Remembering Judith Jamison (1943–2024): Dancer, Choreographer, Artistic Director, and Keeper of the Flame

During her extraordinary lifetime, Judith Jamison built a legacy not only as a performer and leader of singular vision, but also as a champion of numerous other dance artists. In the tributes to Jamison that have proliferated since she passed away on November 9, many have marveled at the scope of the longtime Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater director’s influence. “Thank you for teaching me and generations of artists how to FLY,” wrote Alicia Graf Mack, a former AAADT dancer, current dean and director of Juilliard Dance, and incoming artistic director of AAADT.

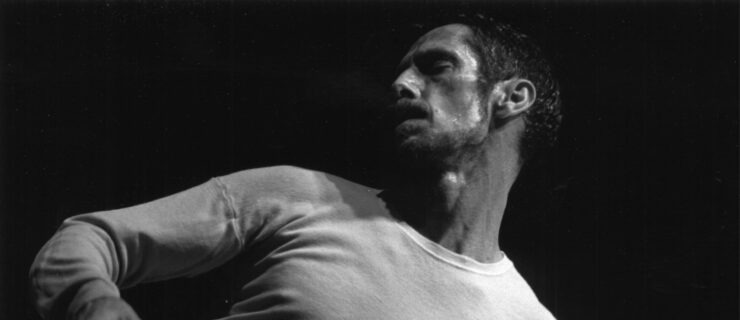

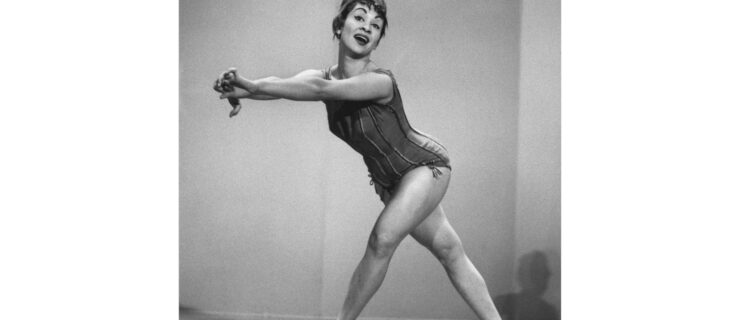

Of course, the most prominent champion in Jamison’s own career was the legendary Alvin Ailey, who spotted her in 1965 during another choreographer’s audition. He invited Jamison—whom he described in 1973’s Current Biography Yearbook as “extraordinary,” “beautiful,” and “gangly” (she was nearly 6 feet tall)—to join his company. In AAADT, Jamison captivated audiences around the globe. Her indelible performance in Ailey’s tour-de-force solo Cry, created on her in 1971 and dedicated to “all Black women everywhere, especially our mothers,” astounded audiences and critics alike. Beneath a 1976 New York Times Magazine cover photo of Jamison, the copy reads “Don’t call me a star. Call me a dancer.” Yet, as critic Deborah Jowitt’s article insisted, the then–33-year-old Jamison was a star, “one of the few so-called ‘modern’ dancers to achieve fame.”

Jamison’s story began in her hometown of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where at 6 years old she started taking ballet with the legendary Black teacher Marion Cuyjet. Training in acrobatics, tap, jazz, and what was then called “primitive” dance followed. A master class with Agnes de Mille at the Philadelphia Dance Academy prompted an invitation to guest with American Ballet Theatre in the choreographer’s 1965 work The Four Marys—years before ABT would accept Black ballerinas in its ranks. Not long afterwards, the Ailey discovery paved the way for Jamison’s phenomenal rise.

As a leading dancer with AAADT, Jamison’s technical and emotional prowess blossomed in a multiracial ensemble where dance was both formal and theatrical, with an eclectic repertoire that centered the Black experience. Jamison shone in Ailey’s Revelations, Blues Suite, and Masekela Language; Talley Beatty’s Congo Tango Palace; Geoffrey Holder’s The Prodigal Prince; Pearl Primus’ Fanga; and works by Anna Sokolow, Joyce Trisler, and Louis Falco. In Pas de Duke, a spirited homage to Duke Ellington, Ailey memorably showcased the virtuosity and musicality of Jamison and partner Mikhail Baryshnikov in a playful competition.

AAADT served as an American cultural ambassador, traveling around the world. Its rigorous domestic and international touring schedule enhanced the company’s profile, and Jamison’s. As her popularity grew, Jamison ventured beyond Ailey. There was a stint on Broadway in the musical Sophisticated Ladies, with the legendary Gregory Hines; there were guest gigs with San Francisco Ballet and Maurice Béjart’s Ballet of the Twentieth Century, among others. In 1988 she formed her own company, The Jamison Project. Her first choreographic work, Divining, expressed a sophisticated, compellingly distinct aesthetic.

That perspective would come to shape AAADT when, at Ailey’s request, she took over as artistic director after his death in 1989. Performing a delicate balancing act, Jamison maintained the Ailey spirit while injecting what critic Anna Kisselgoff called “dance in a post-modern mode.” As Ailey had introduced a new generation of modern choreographers, so Jamison introduced Lar Lubovitch, Donald Byrd, Rennie Harris, and Jawole Willa Jo Zollar.

She nurtured the company organizationally, as well, helping to get it on solid financial footing and to secure its permanent home in midtown Manhattan. Joan Weill, chairman emerita of the Ailey board of trustees, witnessed Jamison’s gifts as a leader firsthand. “I came to know this great artist as a passionate, creative, caring person, as well as a great friend,” Weill says. “Working with Judi to build the organization was a labor of love. I will miss my dear friend terribly, but her spirit, determination, and selfless caring will be with me forever.”

Now, evidence of Jamison’s successful stewardship is visible in both the Ailey building that towers over the corner of 55th Street and Ninth Avenue, and in the hundreds of diverse dancing bodies that swing through the building’s revolving doors daily. After all, as Jamison always reminded folks, Ailey said, “I believe that dance came from the people and that it should always be delivered back to the people.” That was his mission—and her life’s work.