Annie-B Parson Talks David Byrne, Trump and Her New Book

A master of cross-pollination, Annie-B Parson pulls material from dance, film, music, literature, theater and more into deeply satisfying dialogues. And she has a busy fall: Her new book is being published in November. Big Dance Theater, the company she leads in partnership with Paul Lazar, brings three works to the NYU Skirball Center for the Performing Arts November 8 and 9. And American Utopia, the acclaimed concert tour she choreographed for David Byrne and an ensemble of musicians, appears on Broadway from October through January.

New Musical Express said American Utopia “may just be the best live show of all time,” while The Guardian said that it “pretty much resolves the whole Cartesian mind-body split.” The Los Angeles Times said it was “quite simply, a wonder of imagination, ambition and execution, a frequently breathtaking celebration of the miracle of life.” Just curious: Who’s right?

[Laughs] Oh, wow. I just want to enjoy those responses, they’re so wonderful. But my favorite is, “resolves the mind-body split”—I’m so happy to be part of anything that nudges the form a little bit forward!

Did you have any sense how warmly received it would be?

Gosh, no. I was following David’s lead, the initial idea he’d sketched out, of 12 musicians moving in an open space without wires. I think he felt like audiences wanted to experience live humans moving, rather than “video magic.” He always has his finger on the pulse.

Ike Edeani, Courtesy Helene Davis PR

The show references images from the 1984 live concert film

Stop Making Sense. How deeply did you dig into that documentary?

So many of David’s songs have personal meanings for his fans, like anthems. That’s how a lot of us relate to great music. I don’t know that most people who aren’t dancers realize that we experience beloved dances the same way, so I gingerly suggested to David that we try to find some dance quotations. We ultimately chose an iconic dance, from “Once in a Lifetime,” and brought it back. When people see that, they remember it and do it in their seats! It’s like singing along.

Byrne’s essay about the remount states, “I thought to myself that this new context might be good—it might bring out the narrative arc a little bit more, to make it just a little more explicit.” Yet one of the things I’ve always enjoyed about your and Big Dance Theater’s work is the unease it seems to feel about making things

too explicit, about making narratives too linear or conclusive.

David is the same way and, while I don’t want to speak for him, it’s still largely non-narrative. But he talks between some songs about things he cares about and there’s an arc to that.

American Utopia

Catalina Kulczar, Courtesy Parson

Are Chris Giarmo and Tendayi Kuumba reprising their roles for the Broadway production?

They are. Chris has been involved with Big Dance projects for something like 15 years; Tendayi came to the tour later on and learned the movement that had already been developed.

Besides being the show’s two primary dancers, did they also assist you in coaching the musicians on their movement?

Associate choreographer Elizabeth DeMent does that, but Chris also serves as dance captain, so he gives notes throughout the run and re-spaces the dances on tour for different stages. Everything in the piece is choreographed and, while it might seem like it goes in and out of dance, there are specific movement directives for every performer in each song, throughout the entire show, so it takes some care and feeding to keep the details sharp.

American Utopia

Catalina Kulczar, Courtesy Parson

Are the musicians cast in

American Utopia the same individuals that would’ve been part of a more traditional tour, or was there a movement component to the audition?

I wasn’t part of that process but, as I understand it, the musicians they were considering were asked something like, “Are you up for movement?” I’m not sure some of them knew just what they would be getting into! [Laughs]

But you have choreographed for a wide range of abilities.

I’ve worked with nontraditional dancers throughout my career. Pop singers, actors, symphonies… I choreographed David Lang’s The Public Domain, for one thousand amateur singers! Working with dancers, a lot gets communicated non-verbally, but with untrained dancers you need to find a specific and deliberate language around movement because there is no shared language, no baseline. I try to put myself in their shoes. It’s important to remind myself how scary and alien dancing is to the non-dancer.

Did you use weird names as shorthand for any of the steps?

Yes, we have quite a few: The Cult Dance, Kitty Kitty 2.0, Kittens, Mittens, Hot Feet, The Flasher, Emergency Procedures, Pinwheel…

American Utopia

Catalina Kulczar, Courtesy Parson

Turning now to the Big Dance triple bill at Skirball:

The Road Awaits Us and Ballet will be performed for the first time in North America, correct?

Yes, although Ballet is a working title. We don’t legally have to change it, but I did recently learn that Trisha Brown has a piece called Ballet.

Tell us what you find so interesting about

Agon, one of your sources for Ballet.

I love it because you can still feel the heat and the blood of the experiment within it. Balanchine, like the early postmodernists of the same moment, was interested in “thing-ness”—by which I mean the material itself, rather than our ego in relation to the materiality of movement, in reaction to the personality-driven, angsty work of the earlier 20th century. Even today, Agon retains that sense of newness. It continues to feel relevant, which is rare in live theater, as opposed to works of visual art, which seem to endure longer.

Is there a role or section from

Agon that you imagine yourself dancing?

Oh, gosh. I love the duet, with those long diagonals. I don’t know whether I’d be the man or the woman. Can I be both?

Big Dance Theater’s Elizabeth DeMent and Ogbitse Omagbemi in Annie-B Parson’s Ballet

Xavier Cousens/NYU Center for Ballet and the Arts, Courtesy Helene Davis PR

Of course. I gather from the title

Cage Shuffle: Redux there might be some changes since the last time Paul Lazar performed it, as Cage Shuffle.

He’s doing only the first half of it, as a sort of curtain-raiser. He’s performed it a lot, all over the world—he just did it in Romania for a group of army recruits in a drill hall! Paul asked me for some new dance material to preserve the complexity of the challenge.

The work draws heavily from

Indeterminacy, a series of one-minute stories by John Cage which essentially amount to, “Do this, or not, it’s up to you.” How is that different from “Do whatever you want?” And how does the result end up having anything to do with Cage?

It’s similar to when I work for David—my sense of his aesthetic is my frame for creating material for him and so, although he’s not prescribing what I do, it still has that aesthetic imperative. I think Cage’s entire history is embedded within the Cage directives; they’re not “free,” so to speak, like an open door away from tradition. They have that frame around them and, because of the way Cage writes, I wanted it to be noun-y, rather than verb-y. And the noun-iness lives within the framework of my perception of Cage’s work. So it’s kind of the opposite of, “Anything can happen.”

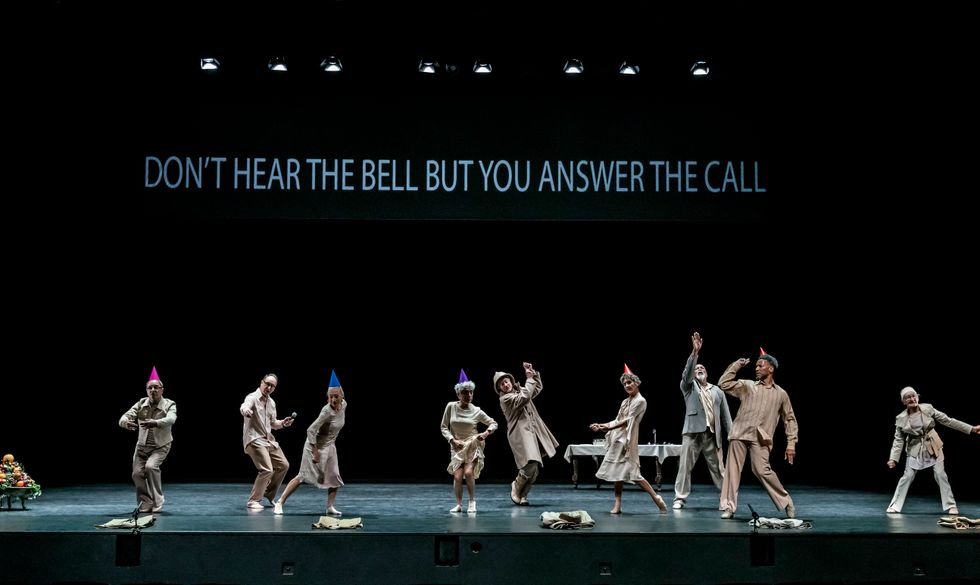

Annie-B Parson’s The Road Awaits Us

Johan Persson, Courtesy Helene Davis PR

How did you choose the artists for the birthday party in

The Road Awaits Us?

We originally did the piece for Company of Elders in London. Those “retired” dancers were largely from the London ballet and modern scenes, companies that branched off from Graham. New York City has this rich history with postmodernism—a different family tree, in my opinion—and so, for the version we’re doing here, we have Sheryl Sutton, who did early Robert Wilson work; Black-Eyed Susan, the genius performer who was with Charles Ludlam; and George Faison from Alvin Ailey. We have dancers from Cunningham, and from Yvonne Rainer, and we have Bebe Miller! It’s a feast of a cast.

How does

The Bald Soprano fit in?

When I received the commission from London, it was right after Trump got elected, and I wanted to be honest about the confusion that I felt as an American. Who were these people who would vote for him? Who was I in the equation? Eugène Ionesco’s absurdist language felt tonally right for that moment as a jumping-off point. But, as in my other text-based pieces, I created a very skeletal edit of the play. I removed all the narrative, and we end with the farewells from Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard.

Birthday parties, farewells, late-career dancers: Sounds like it’s a lot about mortality.

Yes. Maybe it’s an absurdist celebration around the end of things. There’s a restart in The Bald Soprano, at the end of the play, but I didn’t want to include that, either.

We don’t get to start over.

Right. We don’t.

Annie-B Parson’s The Road Awaits Us

Johan Persson, Courtsey Helene Davis PR

I’ve been reading about Byrne’s project

Reasons to Be Cheerful. What are some of yours?

Oh, that project is beautiful—he’s the consummate citizen-artist of our time, I think. What are some of my reasons to be cheerful? Working with David is one of them. My family. Dance. Being part of the history of the body. I recently read a poem by Gregory Orr, which asks, “If we’re not supposed to dance, then why all this music?” Dance is the animation of our body and choreography is the aesthetic organization of that animated body in space. I feel cheerful just thinking about that!

Those are all the questions I have, so thank you.

Thank you—this might be the first time I’ve ever had the chance to talk about Big Dance and David at the same time. Those worlds very rarely overlap. I’d kind of like to mention a third thing, if that’s alright.

Of course! Go ahead.

I have a book coming out this fall, Drawing the Surface of Dance: A Biography in Charts, published by Wesleyan University Press. It’s drawings and charts of my choreography and also serves as a generative book for art making and, in the book, those worlds interact for sure. To me, it’s all one dance; I don’t differentiate between working with Big Dance and working with David and working on a play where I’m the choreographer or whatever. They’re all an exploration of this incredible charge to “make dances,” with different directives and imperatives, different requirements and freedoms, and different frames. The book holds all of that.