To Post, Or Not To Post? Learn How to Curate Your Digital Dance Footprint

On a blindingly hot Saturday last September, choreographer Joanna Kotze premiered Big Beats for a small audience gathered in Manhattan’s Riverside Park. Just 15 minutes long, Big Beats, which featured a cast of 20 brightly dressed downtown dancers moving synchronously in architectural formations, was presented for free. Having used up her grant money and funding from the presenter to compensate the dancers, Kotze paid for a professional videographer out of pocket. Just as she usually does after a work’s premiere, Kotze posted the whole thing on her website and shared the link with her followers via her newsletter and social media. The approach, particularly in sharing choreography that was shorter than her typical evening-length pieces, worked: Kotze’s now working out commissions to set Big Beats at two schools, a festival and a company. “I know that one of those presenters saw it in person, but the other three saw the video,” she says.

The advent of online accessibility, particularly in the wake of a pandemic-influenced digital surge, means that choreographers like Kotze are constantly asking themselves the same question: How much work is the right amount to be posting online? It’s a complex calculus, asking artists to become experts in marketing, video editing and budgeting, in addition to dancemaking. But when it comes to curating your digital dance footprint, finding the sweet spot between too much and too little can yield a huge payoff, allowing for all kinds of new opportunities.

Share Your Gifts

For many dancemakers—particularly those who didn’t grow up with social media—the concept of constantly having to market yourself in order to stay relevant can feel exhausting. But Nel Shelby, a dance videographer who’s documented performances since 2001, has developed a more positive approach: “I learned early on that marketing’s just a way to share your unique gifts,” she says. “Putting dance online is a way to get people in all corners of the world seeing you, which could get someone really excited about your work.”

But how are dancemakers supposed to sift through the mercurial web of social media sites in order to know where to direct their time and energy? Jennifer Archibald, artistic director of Arch Dance Company and resident choreographer for Cincinnati Ballet, considers the diversity within her audiences when deciding where to post. “A 70-year-old director might not necessarily have an Instagram account,” says Archibald, who will focus on Facebook, LinkedIn or YouTube for that demographic. She also answers inquiries for commissions with a password to her private Vimeo page, where producers can view full-length versions of her repertoire. But when advertising for her summer program ArchCore40, Archibald posts short commercials on Instagram, where the intensive’s target attendees—17- to 30-year-olds—spend more of their time.

Invest in Documentation

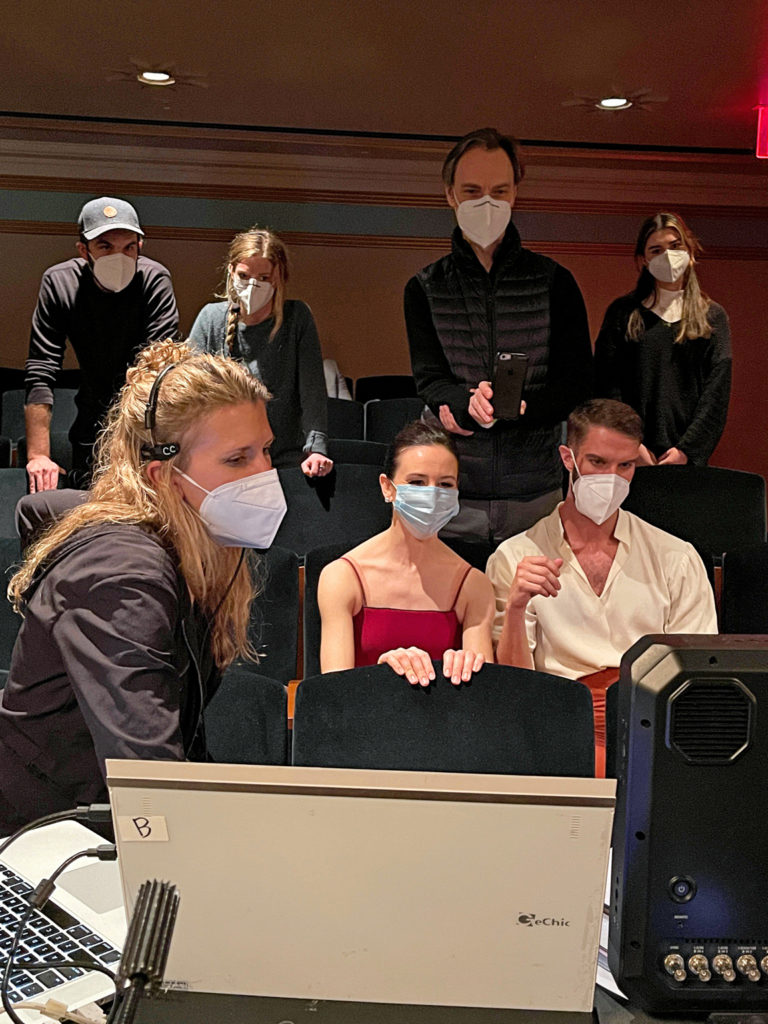

Though Kotze could have had a friend shoot Big Beats on an iPhone, she made the decision to pay a professional videographer—and says it was worth it. “It’s part of the formula,” she says. “For people to really understand the work, you have to put in the effort for documentation.” Shelby says she’s noticed that the artists who consistently invest in documenting or livestreaming often find continued success over the years. During the pandemic, she and her team also discovered the benefit of having camera-only runs, allowing the videographers to rehearse their movements alongside the dancers and then filming specifically for camera. “The best products are when I have the choreographer sitting right next to me behind the monitors and they’re giving me notes just like they would dancers onstage, and then I’m giving my team notes,” adds Shelby. “It becomes a complete collaboration.” This kind of intentionality yields much stronger results, leading to more opportunities for dancemakers down the road.

For Archibald, preparedness is key. She aims to always have digital packages of her materials ready to share. “If you’re sleeping on it, someone else is working,” she says. “If a producer on the subway asks, ‘Hey, can I get a video of your work?’ then you should be able to send it to them before they walk out onto the platform.”

Fear of Plagiarism

Anytime a choreographer puts their work online, there’s an inherent chance that it can be stolen and copied, without credit. But to commercial talent agents Julie McDonald and Tony Selznick, it’s a risk infinitely worth taking. “The internet is free game for everybody. I say to artists ‘Be careful,’ ” says Selznick. “Don’t put out the stuff that you’re worried about protecting.”

Selznick and McDonald have seen numerous artists greatly enhance their careers by posting their work online. In September 2020, during the height of the pandemic, their client James Alonzo posted A Brand New Day on YouTube, a high-energy, in-the-streets piece set to a song from The Wiz. Although he was relatively unknown at the time, the video’s success helped him score shows on Broadway and in Las Vegas. “If he was worried about getting his choreography stolen, he maybe never would have posted, but his goal was to have his work seen,” says Selznick.

The Push for Accessibility

Most everyone in the dance world can agree that seeing something online is simply not the same as seeing it in person. But offering a virtual option doesn’t have to take away from the in-theater experience; instead, it can just make it more accessible. For the premiere of Kotze’s new full-length work ‘lectric Eye at Brooklyn’s Irondale in February, she sold discounted tickets for a one-night-only livestream of the show. “I would prefer people to see it live, but I was excited about having an option for people who don’t feel comfortable going to a livee show, or who live across the country,” she says.

Since the start of the pandemic, Shelby has seen the benefits of that kind of accessibility again and again. After working with The Juilliard School to livestream its New Dances program, she heard that people all over the world tuned in who’d never been able to see the famed conservatory in action before. Shelby also livestreamed Barnard College’s fall concert, allowing some students’ parents and remote family members the chance to see their loved ones perform for the first time; Barnard plans to continue the practice even after theaters return to their full capacities.

Archibald dreams of taking accessibility one step further: Last fall, Tulsa Ballet debuted her Breakin’Bricks, a full-length piece painstakingly created to commemorate the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial. For the process, Archibald brought in seven Black dancers to work with the predominantly white company. She sees the piece as historic. “But the only people who saw it were in Tulsa, and it’s something that could have a huge impact on ballet,” says Archibald. University dance departments eager to add it to their curriculums have asked Archibald for a link, leading her to reimagine how dancemakers could share their work. “We should be selling digital versions of our pieces like how people walk into the bookstore at the beginning of the school year and purchase books,” she says. “For some reason, the dance industry has never thought that our works can be monetized on that level. But we are actually worth a lot; that’s what we need to be aware of when we’re putting ourselves out there.”

Social Media Savvy

Feeling overwhelmed by the plethora of platforms out there? Focus on what makes most sense for your footage and who you want to reach. Though some choreographers make use of Facebook, YouTube, TikTok and LinkedIn to share their work, Instagram and Vimeo are by far the most popular.

Instagram

Commercial talent agents Julie McDonald and Tony Selznick create a customized approach for each client, but Instagram remains their go-to. “It’s the primary platform we promote,” says Selznick. They’ve found the visually based platform has led to success with their artists. Choreographers Jennifer Archibald and Joanna Kotze both use the app to share photos and short clips of their work. And although Instagram accounts often veer into the personal, Archibald and Kotze insist on only showcasing their professional lives. “The world has made a shift in marketing, but for me, social media is strictly work,” says Archibald. “You don’t know what I’m going to eat in the morning.”

Vimeo

If Instagram is best for teasers and reels, Vimeo is great for posting complete pieces, and can become an easy-to-use digital archive for choreographers to organize their oeuvres. “After a premiere, I put a link in my bio on Instagram to the piece on Vimeo if people want to see it,” says Kotze. Archibald often posts full works privately on Vimeo; she’ll share a password with directors and producers interested in commissions. “You can include more of a lengthy description on what exactly the piece is about and give credit to everyone who was involved,” she adds.