Three Choreographers on Making Memoiristic and Biographical Works

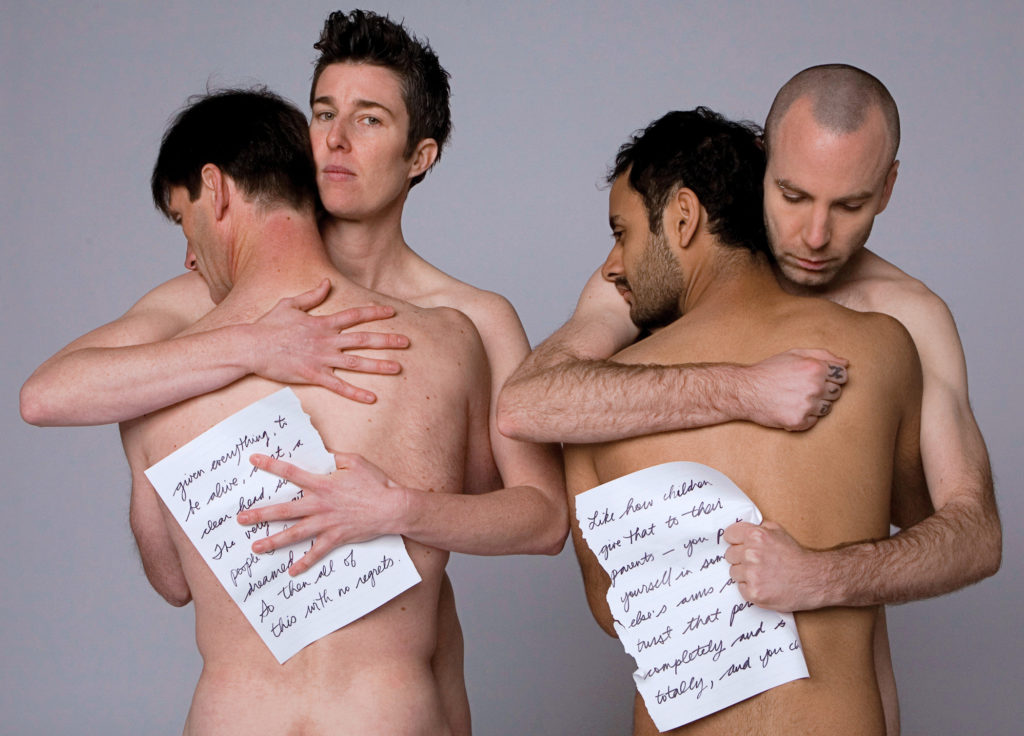

For many choreographers, starting a new piece begins with noodling around in the studio. But for those who make dance works rooted in biography or memoir, it can begin at a writing desk, in a hushed library or in front of a recording device. The last was the case for dancemaker Sean Dorsey. To build his 2015 The Missing Generation, the director of Sean Dorsey Dance spent a year traveling around the country conducting oral-history interviews with longtime survivors of the early AIDS epidemic. “I did not set out to, but I recorded 75 hours of histories because I just kept meeting the most amazing people, and the stories were so compelling,” he says. Only once Dorsey had distilled the interviews into a nearly finished sound score did he bring dancers into the studio to create movement.

Whether you’re mining your own life or the lives of others to build a dance piece, the process is rife with questions: How do you pay tribute to others’ pasts without exploiting them? How do you turn writing into a dance? How do you mine your own trauma without re-experiencing it? Dance Magazine talked to Dorsey and two other choreographers making biographical and memoiristic work to hear about their unique processes.

Excavating the Personal Story

Choreographer Jack Ferver began building Is Global Warming Camp? and other forms of theatrical distance for the end of the world as part of their daily writing practice. Prior to its premiere at MASS MoCA in September, they spent four weeks in residency throughout the summer and devoted time to slashing through the text, editing it down to a length that works for a stage piece. “In terms of my process, the text comes first, and then the dance,” explains Ferver. “I try to be really pure with each form first, so when I’m making movement I won’t even think about what I’ve written, just what feelings are arising.” Like Is Global Warming Camp?, Ferver’s previous full-length piece, Everything is Imaginable, blends personal experiences of queer trauma and child abuse with elements of research and fiction. In Everything is Imaginable, Ferver speaks aloud a long monologue while performing a dance solo. To create the movement, Ferver focused on crafting an abstract choreographic sequence that was as long as the monologue, without thinking about the text itself. “Then in my mind I just pressed ‘Play’ at the same time,” they say.

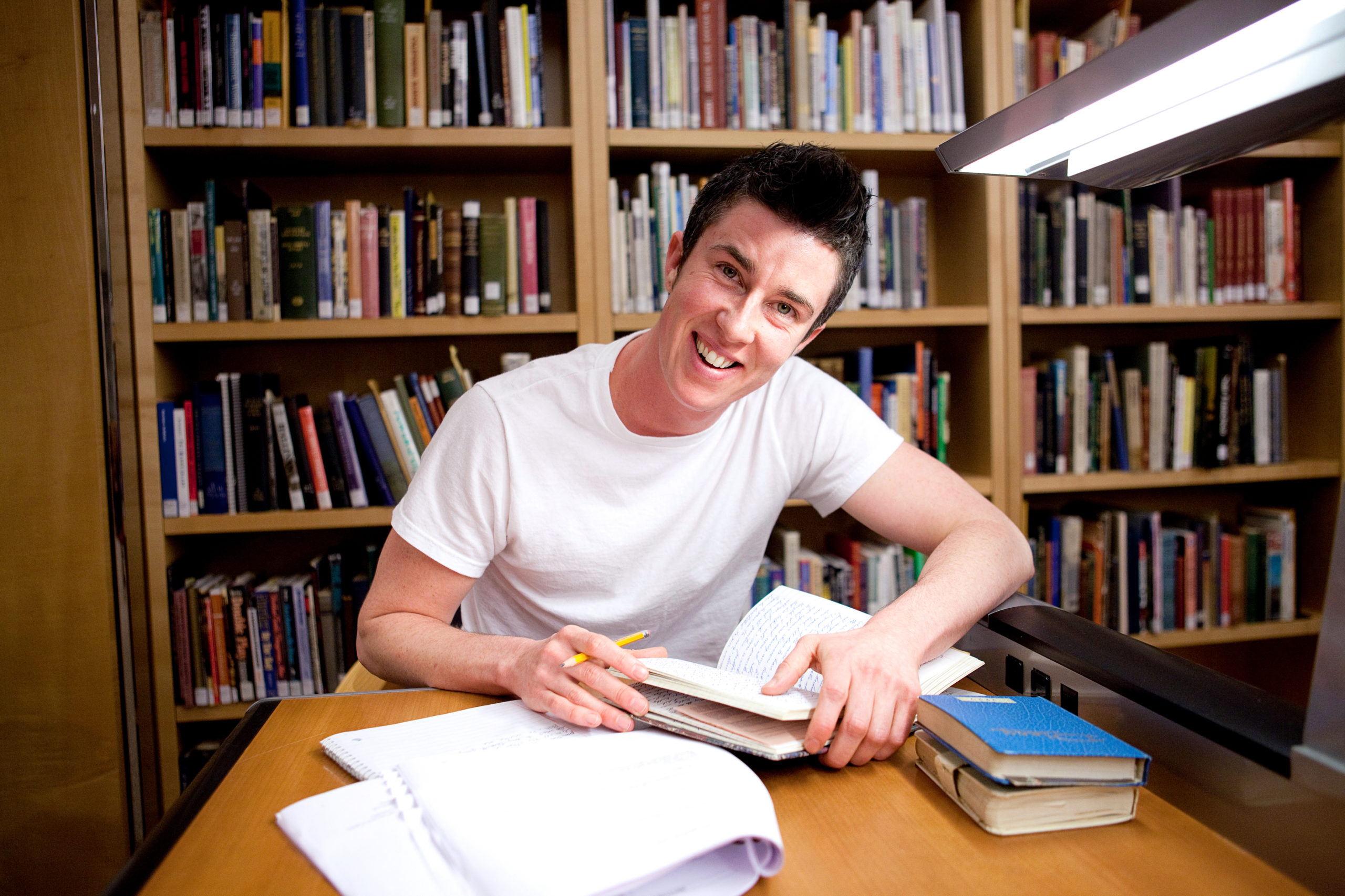

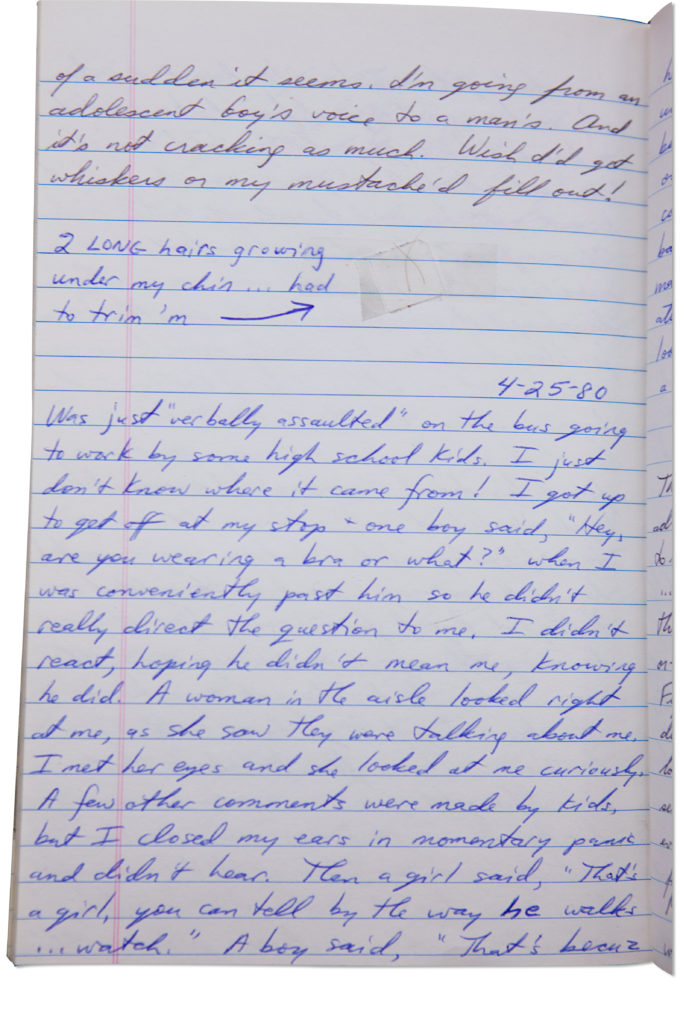

Though much of Dorsey’s work centers the lives of others, he often incorporates his own personal history. And, like Ferver, for Dorsey that starts with writing. Dorsey used to see his passion for dancing and writing as parallel tracks; it wasn’t until he was in his 20s that he started melding the two. “It was simultaneous to me as a trans person becoming increasingly aware of never seeing myself anywhere in the modern-dance world,” he says. “So it was in that bringing together of autobiography and movement that I was able to declare myself worthy of being a part of that world and insert myself creatively.” Dorsey tends to record himself reading his writing and layer it over music, then have his dancers listen to the score and build a movement vocabulary together. In his 2009 Uncovered: The Diary Project, diary entries by transgender and queer people are sandwiched between entries from Dorsey’s own childhood diary, a Norman Rockwell–illustrated journal with a lock and key titled Diary for a Young Girl. Dorsey explains, “That had sparked my curiosity about memoir and diary and journals as revelations of self.”

Sharing Others’ Stories

For her last two full-length works, choreographer Marjani Forté-Saunders has followed what she calls “a biographic line of inquiry.” The first, titled Memoirs of a…Unicorn, premiered in 2018 and explores Forté-Saunders’ father’s life. The second, PROPHET: The Order of the Lyricist, is a collaboration with her husband, Everett Saunders, and tracks his journey as a hip-hop emcee and lyricist. For both pieces she’s contextualized her subjects’ stories through research, and fleshes them out through interviews. “With my dad, it was a real intentional interview process, but with Everett, sometimes he’ll be telling a story and I’ll say ‘Stop, stop,’ and pull out my phone,” says Forté-Saunders, who adds that her phone is full of both voice memos and notes she jots down while commuting on the subway. Forté-Saunders credits her ability to draw out these stories partly to her time as a member of Urban Bush Women and the company’s work with Junebug Productions, a theater troupe focused on confronting racial inequality through telling Black stories.

While Forté-Saunders dives deep into one subject’s life story, Dorsey has tasked himself with collecting dozens at a time. He talked to friends who are historians, filmmakers and audio engineers to learn how to conduct formal oral histories for both The Missing Generation and his 2012 The Secret History of Love. “Having heart-centered conversations was not a new skill set for me, but structuring an oral-history set of interview questions and figuring out the legal language of release forms was new,” reflects Dorsey. He mixes the recordings he collects to create his pieces’ scores, and hopes to eventually share them as an archive in their own right, so it’s important that he collect clean sound. Over time he’s mastered tricks of the trade, like asking subjects to remove jangly earrings before recording, and resting his microphones on soft towels.

Interviewing is a great tool when subjects are living, but archives can be priceless when looking at subjects who are deceased. For Uncovered: The Diary Project, Dorsey spent years exploring transgender activist Lou Sullivan’s collection, housed in San Francisco’s GLBT Historical Society. Ferver had a similar experience when completing a fellowship at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts’ AIDS Oral History Project. Ferver and their partner Jeremy Jacob created Nowhere Apparent, a dance and spoken-word piece made in response to their research in the collection.

Why Dance?

Memoir and biography are thriving literary genres. So why are artists compelled to intermingle text with movement rather than let their writing stand alone? For Forté-Saunders, storytelling through movement grounds her. “The movement material always has a root, so I never get lost in generating movement,” she says. For Ferver, it’s about the physicality. “I think I absolutely would have stopped making live work if I hadn’t had such cathartic experiences watching it. It bypasses a lot of my criticality.” Dorsey agrees: “When these voices and experiences get shared onstage by a dancing body, there’s this immediate visceral connection with the audience. There’s a way when it’s done well that the embodiment, whether abstract or literal, brings these stories alive for people—and keeps them alive.”

Self-Care

Diving into the difficult parts of our lives, and the lives of others, can bring old trauma back up to the surface or create new vicarious trauma. Dance/movement therapist Erica Hornthal, founder of Chicago Dance Therapy and author of the new book Body Aware, offers tips on maintaining mental health while creating biographical or memoiristic dance work.

- Seek a support system: This might mean a strong network of friends to check in with, or a mental health professional. “When we move, we feel more. So even if we think we’ve processed trauma already, when we express it through the body, it can surprise us,” says Hornthal. “It can almost cause us to re-experience some of those traumas again.”

- Create a ritual: Hornthal recommends creating an anchor to connect back to the present when things get tough. “That can be breath, gently shaking out the body, a gentle self-hug, a hot cup of tea in the afternoon. Something that sensationally connects us to the moment.” Hornthal also suggests trying a tangible somatic tool called a “5-4-3-2-1” practice: “Stop and list five things you can see, four things you can hear, three things you can touch, two things you can smell and one thing you can taste.”

- Pre-test/post-test: “Before a choreographer is engaging in this work, do a self-check-in to see how you’re feeling right now,” says Hornthal. “At the end of the day, ask yourself what’s coming up for you. How is your body different than it was at the start of the day? Is there anything you need to release or vent or physically express?”

- Set clear boundaries: Presenting highly personal work to audiences and critics can put choreographers in an extremely vulnerable position. Hornthal recommends setting limits around reviews and feedback. “If you’re doing this kind of work, it’s not necessarily for acclaim,” she says. “Remember that this is how you chose to express yourself; remain true to your intention.” She recommends having a trusted colleague or friend who can read feedback, and filter out what might be hard to hear. “If we’re already operating at a very high stress level, the last thing we want to do is to continue to throw things in that are just going to clog the system.”