Op-Ed: It's Time to Stop Dancing to Michael Jackson

I was on my favorite treadmill when it happened.

My best running buddy was on my left. To my right, a total stranger with whom I’d suddenly become competitive. As the 15-person group headed into a two-minute push, the instructor got hyped, and the remix blasting Rihanna’s “We Found Love” transitioned to “Smooth Criminal.”

At the first familiar beat, I felt sick. I waited for the instructor to stop circling the room and to hustle back to the iPhone dock to advance the playlist. Surely she wasn’t going to let us keep running to the beat of Michael Jackson, right?

No. Not only did she not change the song, she danced along to it. She loved it.

Maybe she didn’t notice. Maybe she hadn’t seen Leaving Neverland. Maybe she’d never even heard of it. Or, the thought I simply couldn’t fathom: Maybe she had seen it, had heard of it, and simply didn’t care.

I vaguely remember watching Michael Jackson perform at the Super Bowl Halftime Show in 1993. I was 7 at the time, and even then, I remember being creeped out by the one-gloved man on the screen. This was, of course, long before the internet, but I remember people calling him a pedophile; a creep; sick. Joking about how he “loved little boys.”

But still, I listened to his music. I performed a tap routine to “They Don’t Really Care About Us,” and who among my generation didn’t dance a lyrical number to “Heal the World” at some point?

I remember being in third or fourth grade, and my tap/ballet combo class at Miss Pam’s dance studio was set to perform our recital piece to a Michael Jackson song. At the last minute, we were told we’d be dancing to a different song. No one told us why, but I remember the moms in the lobby talking about how it was because of the accusations.

That was 1993.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

But his music was so good, and we all listened. “Man in the Mirror” was my jam on dramatic high school days, and I rocked out to “Don’t Stop Till You Get Enough” while driving to my dance competitions at 7 AM. I loved the music, even if the man behind the beat made me uncomfortable.

But I can’t do it anymore.

I spent five hours last weekend watching Leaving Neverland and Oprah’s post-show interview with Wade Robson, James Safechuck and the film’s director, Dan Reed. For five hours, I cried.

I cried watching my teenage dance idol, Wade Robson, recall moments of abuse and confusion from his past. I cried tears of horror, of shock, of sadness. When I was 16 years old, I decided I wanted to grow up and work at Dance Spirit magazine because I wanted to get to write about Wade Robson. His March 2003 cover is still hanging on my childhood bedroom wall. (DON’T TAKE IT DOWN, MOM. Not ever!)

And then I cried, scrolling Twitter, assuming I would find hoards of people like myself, who were equally horrified by the film—but instead, I found an endless scroll of defenders. People calling Wade and James liars, saying they were trying to profit off Michael Jackson because he’s dead. Fans announcing they were going to listen to more MJ than ever before.

People can debate over Leaving Neverland all they want. I believe Wade. I believe James. And I believe, so strongly, that Michael Jackson’s music has no place in fitness or dance classes. Jackson was a brilliant performer and entertainer. By those measures, he was world-class; he was the very best.

In my career as a dance writer, I’ve interviewed hundreds of dancers. And while the choreography, the costumes, and the stage makeup have changed, one thing has no doubt united generations of dancers: Michael.

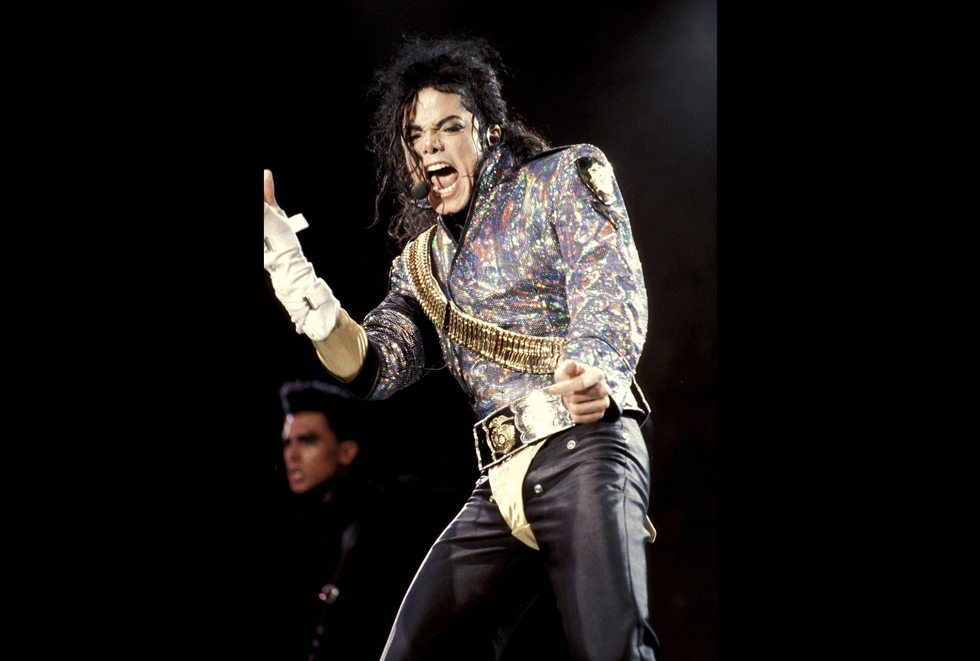

I’ve talked to pre-teen dancers whose first memories of dancing are trying to replicate that iconic moonwalk, which Jackson debuted to rabid fanfare during a performance of “Billie Jean” in 1983. (Though Jackson didn’t invent the move, he helped take it mainstream, and it became his signature.)

For dancers now in their thirties and forties, Jackson’s entire discography was the soundtrack to recitals, competitions, high school dances.

Beyond his music, Jackson could legitimately dance, and so the industry clung to him. In the span of seconds, Jackson could transition from that moonwalk into a 360-degree spin, topping it off with a toe stand that seemed to linger for days. He was smoothly robotic, precisely well-rehearsed, and impossible not to imitate. And he didn’t go it alone: Jackson was often backed by entire ensembles, like in the “Thriller” video. As the often-dubbed King of Pop, his legacy transcended the music industry.

As a human, though, he’s unforgivable. People have known that Jackson was acting inappropriately for decades. You cannot defend an adult man having behind-locked-doors sleepovers with boys as young as 7.

This morning, I talked to an internet friend who told me she “heard about all the Leaving Neverland stuff,” but that she “can’t quit her MJ.” I asked how that’s possible, and she said that, to her, the man and the music are separate. I vehemently disagree. The man is the music.