Halprin’s interests cross country to New York, fueling the Judson rebellion.

In addition to working with beat poets like Michael McClure and Richard Brautigan, Halprin collaborated with avant-garde musicians like La Monte Young and Terry Riley and visual artists like sculptor Charles Ross. She helped create the collaborative environment of the Bay Area.

Halprin was friends with Merce Cunningham and John Cage. Both Cage and Halprin, perhaps coincidentally, shared a philosophy about blurring the line between art and life—though with very different styles. She brought everyday life into her works, like Apartment 6, for which she created a domestic setting—with a dollop of the absurd. And she brought dance into her everyday life. “Anna has always had a phenomenal way of creating ritual out of life passages,” Janice Ross recalled recently in In Dance.

Halprin’s best known work, Parades and Changes (1965–67), with a music score by Morton Subotnick, toured Europe before it arrived in New York. The two memorable sections were “Undressing and Dressing” and the “Paper Dance.” In the first, the dancers slowly, ritualistically, took off their clothes while focusing on a spot far away. In the second, the dancers, now nude, ripped up sheets of brown paper and tossed them overhead. It was like watching a fountain shooting water high into the air—or any other beautiful occurrence in nature. When the piece came to The Playhouse at Hunter College in 1967, the buzz about the nude section caused the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office to prepare a warrant for the arrest of the company on charges of indecent exposure, but there was no follow up. Yet that brush with the law opened up nudity to Broadway: Jacques Levy, who was in the audience at Hunter, directed Oh! Calcutta! (1969), with its famously nude dance sequences. (Needless to say, his version was more lucrative.)

In the late ’60s, after many urban areas, including the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, saw riots because of racist discrimination, Halprin created Ceremony of Us. She brought together her mostly white San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop with a group of Black performers from Studio Watts of Los Angeles. She led them through a week-long process of exhaustive, sometimes confrontational improvisations. Starting with separate lines of the Dancers’ Workshop on one side and the Watts group on the other, she gradually integrated them through rhythm and improvisational scores. As they meshed with each other, they also became more abandoned and more intimate. (A half-hour KQED documentary, Right On, reveals this part-joyful, part-harrowing process.)

The critical reviews of Ceremony of Us were disappointing, causing Halprin to feel that perhaps her strength lay more in leading workshops and less in creating a performance for the public. Process rather than product—a very ’60s concept.

In 1972, Halpin was diagnosed with cancer. She went through surgery but she believed what ultimately healed her was a psychological process in which she felt compelled to dance out her dark side. In Anna Halprin: Experience as Dance, Ross writes, “Anna’s cancer had presented her with the ultimate challenge to her faith in the body as the basis of performance truth. By detonating her emotions in her dance, Anna hoped to purge herself of her disease itself.”

This powerful experience led to the development of the Life/Art Process, which her daughter Daria, an expressive arts therapist, still teaches at the Tamalpa Institute. From healing individuals she expanded her process to healing communities. When Marin County was plagued with a serial killer, Halprin led a community ritual to dispel the danger. Coincidence or not, the communal event was followed by the capture of the murderer. In ensuing years, Halprin refined the ritual as the concentric circles of what is now known as the Planetary Dance in which each person proclaims the cause they will fight for before running or walking in those circles.

The scores for these rituals, plus shorter exercises like rising and falling, active/passive, and release and restoration, are explained in her latest book, written with Rachel Kaplan, Making Dances That Matter: Resources for Community Creativity.

Halprin, the recipient of a 2004 Dance Magazine Award among other accolades, is an iconic figure in global dance. The Planetary Dance is now performed in many countries annually, and other works of hers have been reconstructed by several groups internationally. For her 95th birthday, inkBoat celebrated her life and work with 95 Rituals, offered by 95 artists from near and far.

Her 95th year was also the time when Stephen Petronio asked her to set a work on him for his Bloodlines project. He tells this story about rehearsing with her for her solo The Courtesan and the Crone:

“She said that I was too aggressive. She gave me one rehearsal note: ‘Even when you’re passive, you are controlling. Get down on the floor and roll on me.’ She seemed so small and vulnerable. But we were rolling all over each other. Then she said, ‘Stand up and now let go.’ ”

Anna Halprin was a daring dancer/choreographer, a master teacher and a pioneer in redefining dance as an art-and-life process. Spending time in her presence was a pleasure and a challenge.

Find out more about Anna Halprin:

BOOKS

Anna Halprin: Experience as Dance, by Janice Ross

Making Dances That Matter: Resources for Community Creativity, by Anna Halprin with Rachel Kaplan

Radical Bodies: Anna Halprin, Simone Forti and Yvonne Rainer in California and New York, 1955–1972, by Ninotchka Bennahum, Wendy Perron and Bruce Roberts.

Moving Toward Life: Five Decades of Transformational Dance by Anna Halprin, edited by Rachel Kaplan

Anna Halprin, by Libby Worth and Helen Poynor

FILMS

Breath Made Visible, ZAS Films, director Ruedi Gerber, now on Vimeo

Returning Home, Positive Motion

and Embracing Earth: Open Eye Pictures