Don't Call It "Backup" Dance

The term “backup dancer” might bring to mind the army of women on Beyoncé’s Formation tour, or the men who didn’t miss a beat during Mariah Carey’s recent New Year’s Eve performance, maintaining flawless unison as she dealt with technical difficulties. Choreography for concerts tends to be almost aggressively slick and synchronized, a sea of dancers serving to multiply the image of the star.

Jim Lafferty

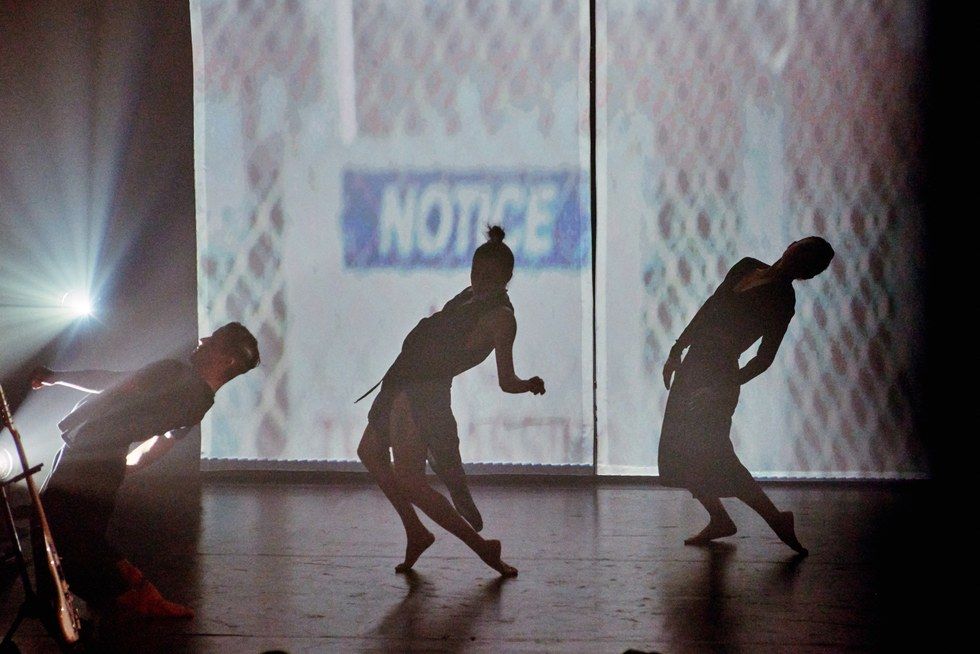

But when it comes to making dance for the music industry’s stages, the Japanese-born, Brooklyn-based choreographer Juri Onuki is in a league of her own. Last fall at Terminal 5 in New York, Onuki, 34, was one of three dancers accompanying Dev Hynes (also known as Blood Orange) during the tour of his new album Freetown Sound.

The choreography, which Onuki whipped up in just a few rehearsals, ranged from fluid pop-and-locking to angular balances you might find in a Merce Cunningham technique class.

Jim Lafferty

“It’s the most mixed bag of choreographic styles I’ve ever experienced in one show,” says dancer Jordan Isadore, whose free-spirited duet with Hynes, in which Isadore lifted and spun the singer, was a high point of the concert. “She’s totally into old-school hip-hop—not trying to perfect it, just capturing the ideas—mixed with New-York-City-Ballet-Justin-Peck-roll-off-canon feelings, mixed with West Side Story. It’s constantly refreshing itself.”

Onuki has worked with Hynes—who is himself an excellent, if not formally trained, dancer—on several music videos, both as a choreographer and in the more collaborative role of movement consultant. Her inclusive taste, the sense that no juxtaposition is too odd, pairs well with his own hard-to-classify style.

Jim Lafferty

The Freetown Sound tour was Onuki’s first time choreographing a live show for venues as large as the Theatre at Ace Hotel in Los Angeles (capacity 1,600) and Terminal 5 (capacity 3,000). That scale presented new challenges, like creating movement that would read clearly on stages full of sound equipment, for audiences sitting far away or standing near the front, and managing her own nerves while dancing for big crowds.

“I had to tell my dancers to calm me down, because I got so nervous,” she says. “I totally trust everybody else but myself.”

Onuki and her two dancers are better acquainted with New York City’s contemporary dance scene, where the audiences are smaller, the music not as loud, the lights less bright.

“What’s so different is that people are screaming at the top of their lungs,” dancer Eloise DeLuca says of performing with Hynes. “So you get that adrenaline rush, and sometimes it’s too much; we all make our mistakes onstage. But the exciting thing is you can play it off a little better. No one’s going to remember in this context that I did two chaîné turns instead of one, or that I was shaky on my leg.”

Jim Lafferty

While the audience size could be nerve-racking, DeLuca enjoyed breaking out of “I’m a modern dancer” mode, she says, and exploring a “more human” side of performing, which came in part from dancing to live music.

“You can really get lost in it,” she says. “It’s purely fun. You look out and see a sea of people with iPhones staring at you, and it kind of changes your perspective. You realize that you’re part of something much bigger going on all around you.”

Photo by Jim Lafferty