Creating New Futures Is Reimagining the Relationship Between Artists and Presenters

At the start of the pandemic, many artists felt as though a rug—one that was awfully thin to begin with—was pulled from underneath them. Performances were rescheduled, and then, in many cases, canceled altogether. Freelancers and independent artists, who often invest significant personal funds in their own work, were hit particularly hard.

Several artists went public in their fights to be paid for canceled gigs, prompting conversations about how things could be different. A group of dancemakers, presenters and administrators got to work, eventually releasing a document called “Creating New Futures: Working Guidelines for Ethics & Equity in Presenting Dance & Performance.” It was part manifesto and part testimony, authored by 10 people and featuring personal stories from dozens of artists. The work was supported by the MAP Fund and the National Performance Network, and included contributions from programmers at venues including Dance Place, The Chocolate Factory and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. It was presented in a virtual event hosted by Abrons Arts Center in May 2020.

That was phase one.

During the Zoom presentation, rapid-fire conversations erupted in the chat and, later, in a Facebook group. With new participants on board and working groups created to address different issues, Creating New Futures forged ahead into phase two, eventually becoming the beneficiary of a $50,000 grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Many of the changes conceptualized in phase one are already materializing.

However, as the work continues and the group expands, the people behind CNF have been reminded that it’s not just the relationships between artists and institutions that need mending—it’s also the relationships among artists themselves.

A New Approach to Contracts

Among the presenters taking active steps toward change is Dance Place in Washington, DC. Associate curator and producer Sarah Greenbaum and director of production Ben Levine are both part of the CNF Contracts Working Group. Guided by feedback from the group, they are overhauling Dance Place’s presentation contract, in the hopes that it will serve as a useful reference for presenters.

“Looking at our old contract, we see how totally insufficient it was,” says Levine. Among the changes are contingency plans: The contract outlines how an event could be adapted to be physically distant or held virtually, if that’s the right fit for the project, and if that isn’t possible, postponed. Cancellation is a last resort. Rather than being paid a lump sum once the gig is complete, as is common at most venues, artists will be paid according to a clear fee schedule. They receive their first payment upon signing the contract and additional payments at other benchmarks.

Dance Place has also begun conducting contract walkthroughs with every artist, to ensure all elements of the contract are understood by all parties. “We’re shifting away from the mindset of the performance as a product that we’re purchasing to thinking of the performance engagement as a relationship that we’re embarking on over a period of time,” says Greenbaum.

SoleDefined in Zaz at Dance Place

Jonathan Hsu, Courtesy Dance Place

It’s precisely this attitude that more venues need to cultivate, says Sandy Garcia, director of booking at the artist services organization Pentacle. “We surveyed a group of presenting organizations about what they thought happened when force majeure was invoked, and across the board, they thought it means that the agreement is terminated and everyone walks away. But when we conversed with a lawyer about that, he said legally you could do that. But is that a wise business decision for the sustainability of your field? And the truth is that it’s not,” says Garcia.

Widespread cancellations led artists to feel taken advantage of. By adopting contingency plans and changing payment structures, she says, institutions can earn back artists’ trust.

However, these changes will require funders to adapt as well, dispensing more money up front rather than waiting until a project is complete. “The next step of the conversation is saying to the ones who have the money: This is how we need to operate to make things sustainable. What can you do to change the way funds are distributed to make this possible?” says Garcia.

Intersectional Riders

Creating New Futures was never just about cancellations—it always sought to address broader inequities and power imbalances. One of the ideas to arise from the initial presentation was that of an intersectional rider, language that artists could include as a clause in their contracts or in a complementary document asking presenters to ensure equity and access for artists and audiences. The idea was based on practices that some in the CNF community were already employing, says Michael Sakamoto, an interdisciplinary artist and the interim director of programming at the UMass Amherst Fine Arts Center and director of its Asian and Asian American Arts & Culture Program.

For example, dancemaker Emily Johnson has a decolonization rider in her contract, requiring, among other things, an Indigenous land acknowledgement in all promotion and presentation of her work. Alice Sheppard, of Kinetic Light, requires accessibility measures in all of the company’s work, from community outreach to marketing to the performance venues. These can include American Sign Language interpretation, audio description, live-caption services, front-of-house staff training and facilities accessible to wheelchair users. Choreographer Sean Dorsey requires gender-inclusive practices, such as all-gender restrooms.

Combining these and other equity concerns, the Intersectional Rider Working Group is drafting language it hopes will become standard in the industry. Sakamoto says they’ve also come to see the project as more than just a legal document. “No document we come up with is going to completely cover any one area of race, or gender, or decolonization, or accessibility. But we hope it can be a useful container, or template, which artists, and presenters, and funders and others can work from to create concrete commitments to inclusivity,” says Sakamoto.

Michael Cohen, Courtesy Sakamoto

Public Accountability

CNF hopes the guidelines it compiles could inform a public ethics pledge that would be collectively written with arts workers, presenters and organizations across the field. “We need to take some of this labor off of arts workers,” says Johnson. “Yes, that means presenters need to do the work and arts organizations need to do the work. But audiences and the broader public can become part of this change too,” she says. Making the pledge public means audiences can be part of keeping institutions accountable.

“An ethics pledge could also be something that funders could then utilize to say, ‘If you haven’t signed on to this pledge, you cannot receive funding,’ ” adds choreographer Yanira Castro. Johnson and Castro are in early conversations with various organizations about potentially developing an ethics council.

Change From Within

Dancemaker April Biggs joined phase two of CNF because she felt that disability was largely left out of the phase one document. She became a founding member of the Disability+ Working Group, which initially focused on compiling testimony from disabled and chronically ill dancers about their experiences in dance and how the field could become more accessible, and then recognized the need to begin by improving practices within CNF itself. These include features such as live captions and ASL interpretation for meetings, but Biggs says accessibility goes beyond that.

“For example, we requested that a week is given for responses to emails, which really has a ripple effect through the whole community. It changes how we all communicate with each other and how we regard time. That’s an example of how a lot of the practices around accessibility are often very helpful to people who don’t identify as disabled,” she says.

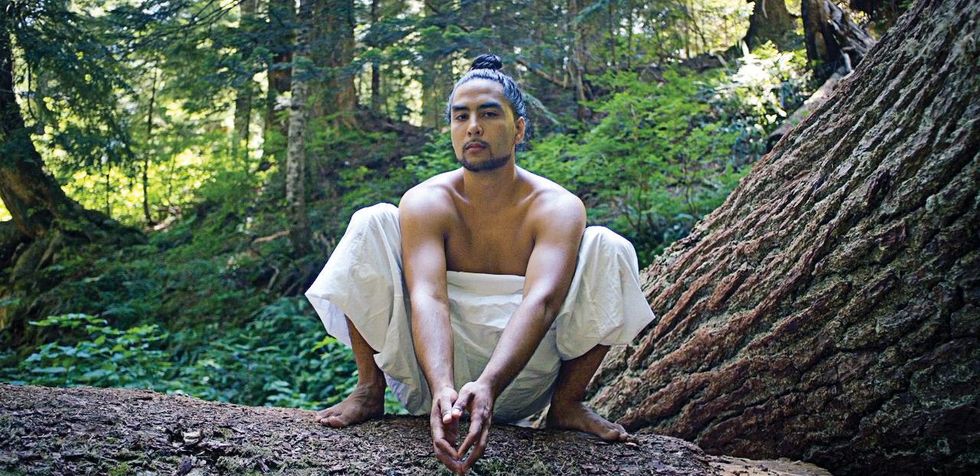

Multidisciplinary artist Dakota Camacho, a member of the Black and Native Survivors Working Group, says that when the work of phase one got noticed by influential institutions, it brought in a flood of new people, many of them white.

Futsum Tsegai, Courtesy Camacho

“White folks were dominating the space, I think for the most part unconsciously. And that was impacting the way, or whether or not, people of the global majority showed up,” says Camacho. As a result, CNF has taken time to pause and reset, and its white members are working among themselves to address the way racism was being enacted within the organization. That process is ongoing.

“The cultural shift starts with each and every one of us deciding to become aware of the places where we’re falling short and deciding to do more work,” says Camacho. “The dynamics that exist in the performing arts industry exist because of oppression. And part of how that functions is to separate us from each other, and to keep the resources out of the communities most directly targeted by oppression, to keep the resources at the top of the pyramid. And it seems to me that in order to shift the way that these dynamics are playing out in our field, it might behoove us to build deeper and more resilient relationships with one another.”