From Urban Bush Women to Robots: Meet Grisha Coleman

I first ran into Grisha Coleman in Dayton, Ohio, some 20 years ago, when she was touring with the Urban Bush Women. Even within a company of brilliant dancers, she was a technically inimitable, radiant performer.

Since her time at UBW, her cerebral, dancerly ferocity (and choreographic kick-assery) landed her a Harvard Radcliffe Institute fellowship and an associate professorship of movement, computation and digital media at Arizona State University. Her expertise spans choreo-robotics, computation and somatics, resulting in genre-exploding performances and a singular pedagogic approach. I spoke with Coleman about her work and the future of dance in the emerging, post–COVID-19 moment.

What is your dance history?

My adult art life started as a member of the Urban Bush Women. I did that for four years, which was life-altering and specific. There was no other postmodern Black women’s dance company in the U.S. at the time. I was experiencing what it meant to make work in process with Black artists at the peak of their powers—it was access to an unbelievable dynamic hurricane of Black artistry.

Then I created my own ‘”group” with my close friends Viola [Sheely], Johnathan [Stone], David [Thomson] called Hot Mouth. We were all from the dance world, but the choreography was coming out as music! I began to compose and to lead. I made my first solo piece, Black Alice, on commission from Mark Russell at PS 122, and the second half of the evening was Hot Mouth, and we received our first review, from Deborah Jowitt. That was a turning point. Hot Mouth became popular; we had chances to bring it to Broadway or the West End—it was nuts—but I was not feeling it (much to the chagrin of my dad). I did wish we had gone on Letterman, though!

I went to get a master’s degree in music composition from California Institute of the Arts. The dancers thought I was a musician; the musicians thought I was a dancer. CalArts opened up the use and legacies of electronics in music and art making, and somehow California created open spaces in terms of cross-collaboration with the sciences.

After that, I got into Carnegie Mellon as a fellow at the STUDIO for Creative Inquiry. That continued this expansion—the position required liaising with human/computer design, robotics, which informed my project echo::system. In a way, that’s when I stopped being a dancer, or, more specifically, I had a dancer’s mind doing these other things, synthesizing through the body, as we tend to do.

How did you make the decisions that resulted in these career moves?

At the time, for me, the concept was not about career. I was deeply webbed in art practice and in that networked New York community. It was how we were collaborating, how electric and live it was, this art making and living. I didn’t care if it was right. I didn’t care if I didn’t have any money. I was motivated by what interested me. The basic thing is, I could move, and so I did. I moved towards my interests because I didn’t have fear of immediate starvation or imminent homelessness. The community of folk supported each other. I understood—I understand—myself as part of a lineage, as part of a movement.

Now I am an associate professor of movement, computation and digital media at Arizona State University…how did I get here?! It was just as much about constraints and blockages as it was about “decisions.” For example, in most music schools, the idea of a conservatory is linked to concepts of virtuosity inside a European Western classical music tradition. CalArts has a history of electronic music, world music, contemporary jazz—experimentation. I was inspired by this, and it wasn’t just music I was engaged with there. It was design, animation—kids doing insane, non-Disney stuff.

In the School of Arts, Media and Engineering, where I am, I was hired, but I didn’t have a computer science degree. The amazing director, Thanassis Rikakis said, Come on! You teach our motion-capture class! And so, I learned about that. And then I co-taught Understanding Activity with my engineering colleague. And I designed Hybrid Action: Physical Intelligence in Digital Culture and then later on Somatic Prototyping.

For a long time, I’d build my classes around automata, cellular automata and flocking. So I would do flocking constantly, physically! Those kids hated me, but I was like, “We’re gonna do this.” It covered systems thinking and it covered computation—but it’s all pure movement studies, every improvisor knows this: orientation, interaction, responsivity, timing, everything. I felt the students had to feel it.

Then fast-forward to this semester; co-teaching “Expressive Robotics” with a sculptor, and I co-designed a course for COVID (just kidding) called Sociotechnical Futures: What Are We Building? Culture, Methods and Alternative Visions for a Sociotechnical Future.

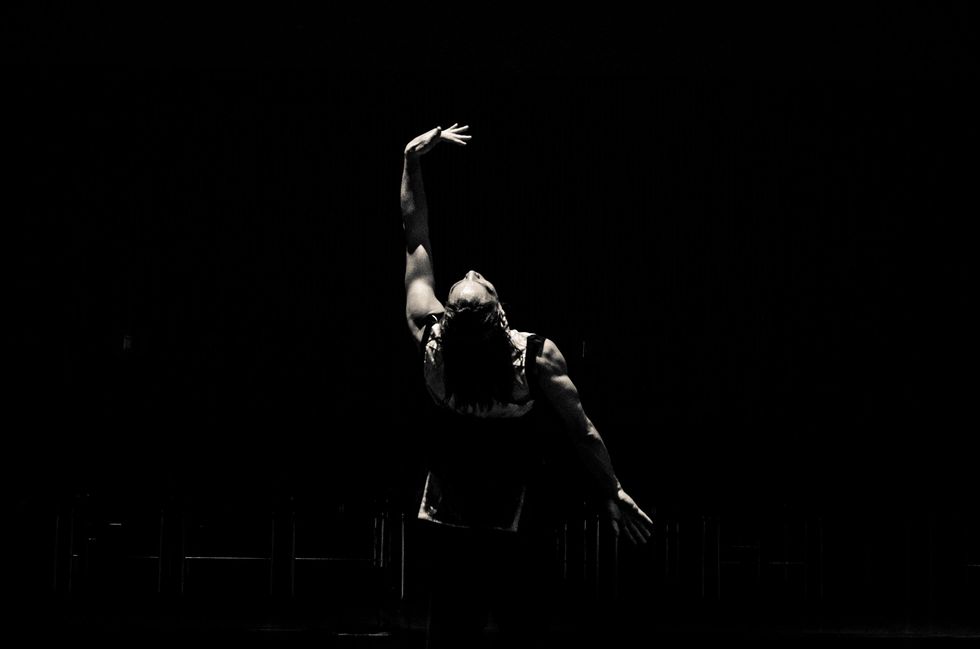

Robbie Sweeny, Courtesy Coleman

How does your expertise feature in your interdisciplinary practice?

Movement lends itself to interdisciplinarity. Hybridity is a natural state for me—to be singular takes a ton of work!

I want to include human movement in the critical conversations around environmental degradation, around social justice, around technology and inequality. It’s a reach, across my fields. I find many engineers don’t think it’s important. They tend not to consider how we move, let alone how to make a robot move. But they know the benefits of having artists on the team—because they result in better, more interesting, more robust, more complex projects.

What would conversations around polyrhythm and improvisation in the context of robotics look like? I did this work with a PhD student: He built a robotic djembe and I choreographed to it—but we [the robot-drum and I] were both improvising. It was cool and produced new scholarship—certainly considering more than just whether or not the thing worked.

Can you tell me about the Radcliffe project?

The project at Radcliffe is called the Movement Undercommons (Technology as Resistance/Future Archive), or something like that. We each have our own movement fingerprint, and you can be recognized with a very small amount of data. There’s much good and critical work around facial recognition, groups addressing all sorts of critical issues—I am part of a consortium of African diasporic Black scholars called AI 4 Afrika. But this whole-body motion capture is something else.

This project looks to create a vernacular movement lexicon—to take data governance and embodiment and social justice conversations to another level. Movement itself is the last bastion of commodification. It’s a different code, a different mode of exchange. Choreography studies this. Movement artists study this.