When Dance Scores Become Fine Art Prints

In the early days of the pandemic, as the full impact of lockdowns began to sink in, Kristy Edmunds, executive and artistic director of UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance, had an idea: If she couldn’t commission artists to perform, what about instead commissioning them to each create a score for a dance work?

Twenty-six artists participated, drawing, writing, collaging and/or painting submissions. Some are based on actual scores or artifacts from previous works; some are road maps to new projects; others are notes for pieces that were interrupted by COVID-19. Each is available for purchase as a limited-edition fine-art print, with sales benefitting the choreographers themselves and funding future live dance performances at CAP UCLA.

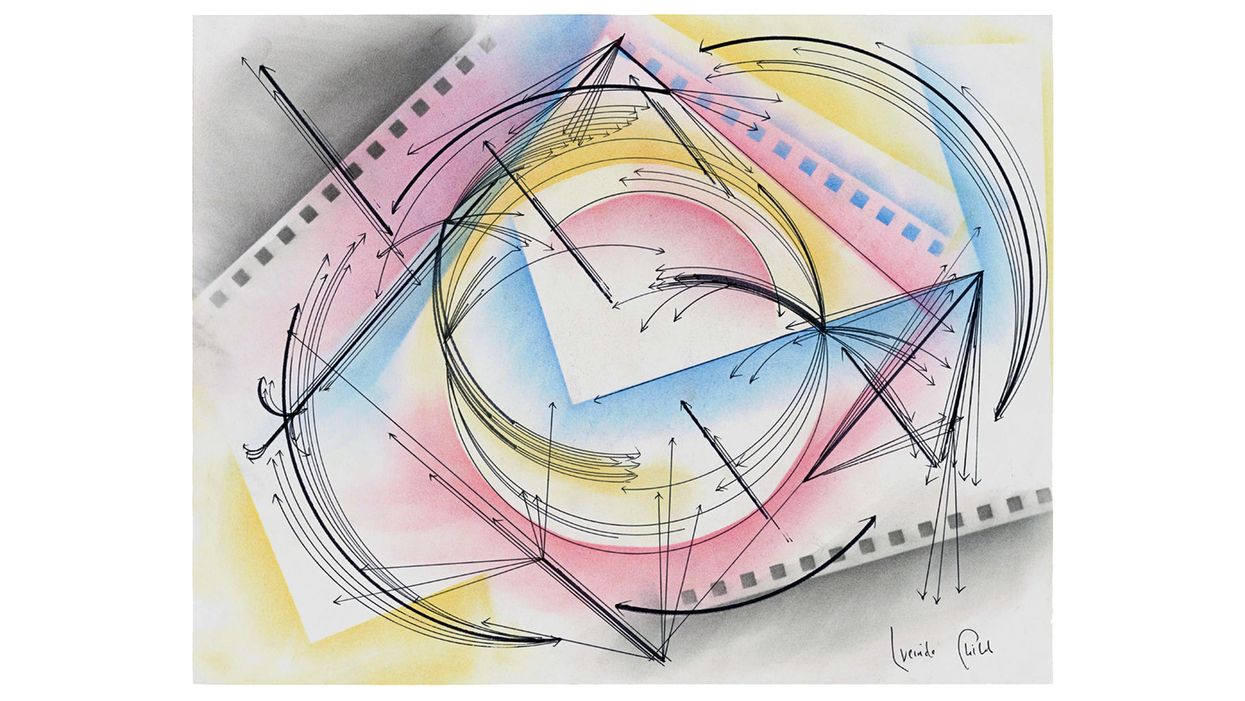

“I was beginning to organize my archival materials early in the pandemic, and this one paper landed on my floor. It was a sketch from the ’80s, of a very early work I made at PS 122 called Friends. Looking back, I came out as a lesbian shortly after that work—from my perspective, it kind of marks that, though I don’t think you’d look at the work and go, ‘Oh, a coming-out piece.’ The black lines were the spatial illustration of where the 15 performers went, what their options were. All the women—a wide net of friends I’d brought together to do this piece—had their toes on it at the start, then moved out from there.

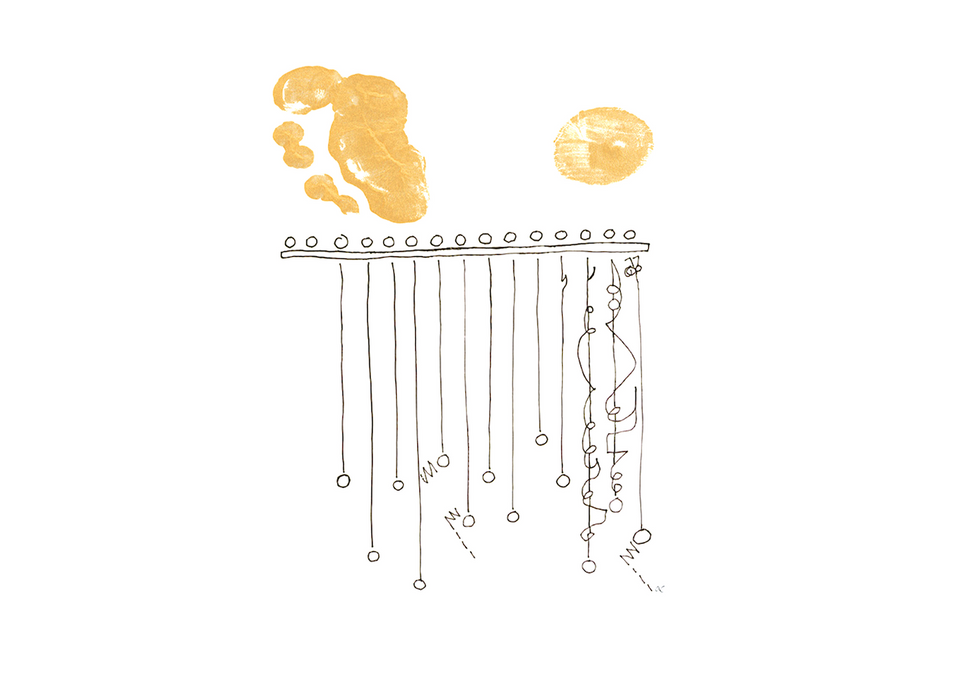

“At the same time, I started thinking about my own footprint, and how it was somehow also like standing on an edge, this precipice, while sheltering in place in L.A. So I got some gold paint for the bottom of my foot.” —Ann Carlson, interdisciplinary artist

Courtesy CAP UCLA

Courtesy CAP UCLA

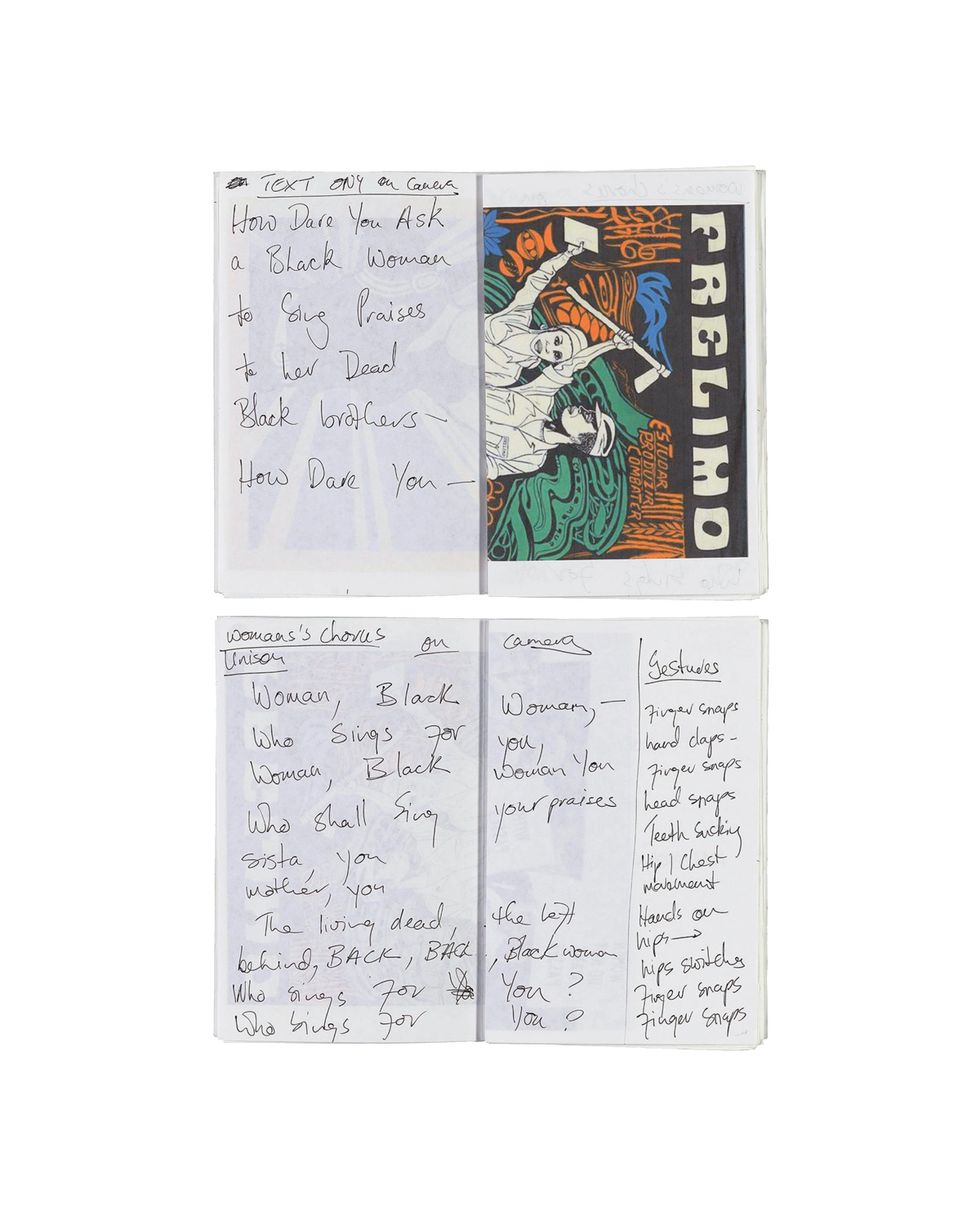

“The score was a way to think through how to do a digital work for the National Arts Festival in South Africa in a way that wasn’t just video capture. It was a manual that could be both a road map but also a thinking space.

“Putting things on paper is how I fundamentally work. Of course, the body holds ideas. If I can put words to what the body knows, it means that the body already knows it. It’s not the other way around for me.” —nora chipaumire, contemporary choreographer

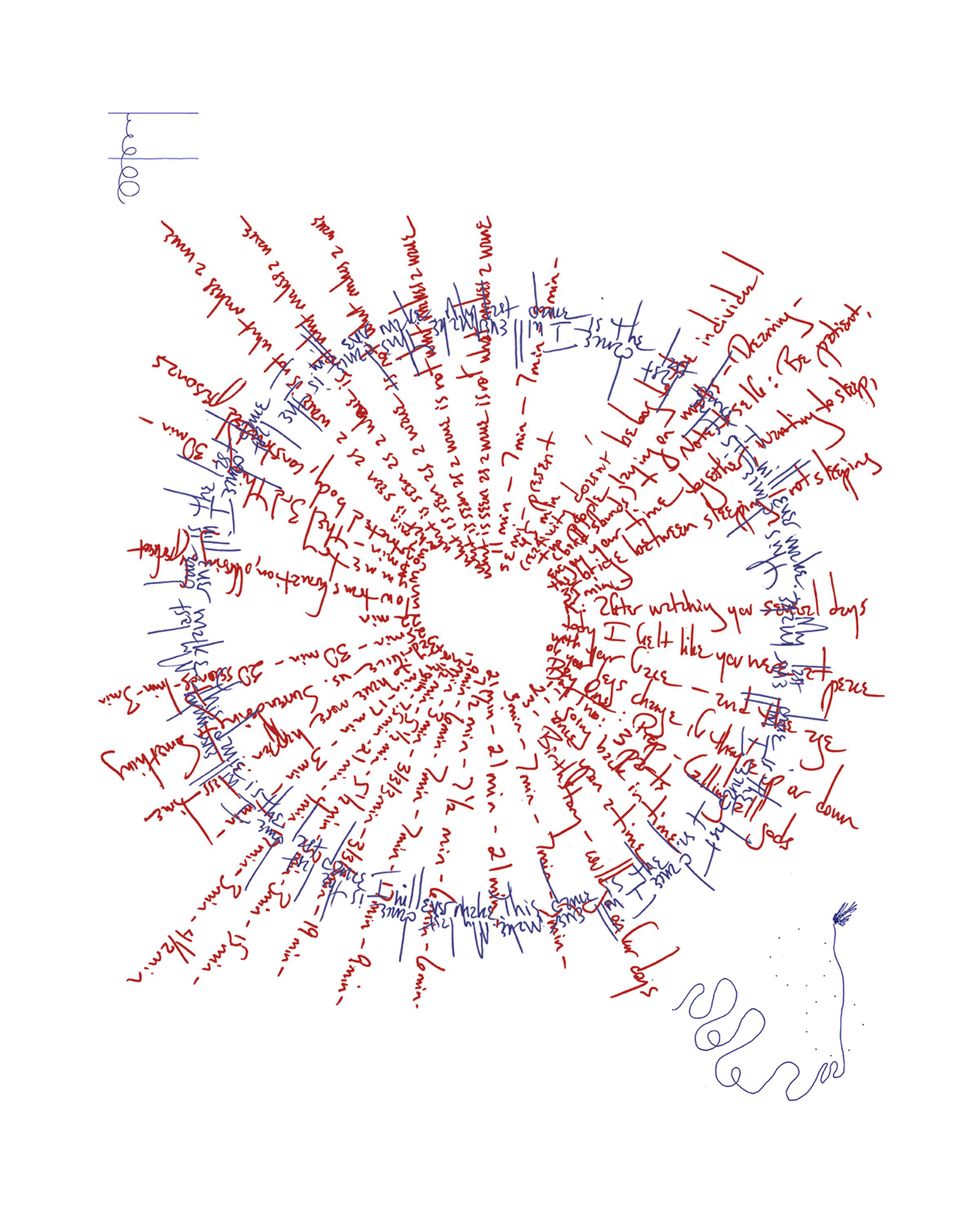

“I don’t make scores like this. I’ve never had a drawing practice. I’ve never had a writing practice. Dance has been it. Then I stopped dancing, and that felt incredibly intense. The lines in the middle, those two rings, say, ‘My last dance is the last dance I will ever make. This dance is the last dance I will ever make.’ It’s very much what I was feeling. The spokes are from a project I’d started in January 2020 in India with Kapila Venu that was supposed to be a two-year process, and then it just ended. They’re snippets, timings, directions, notes, selections of our three and a half weeks together. It holds that piece. It holds us. Maybe this is our duet. I hope it’s not going to be the only artifact of it, but right now, it is.” —Wally Cardona, contemporary choreographer

“I considered a score as a set of directions, or what to do. And so the set of directions I made are trying to tell people to get moving. The step is just something I made in my living room that felt good to do to a lot of different pieces of music. It probably would be described as a ‘line dance.’

“When I think about work that’s collaborative, it’s always in a move-y or sounds-y kind of way. There’s nothing that moves or makes sounds about a print. I also just have the most horrid visual art skills. But I was hoping someone would hang this on their wall someday—specifically a pediatrician, or someone who works with kids. So I enlisted Isabela Dos Santos as an animator and illustrator. I said, ‘Here’s what I’m thinking,’ and she kind of went to town with it, drawing lots of footsteps.” —Caleb Teicher, tap and Lindy hop choreographer

Courtesy CAP UCLA

Courtesy CAP UCLA

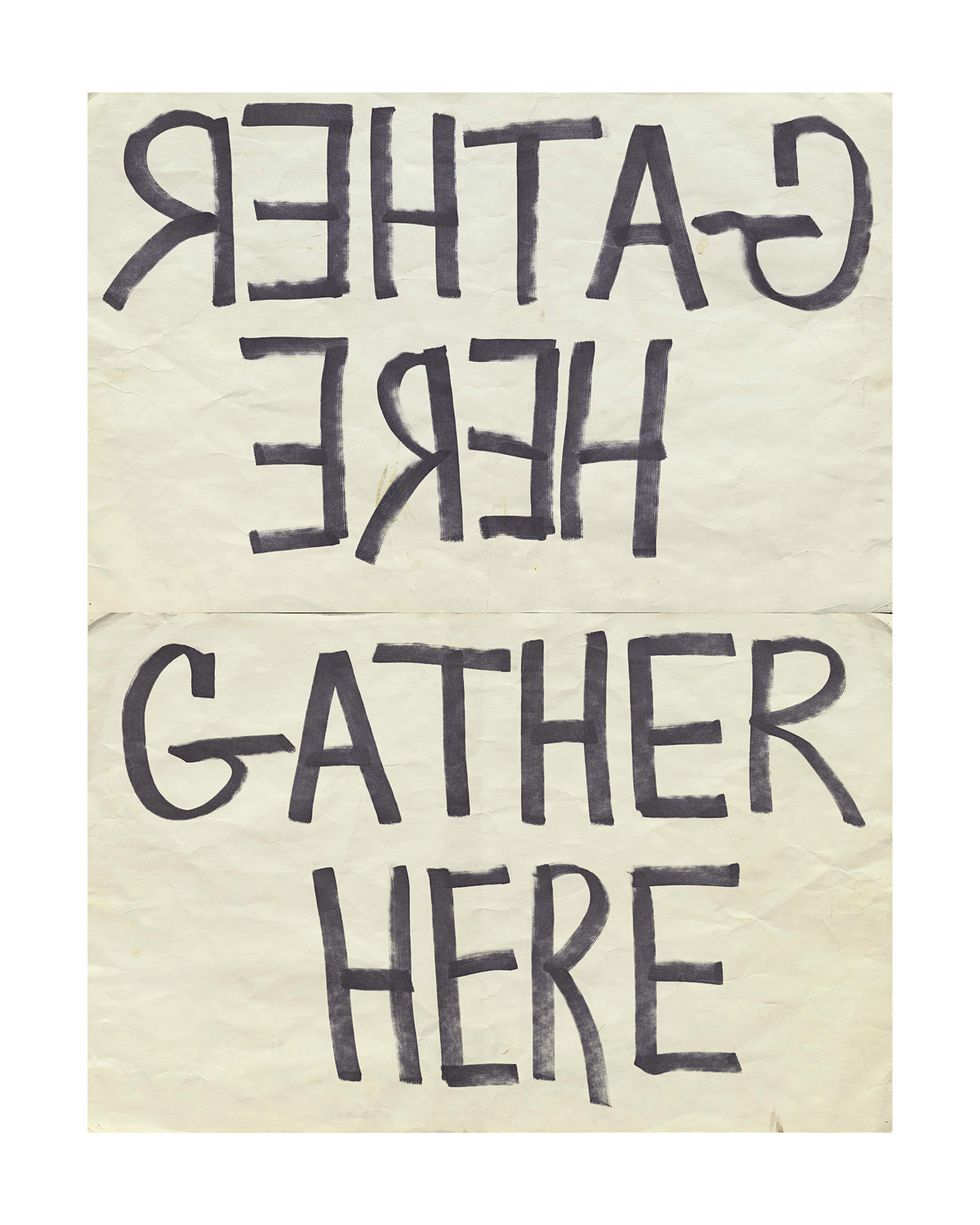

“The ‘GATHER HERE’ sign is an archive of many gatherings. I hold it over my head during performances of SHORE; The Ways We Love and the Ways We Love Better — Monumental Movement Toward Being Future Being(s); and, most recently, in the Save East River Park march.

“I love notebooks. Also written scores. Whether it’s paper or fish skin or quilts—the marks, drawings, words or, as my friend Karyn Recollet describes, glyphs—these held, archived, made-visible, made-explicit visions for the future, cartographies of other worlds, are our future technology devices, the ones we make, hold, care for, return to, share, expand.” —Emily Johnson, director of Catalyst

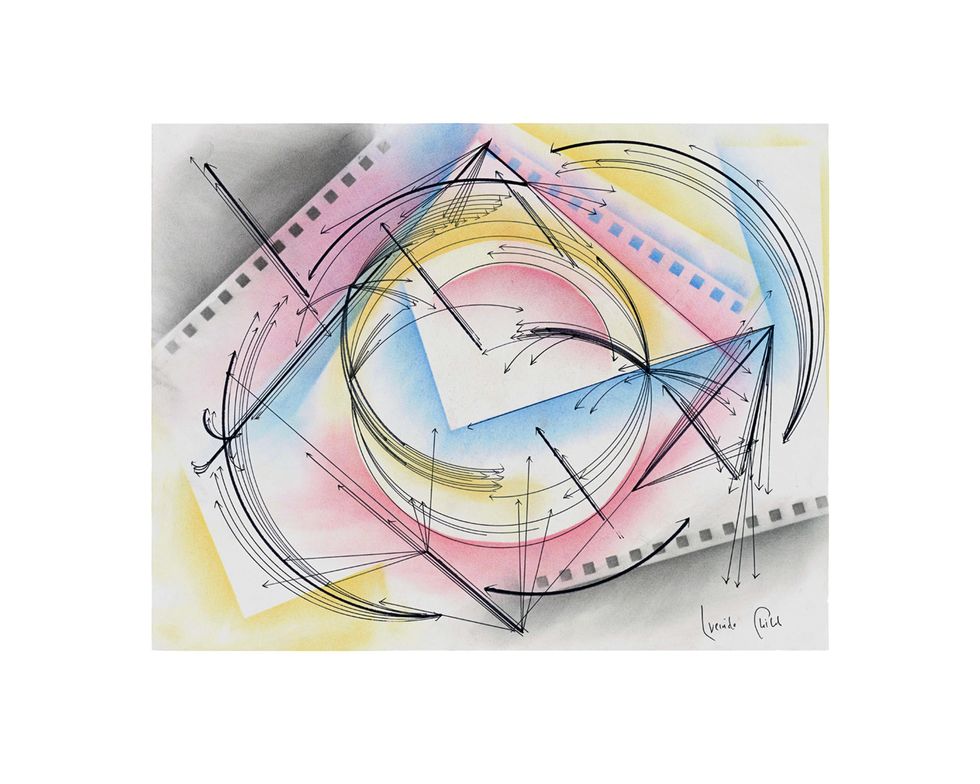

“You know when you’re looking at the dance in a two-dimensional form from an overhead point of view—which is what the score is—there’s no time element, so you’re seeing everything kind of in a flash. I’m able to see options that I wouldn’t necessarily see in rehearsal with the dancers. It’s another way of looking at the piece, and thinking about the piece.” —Lucinda Childs, postmodern choreographer

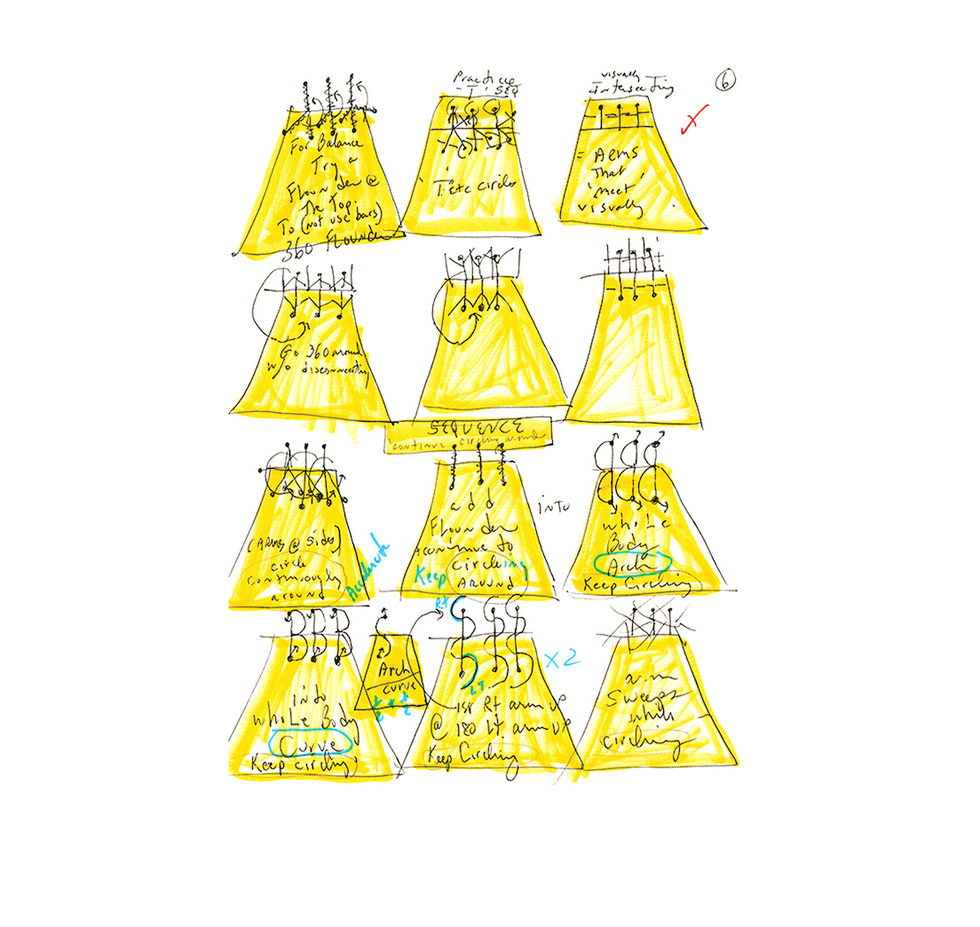

“I spend a lot of time drawing what I imagine could happen, which in most instances is all wrong because I can’t understand what the forces or the acceleration or the power that gets generated with centripetal force, etc., might be.

“Once I get a few hunks of action together, I draw them out and try to eliminate the things that I’m not going to spend rehearsal time trying. ‘Cause I have a sense that they are probably going to be not interesting, not cogent. My company members get the drawings and they can read some of them.” —Elizabeth Streb, founder of STREB Extreme Action

“I was so self-conscious about making a score. And whenever I feel that way, like, ‘Oh, my god, I’m not capable or skilled or prepared for this,’ I go back to vulnerability. And I think, ‘Okay, the deeper I dig, the more sincere the expression will feel.’

“My creative mind went to working with these two women, Leah Verier-Dunn and Loren Davidson, who are collaborators and dear friends. I ripped out those two pages from a journal for a process that’s coming up. I’m one of three sisters, and we all wore that same Communion veil. So I felt like, you know, me and my two sisters, and these two women—it felt related in some way. I saw this as texture and color and memory and personal history and cultural history, which are such a major part of how I process and create work. I thought of this veil as sort of the place where these ideas live.” —Rosie Herrera, dance theater choreographer

Interviews by Courtney Escoyne, Madeline Schrock and Jennifer Stahl.