What Would It Take to Change Ballet’s Aesthetic of Extreme Thinness?

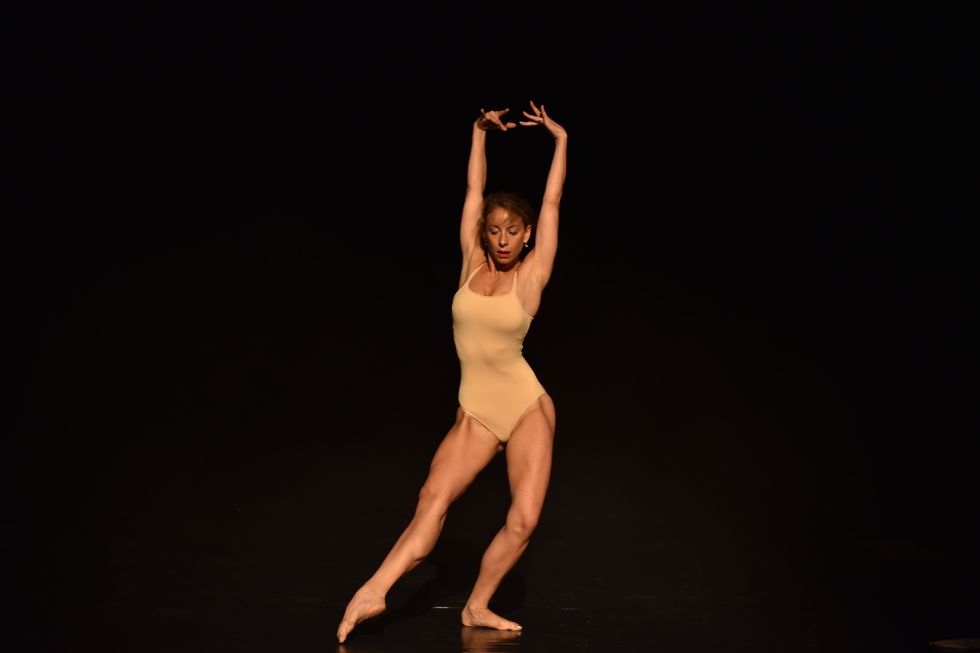

As a student, Maria Caruso was told that her body might be better suited to modern dance than ballet. “But I didn’t want to give up my pointe shoes,” she says. “So then I was told to get a breast reduction. To change the way my body looks. And I just didn’t understand that. Why am I being discriminated against for my body shape, if I’m athletic and I have the technique and the artistry?”

Caruso went on to found Pittsburgh’s Bodiography Contemporary Ballet, a company dedicated to showcasing dancers with non-stereotypical ballet bodies. However, as chair of the performing arts department at La Roche University, she knows she can’t pretend that students of all body types have the same shot at getting placed in ballet companies. Proportions still matter, and in a field full of type A personalities, dancers who don’t have the “perfect” body are often made to feel as though they’re simply not working hard enough.

Metamorphosis Ofir Zaguri, Courtesy Caruso

“There’s so much competition for jobs that companies can easily choose dancers with the body types that approach most closely their ideal,” says dance historian Lynn Garafola. She adds that while men do experience certain aesthetic pressures, the range of acceptable body types for male ballet dancers has always been broader than that for women, and has continued to widen in recent years. Yet female ballet dancers are still held to drastic standards.

Extreme thinness predominates—and dancers are harming themselves trying to achieve the look. The continued preference for ultrathin bodies seems particularly out of step with current cultural conversations around body positivity and acceptance. What would it take for ballet body standards to change?

The Fashion Link

Many see the ballerina as a timeless and unchanging figure. However, the “ideal” ballet body has changed significantly throughout history, notes Garafola. “In the 1880s and 1890s, ballerinas were always corseted, with tutus that looked almost like they had bustles in the back. It was very much an hourglass figure. That was the fashion ideal of the time,” she says.

Garafola traces the slimming down of ballet dancers to the early 20th century, particularly the 1920s, when the boyish flapper look was all the rage. After World War II, there was another period of intensifying thinness, particularly among European ballet companies that had close ties to high-fashion designers. George Balanchine, often cited as the originator of the ultrathin look, may have been influenced by the time he spent in Paris in the 1950s, says Garafola, as well as the emergence of extremely thin supermodels like Twiggy. Starting in the ’90s, many dancers started to do more cross-training, leading to bodies that were still thin but more visibly muscular.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Ballet has historically been slow to embrace new trends, but it is possible the art form may follow fashion’s example again. While very thin models are still the norm, in recent years many brands have won acclaim and commercial success by using models with a wider variety of body types. This path may appeal to ballet companies, who are facing the problem of declining and aging audiences.

“People want to see themselves reflected onstage,” says Ebony Williams, a dancer whose career spans from contemporary ballet to commercial work to Broadway. “I think embracing more body types would help bring a massive audience back to ballet.” Though little data exists on the subject, one study found that balletgoers in the UK cared more about dancers’ technical facility than their size.

Busting Long-Held Myths

When dancers are pressured to lose weight, it’s often presented as health advice, despite advancements in dance science that prove thin doesn’t always mean healthy. Meaningful change would involve educating—or reeducating—those in positions of power, including teachers and artistic directors. Rather than passing down conventional “wisdom,” says dietitian Rachel Fine, MS, RD, CSSD, companies and schools should rely on dance-medicine experts.

She adds that the practice of weighing dancers needs to end, period. “It’s simple. Muscle weighs more than fat, and dancers should have muscle. That may lead to higher numbers on the scale. It doesn’t reflect anyone’s capabilities in the studio,” she says.

Extreme thinness is an aesthetic preference—not a prerequisite for good technique. “There’s simply no scientific evidence that you have to be skinny to do ballet. These are issues of tradition, not biomechanics,” says Julia Iafrate, DO, CAQSM, founder of the Columbia Dance Medicine clinic in New York City.

For example, Iafrate says it’s a myth that heavier dancers cannot dance safely on pointe because they’re putting too much pressure on their bones. “It’s your muscles that hold you up when you’re on pointe, not your bones,” she says. “If a six-foot-tall, muscular man can dance on pointe, why would a woman have to be so small to do it?”

Daniela Vesco, Courtesy Clear Talent Group

Many suggest that training correctly will transform a dancer’s body into the “right” shape. This isn’t true. The main reason ballet dancers’ bodies tend to look similar is because they were selected based on having that body type, Iafrate explains.

Another myth? The idea that female ballet dancers must be very small in order to be lifted. “You need to have the muscular strength to help hold yourself up in the air. A dancer who has less muscle because they’re so focused on maintaining a low body mass is going to be harder to lift,” says Iafrate.

In fact, Iafrate points to a 2010 study which found that dancers whose body-fat percentage was very low tended to fatigue more quickly. Fatigue, and the resulting loss of coordination and control, left them at higher risk for injury.

“Having a healthier body mass and healthier muscle balance is what’s going to decrease the likelihood of getting injured,” Iafrate says. Better educating teachers and directors by including dance science in training programs and teaching certifications could stamp out these falsehoods so they stop being passed down.

It’s Time to Diversify the Lines

Another common argument is that ballet dancers must be thin in order to display the correct “line.” But would audiences even notice the difference?

“The truth is, you can only really tell in the first 10 rows. After about row 11, all the bodies start to look the same,” says former New York City Ballet dancer Kathryn Morgan, whose nine-year battle with illness and subsequent return to the stage with Miami City Ballet led her to confront ballet’s body-image problem.

However, in order to really change, the ballet world will have to acknowledge the beauty in different types of bodies. Williams says it’s time to leave behind the obsession with uniformity. For example, though ballet companies have slowly begun to embrace more racial diversity, dancers of color who “make it” tend to be incredibly petite.

“Having more diversity in color and culture will definitely change body standards,” Williams says. “Part of keeping ballet progressive is accepting change in that visual architecture, the look of the body itself. And I hope ballet companies realize that if they allow different body types into their world, they will also discover more about movement.”

The Next Generation

In academia, Caruso sees a shift happening. “New directors coming in are shifting into a healthier approach to teaching ballet,” she says. “But honestly, I don’t know how it will change at the company level.”

Many have wondered if the small but growing number of female directors at ballet companies might usher in a new era of inclusivity. But most of these directors trained and performed under existing body standards, and may not be motivated to change them. “I think having women directors will help, but it won’t be an immediate fix,” says Morgan, noting that in her experience, some female directors are more sympathetic toward female dancers, but others are just as harsh.

Jenna Rae Herrera, Courtesy Morgan

“This is a tricky topic. It’s taboo,” Morgan adds, and admits that 10 years ago she wouldn’t have spoken explicitly about it. While many dancers are still afraid, among her generation Morgan sees more dancers willing to tackle taboo topics in public forums like social media, where they reach young dancers directly. She still sees a split among today’s teachers with only some more focused on artistry over physical appearance.

For body standards to meaningfully evolve, directors must take an active stance and cast dancers who break the current mold. Twenty to 30 years from now, when today’s dancers are at the helm of major companies, Morgan sees this as a possibility. Time will tell.