Dancing While Black: 8 Pros on How Ballet Can Work Toward Racial Equity

For years, conversations around racism in ballet were typically held behind closed doors. They took place only between company leadership and diversity consultants, and were often met with empty signifiers and performative gestures. Consequently, the dominance of white, Eurocentric ideals and aesthetics have remained as prominent as ever. Tokenism, microaggressions, biased recruitment and prejudicial pedagogy have limited space for Black artists to succeed. But the current momentum to dismantle systemic racial injustice, inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, has empowered Black dancers to use their voices to demand change.

As a professional dancer myself, formerly with Dance Theatre of Harlem and Ballet West, and currently with the Tanzcompany Innsbruck in Austria, I understand the duality of being a Black face in a white space. I’ve had the great privilege to interview exquisite Black dancers from several different ballet companies to hear their stories as well as their insights on how ballet can work towards true equity and diversity.

Rachael Parini, BalletMet dancer and creator of the Chocolate and Tulle project

Invest in education:

“Educate the board, the artistic and executive directors, and teachers about what is excluding Black artists. Also educate parents of young Black students on all it takes to become a professional. I remember my parents’ shock over the high cost of pointe shoes. Equality is not equity. We don’t just need the same opportunities—we need support, understanding and a place that is ensured.”

Avoid tokenizing:

“Being the star of the outreach performances and never used in main-company repertoire becomes internalized by the artist. They learn self-effacing behavior and want to quit.”

Don’t generalize:

“You don’t know someone’s story until you ask them. Each of our experiences is different—we’re not all the same just because we are Black. Everyone has a different struggle.”

Lawrence Rines, Boston Ballet soloist

Make sure everyone belongs:

“Tokenism begins at the educational level. Having only one or two Black students in the school leaves them feeling unsafe, and it also endorses to their white counterparts, even subconsciously, that ‘These people are in our space.’ True diversity ensures a sense of belonging, for everyone.”

Take time for training:

“Diversity and sensitivity training can work—we saw its effectiveness with the #MeToo movement. Accountability has been lacking for so long. The time is up for excuses. The current movements to demand racial justice and equality have been very inspiring. You see how many people actually care, and so many dancers are finding their voices. The human spirit is incredibly strong.”

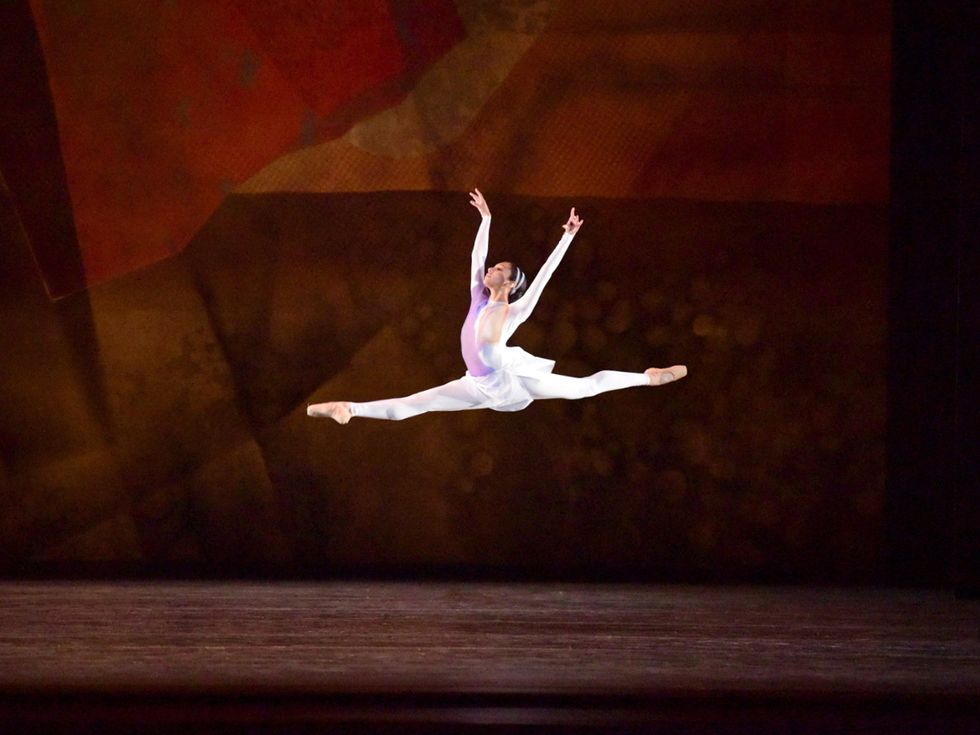

Aftereffect Gene Schiavone, Courtesy ABT

Erica Lall, American Ballet Theatre corps member

Hire Black leaders:

“Microaggressions are incredibly discouraging. During my pre-professional training, I once had a teacher walk by me at barre and say, ‘I just can’t look at that anymore.’ We can’t address these issues because our voices are constantly silenced, the threat of termination looms or there is just a transfer of blame by the people in charge. We need more Black people in power for true equality to exist.”

Promote all your artists:

“It feels like there is a mentality in ballet where there cannot be too many Black artists succeeding in one company simultaneously. But promoting and supporting all the dancers of color is literally better for everyone.”

Taylor Stanley, New York City Ballet principal

Listen and digest:

“During my training I was often the only male and one of few dancers of color. I felt recognized and celebrated for my talent while my biracial identity was being simultaneously suppressed. Your perception of yourself begins to shift. It is important for schools and companies to honestly and authentically bring dancers of different experiences and identities to the forefront. There needs to be intention and purpose behind the daily interactions between administrators and educators and their dancers. Any non–person-of-color needs to understand that, within these conversations, our pain is not a result of their actions. Reconfigure your brain to not be defensive—just show up, listen, have sensitivity and digest the information. Allow time for Black artists to express how they feel about the work being done and make space on the other side to receive those feelings.”

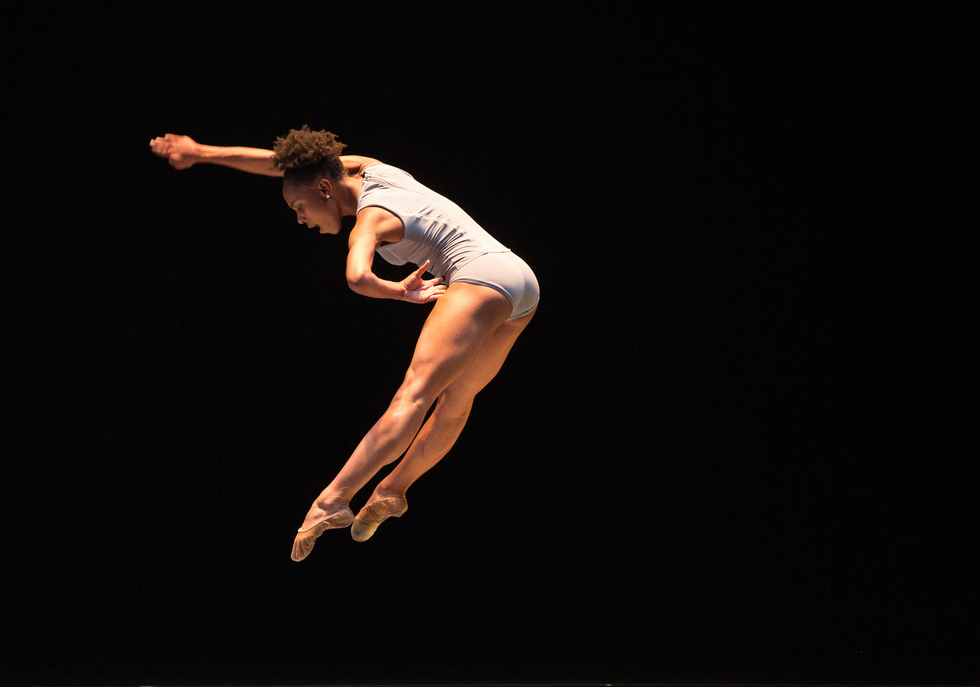

Napoli Emma Kauldhar, Courtesy Trockadero

Boysie DiKobe, Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo dancer

Train all body types:

“I destroyed my body to adhere to the unrealistic standards of executing technique based on a certain anatomy. You can make great dancers without damaging them. Educators need to learn about the limitations and capabilities of all body types. The body is just a skeleton to build technique, and should be viewed as equal beyond the color of its skin.”

Stop pancaking skin:

“Pancaking yourself in roles for Giselle and Swan Lake is highly problematic. The characters are nonexistent. I just want to see talent and hard work onstage. Yes, it’s possible to have someone in brown tights and pointe shoes onstage be the lead.”

Lindsey Donnell, Dance Theatre of Harlem

Go there:

“We need to have more open and honest conversations. Politically correct and coded language hinders real progress.”

Recruit those without resources:

“We need to broaden our definition of diversity. Race and skin tone isn’t the only thing that needs to change—we also need to address financial opportunity. The ballet industry caters to the wealthy, from auditions to training to being a professional.”

Alexandra Newkirk, freelance artist

Hire with integrity:

“Honesty would be a great start for changing recruitment. Saying things like ‘We just don’t have a spot for you,’ ‘You’re not a good fit’ or ‘Our diversity quota is filled’ is less discouraging than making it all the way through an audition and hearing nothing. I feel like I have to fit a mold, or replace another Black girl just to be seen. When I see just one other Black dancer at my audition, I know it’s either going to be her or me. She is the only one I am competing with because we will never be compared to the many white dancers in the room. This needs to change.”

Kyle Davis, Tanzcompany Innsbruck dancer

Eliminate typecasting:

“Destroy the stereotype of the Black body. Directors need to stop associating body types with roles. Audiences and artistic directors would be surprised by what a ‘different body’ can bring to the table, and it would simultaneously change their perception of what they think ballet should look like.”

Jenelle Figgins, Aspen Santa Fe Ballet dancer and activist

Make ballet for everyone:

“Because of ballet’s elitism, Black dancers cannot see themselves being part of it. Ballet is still on reserve for the rich, but it should be for everyone.”

Honor Black artistry:

“There’s no appreciation for the contributions and legacy of Black artistry until they’re on a white body, and then they are erased. We see this when dancers’ choreography is not credited, or it becomes restricted and then placed on a white principal dancer.”

Appreciate the challenge:

“Acknowledge the dual existence of your Black dancers. We are swallowing to survive and presenting to thrive. When we report micro-aggressions or instances of discrimination, we are gaslit and not heard. The trauma of being in a white space becomes expected.”