Without $1 Million By December, This Essential Residency Program Might Be In Danger

Just last year, the previously Rockville, Maryland-based American Dance Institute—now called the Lumberyard Center for Film and Performing Arts—moved to a 30,000-square foot-former lumberyard in Catskill, New York, spending 5 million dollars to renovate the building.

Now, the organization needs to raise 1 million dollars by the end of 2019, or risk having to shut down their pre-premiere technical rehearsal program.

What happened between last May, when the much-talked-about facility opened its doors, and today, when Lumberyard’s signature program faces potential closure?

The Lumberyard campus in Catskill, NY

The Lumberyard campus in Catskill, NY

Alon Koppel, Courtesy Lumberyard

The costs of opening the facility were just part of the problem, says Lumberyard’s executive and artistic director Adrienne Willis. It cost more to get the building operating than they expected, and some support they were counting on didn’t come through.

But Willis says the problem Lumberyard is facing is a more systemic one, that speaks to how the creation process has changed in recent years—but funding models haven’t kept up.

Since 2011, Lumberyard has been providing artists with space to hold extended technical rehearsals before a work’s premiere. (Part of the reason for their move was proximity to New York City, where most of these works end up premiering.) Lumberyard is the only facility of its kind in the United States, giving artists one or two weeks in the space with housing, a full crew and a public work-in-progress showing.

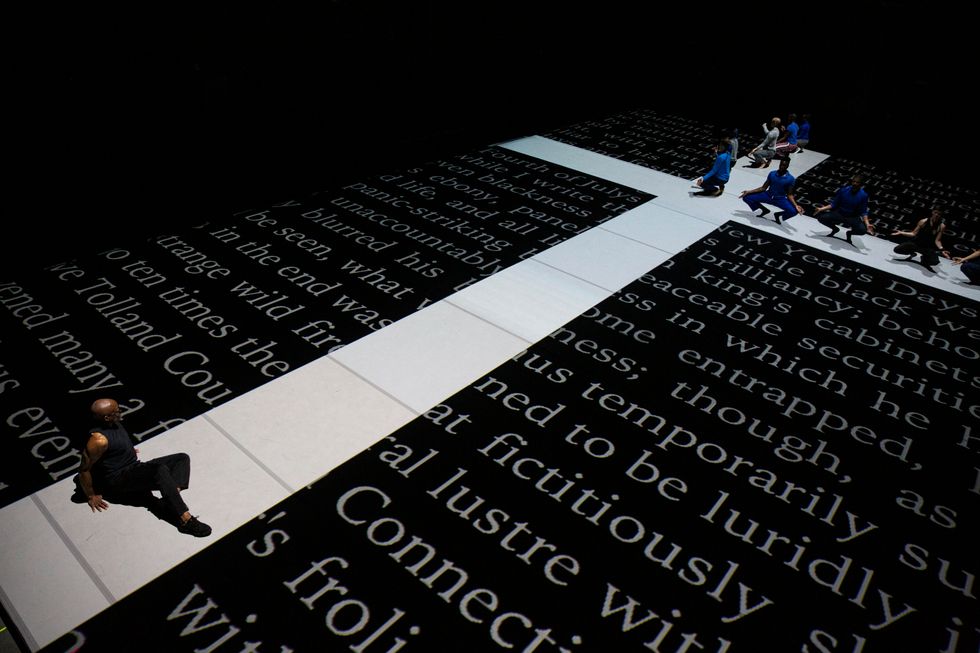

Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company perform a work-in-progress showing of On The Water at Lumberyard.

Baranova, Courtesy Lumberyard

Lumberyard is meeting an urgent need, considering most presenting venues—especially those in New York—aren’t able to give artists extended time for technical rehearsals. And yet, Willis points out, artists today are using technology in their work more than ever, in more advanced, nuanced and integrated ways.

“The creation model has changed dramatically over the last decade,” says Willis. “Artists used to come to us a week before they premiered a work at Brooklyn Academy of Music. Now they come at the early stages of their work. We’re at a critical point where we don’t have the support structures and as a result we risk sacrificing American artistic innovation.”

According to Willis, philanthropy doesn’t see this as an urgent problem, or one they’re willing to devote dollars to. “It’s been very difficult for us to raise awareness of this issue,” she says. “The people feeling this the most are the artists who are making this type of work that doesn’t have a traditional creation model. They don’t have a collective voice.”

As a result, Lumberyard has struggled to gain philanthropic support for their technical rehearsal program aside from their initial seed money. “It’s difficult when your mission is so nuanced,” Willis says. She says they’ve struggled with foundations who say that if the work is being presented at BAM and they already fund BAM, why should they fund Lumberyard, too?

This past year, Lumberyard housed six productions in development, because that’s what they could fund. But Willis points out that they could have done up to 40 based on the time and space they had available—and the more artists they can work with, the smaller the cost-per-production will be. “The amount of impact we could have could be bigger at a fraction of the cost,” she says. “We’ve already created a location, a program, and a facility that is much higher-impact than in the city.”

Yes, Lumberyard could make their facilities available to those artists who are able to pay. “But we don’t want to be in a situation where our space is only open to those who can afford it,” Willis says. “We want to make sure the space is for those with household names and those who are emerging.” (They’ve hosted everyone from Kyle Abraham to Vicky Shick to Raja Feather Kelly to STREB.)

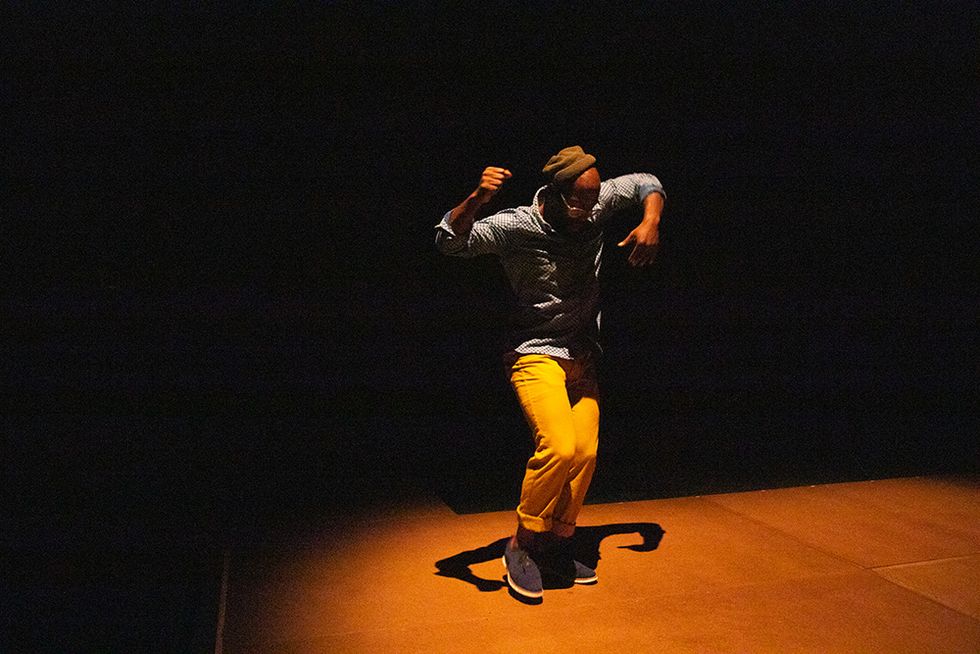

Ephrat Asherie Dance performs a work-in-progress showing of Underscored at LUMBERYARD.

Elizabeth Ibarra, Courtesy Lumberyard

As of today, Lumberyard has raised around 20 percent of the one million dollars they need to keep the program afloat. (They launched the fundraising effort in July, and are not on track to meet their goal, Willis says.) It’s not a one-time need, either, she says: They’ll have to raise one million dollars for the program annually for it to continue operating in its current iteration.

But Lumberyard is open to new models—which is why they’re looking not just for funders, but for partners—including perhaps presenting organizations who could co-fundraise or build Lumberyard’s technical rehearsal program into the cost of production. “We’re not tied to curation, or any sort of funding model, or the process,” says Willis. “We’re open. Our mission was to build this for the field. We needed to take a pause and make sure we’re getting the whole field on board.”

They’ve also recently released a white paper about access to technical rehearsals, and will be co-hosting an event with Bill T. Jones at the Park Avenue Armory on November 19 to bring stakeholders together.

Without the technical rehearsal program, Lumberyard would continue operating as a rental facility for film and television, as well as a community space with programs for local children and teens.

But the loss of the technical rehearsal program would certainly be felt in the New York dance community. “There hasn’t been a single artist who didn’t say that if they didn’t have this time at Lumberyard, this piece wouldn’t have happened,” says Willis.