It’s Time to Acknowledge the Muses

Watching FX’s “Fosse/Verdon,” one thing comes across very clearly: Gwen Verdon was far more than just an extraordinary dancer—she was a creative force.

The series, adapted from Sam Wasson’s 2013 biography “Fosse,” originally planned to focus solely on the choreographer. But the creators retooled it to highlight Verdon and Fosse’s creative partnership after they researched the pair and learned just how much Verdon’s vision shaped Fosse’s (and, well, after the #MeToo movement made his behavior seem especially unsavory). As producers Lin-Manuel Miranda, Andy Blankenbuehler and Thomas Kail said in a joint statement prior to the premiere:

“Bob Fosse ignited a revolution in American dance, theater and film. But, in contrast to the well-worn myth of the visionary artist working in solitude, Fosse’s work would not have been possible without Gwen Verdon, the woman who helped to mold his style—and make him a star.”

Much of Verdon’s contributions came from her work as an uncredited assistant and dance coach. But they also happened in the studio where, working one-on-one with Fosse, she offered her creative ideas and instinctual sense of style.

“Fosse/Verdon” highlights this right from the opening scene of Episode 1: Fosse is setting a phrase on Verdon for “Big Spender” and asks her to bend a leg. She sinks into her standing hip and turns out the working leg in a subtle plié; he asks her to turn it in, takes a look, then says, “Yours was better.”

It’s not hard to guess which version he went with.

Anyone who’s been in a dance studio during the creation of a new work knows the process is typically a two-way street, with the choreographer playing off of whatever the dancers in front of them have to offer. Dancers are not passive receptacles for genius choreographers—they’re collaborators.

Yet how often do the dancers get recognition for their contributions?

It’s often only insiders who understand the extent of a dancer’s influence. Once, when speaking to Brian Brooks about what it was like to work with Wendy Whelan, he told me:

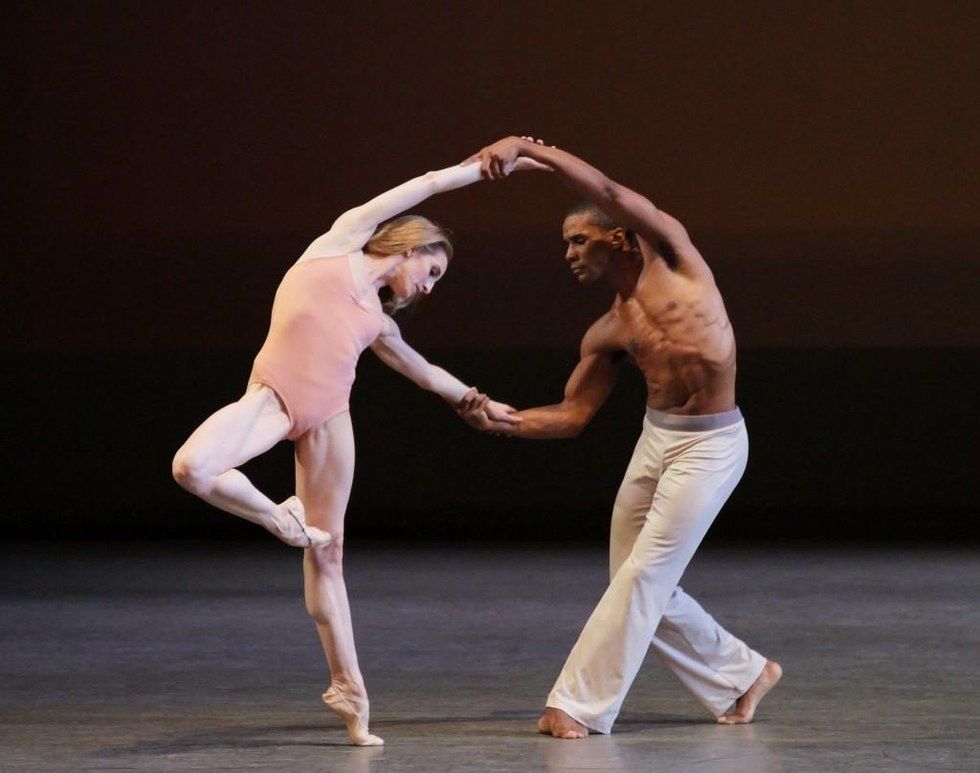

“Although she’d never call herself a choreographer, her intuitive suggestions and her instincts contribute on an exceptional level,” says Brooks…. He had an epiphany recently while watching Wheeldon’s

After the Rain…he could see Whelan in the choreography, particularly her physical sense of timing. “Her urge to suspend, pause, elongate—I saw that integrated, and I feel it when collaborating with her.”

After the Rain Paul Kolnik, courtesy NYCB

Sometimes, dancers’ contributions are far more than phrasing suggestions, or a tweak or adjustment here or there. Particularly in modern or more experimental dance contexts, whole movement phrases are often entirely created by the dancers themselves, while the choreographer curates, molds and directs.

In the downtown dance world, choreographers who particularly lean on their dancers for movement ideas commonly credit their work as choreographed “with the dancers.” Kyle Abraham recently brought this practice to New York City Ballet—2018’s The Runaway is officially cited as being choreographed by “Kyle Abraham in collaboration with NYCB.”

It’s just a simple few words, but there’s something powerful in specifying that dancers are collaborators. It affects how we see the work—the dancers become part of the piece, not just performers of it.

Recognizing dancers this way could change how we think and talk about new work. It could put an end to the stereotype of the lone genius, which underplays the role dancers have in a piece’s (and choreographer’s) success. It could make dancers feel far less taken advantage of. It could give fans a whole different kind of appreciation for their favorite pieces.

I’ll admit that even I, as someone who thoroughly understands how the creative process works, never once thought about Verdon’s influence on the moves I love to imitate in my kitchen. Until now. And it only makes me love them even more.