A Fresh Cup of Tea: How to Make Nutcracker More Inclusive

It’s Nutcracker time again: the season of sweet delights and a sparkling good time—if we’re able to ignore the sour taste left behind by the outdated racial stereotypes so often portrayed in the second act.

In 2017, as a result of a growing list of letters from audience members, to New York City Ballet’s ballet master in chief Peter Martins reached out to us asking for assistance on how to modify the elements of Chinese caricature in George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker. Following that conversation, we founded the Final Bow for Yellowface pledge that states, “I love ballet as an art form, and acknowledge that to achieve a diversity amongst our artists, audiences, donors, students, volunteers, and staff, I am committed to eliminating outdated and offensive stereotypes of Asians (Yellowface) on our stages.”

Our pledge served to consolidate many conversations already happening on the ground across the country around how to represent Asians in The Nutcracker and other classical works. We are thrilled to have the support of almost every artistic leader from the major American ballet companies.

Since our Yellowface pledge went public last year, we’ve received hundreds of letters from Asian-American students, parents, teachers, and both professional and retired dancers talking about how caricatured “Chinese” dances in The Nutcracker have always bothered them. The most common question we’ve received is, How do we start this dialogue at our own studio/company to make our Nutcracker more inclusive?

We’ve discovered three areas in the divertissement where creative questioning can help productions become more respectful to Chinese culture, while remaining faithful to the artistic visions of the past.

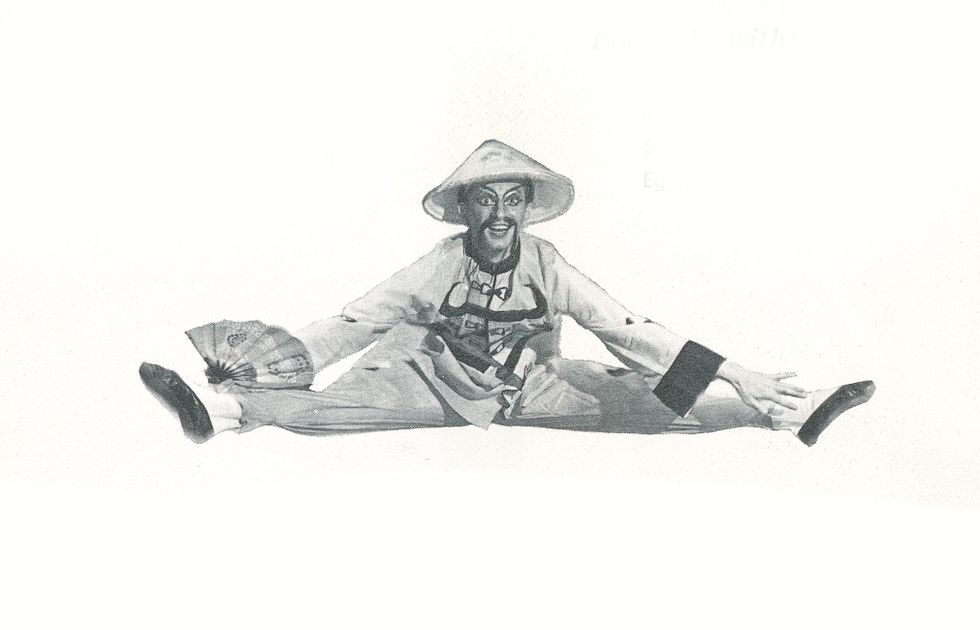

Makeup and Casting: Why the Yellowface?

In 2019, do we really need makeup that exaggerates Asian racial features for audiences to get that this dance is “Chinese”? An easy option to avoid caricature is to keep makeup designs clean and simple, bringing out colors from the costume and accentuating the natural features of the dancer regardless of their race.

It seems reasonable to assert that an audience in 2019 doesn’t need painted elongated eyes or a Fu Manchu mustache to get that this divertissement is “Chinese.”

If you want to lean into Chinese culture, consider borrowing a design from Peking Opera, a rich theatrical tradition in China where different colors in the masks represent different character traits. Ballet West’s current version of the divertissement features a Peking Opera-inspired warrior battling a playful Chinese dragon.

Directors should also not feed the pressure to cast Asian (or Asian-passing) dancers in the “Chinese” divertissement just because they are Asian. Regardless of race, cast the dancer who performs the choreography the best, and most embodies the spirit of the dance. Sometimes that will be an Asian dancer, and that’s okay too!

Choreography: What’s with “The Fingers”?

Certain physical caricatures of Asians by Westerners have persisted across film, vaudeville and the performing arts throughout history. When translated to the stage, the Chinese tradition of bound feet became small shuffling steps, while the humble bow gesture became an exaggerated head bobbing, and in classical ballet, the two raised index fingers.

At one time, these movements may have been attempts at imagined Chinese character dance, but they’ve warped into physical caricature meant to create a comic, simplistic or grotesque impression.

We’ve come across two theories about “the fingers.” One idea is that the gesture is based on a chopstick dance, and that the individual digits represent chopsticks. The other is that porcelain makers at the turn of the 19th century wanted to show their virtuosity as artists, and would create porcelain figurines (“China”) with the people depicted holding up individual delicate fingers, something quite hard to do.

As “Nutcracker Nation” author Jennifer Fisher wrote last year, “One of the most common of the ballet world’s efforts to signal Chinese-ness is a particular hand gesture—a sort of two-finger salute with the index digits of each hand stretched out to opposite sides like a peripheral vision test. Any Nutcracker aficionado will recognize it as ‘Chinese,’ but as a dance scholar, I can tell you the gesture does not exist in any version of traditional dance in China…The finger-pointing is mostly an example of heedless insensitivity to stereotyping.”

If your production features unnecessarily caricatured mannerisms, consider going back to the music to find inspiration. Is anything truly lost if the hand gestures are altered slightly or a little bit of head bobbing is removed? What are other spritely and playful ballet steps are suggested by the different layers of music that can be celebratory for everyone?

Costuming: How to Represent “Chinese”

A few different wardrobe approaches are possible. You can lean in and make costuming historically accurate, and be inspired by Chinese fashion. However, bear in mind that while a Chinese person depicted as a railroad worker or rice farmer (“chinaman” or “coolie”) might be historically accurate, it is a caricature that Asian people are trying to move away from. Could the same choreography be performed by Chinese princes and princesses? What about leaning into the confection angle and have dancing Fortune Cookies?

You can also lean out of anything Chinese whatsoever; the National Ballet of Canada’s production choreographed by James Kuldelka to the “Chinese” divertissement features dancing chefs chasing a turkey.

Animals are also a lot of fun and a great combo approach. Pacific Northwest Ballet’s Arabian variation features George Balanchine’s choreography but is danced by a peacock instead of a harem dancer. A lot of successful “Chinese” divertissements we’ve seen include dragons, pandas, Chinese lions and other animals associated with Chinese culture.

Pruning to Preserve

Ultimately we want to make sure the ballet community actively engages in these sometimes challenging conversations surrounding race and representation by continuing to examine the choices we present on stage, in order to better preserve these pieces as living works of art. This process of understanding the history of both the ballet itself, as well the complex histories of different racial groups in our communities, is the key to making both the creative work and our community overall more inclusive.

We like to think of the true ballet masterpieces like Japanese bonsai trees; if we want them to live and keep their shape, they sometimes require a little delicate pruning. Changing a little bit of head bobbing to avoid perpetuating Chinese stereotypes does go a long way with audiences; modifying make-up just a little bit to avoid caricature doesn’t make the work any less charming. Small updates to refresh portrayals of race ensure that classic works like The Nutcracker stay alive and become bigger than what their creators intended.