The New York Public Library’s “Border Crossings” Exhibit is Part of a Developing Conversation About Modern Dance’s Radical Roots

In 1915, 7-year-old José Limón and his family fled Mexico in the midst of the Mexican Revolution, eventually settling in Los Angeles. Limón’s early years were shaped by trauma: In wartime Mexico he saw his uncle shot and killed, and in his new home he was bullied for his poor English. “Not having the tools to assimilate in a healthy way really shaped his vision as an artist,” says Dante Puleio, the current artistic director of Limón Dance Company. “He grew up in America, but he still felt like an outsider. He was constantly facing this sense of exile.”

To contemporary audiences, Limón’s sense of identity might seem intrinsically linked to his artistry. But when Puleio took over the Limón Company in 2020, he realized that the group hadn’t worked with a single Mexican choreographer (though it had engaged other Latinx dancemakers) besides its founder, who passed away in 1972. While a few early Limón pieces exploring his culture remain in rotation, his 1939 Danzas Mexicanas, for instance, had been lost almost entirely after the choreographer did not teach it to any other dancers.

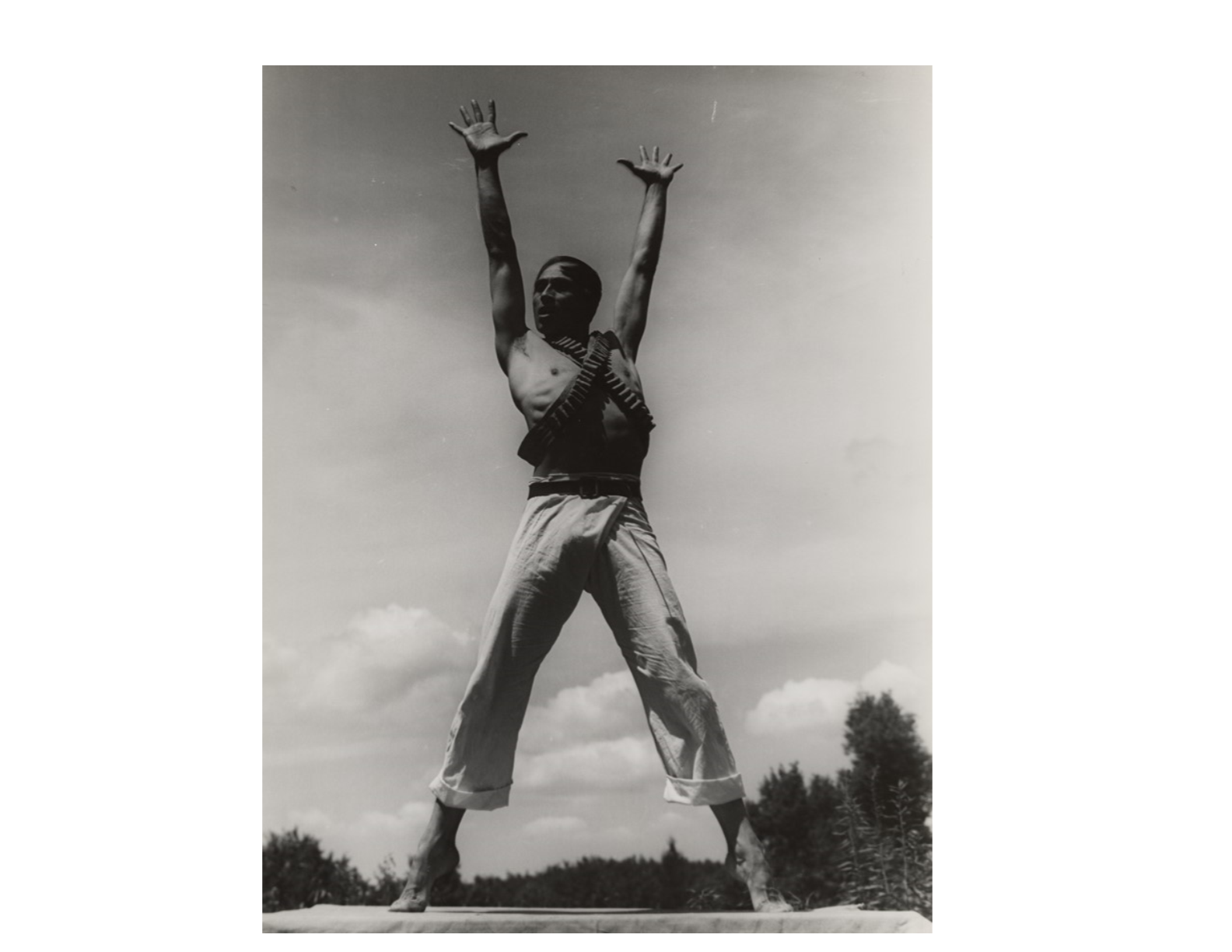

For decades, the development of American modern dance was largely seen as a reaction to classicism. But many other forces drove modern pioneers’ art. “At the heart of modernism, there is trauma,” says art historian Bruce Robertson. Robertson and dance historian Ninotchka Bennahum are the curators behind the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts’ exhibit “Border Crossings: Exile and American Modern Dance, 1900–1955,” which recognizes the foundational—and often overlooked—contributions that marginalized dancers, including Limón, made to the development of American modern dance. The exhibit, which runs in New York City through March 16, 2024, and at University of California, Santa Barbara, from January 25 through May 15, 2024, considers the genre’s more radical roots. “Why don’t we see the traumatized body, the stateless body, the asylum-seeking body, as a way of analyzing and seeing dance?” asks Bennahum. “Form and content, codified technique. Why is that the only thing that produces an artist of greatness?”

It’s a question that extends beyond the exhibit’s 1905-to-1955 time period. While “Border Crossings” considers who’s been left out of the historical narrative, some artists currently working with modern traditions are also trying to reframe the legacy of modern dance, acknowledging how issues of identity and politics have shaped, and continue to shape, the form.

Following in the Founders’ Footsteps

For the leaders of legacy modern dance companies, new commissions can be a way to honor under-recognized aspects of their founders’ legacies. One of Puleio’s first commissions after becoming director of the Limón Company went to Mexican choreographer Raúl Tamez. The resulting work, Migrant Mother, partially inspired by Limón’s 1951 trip to Mexico City, won a 2022 Bessie Award. “I felt like I had to go back to the roots and rediscover who José was, why he made the work he made, and then work with choreographers that are living and breathing in that same ethos,” says Puleio.

The Martha Graham Dance Company is revisiting its founder’s radicalism, honoring the countercultural elements of Graham’s oeuvre through a combination of reconstructions and new commissions. MGDC artistic director Janet Eilber says that though Graham always claimed she was apolitical, her work tells a different story: In 1936, Graham famously turned down an invitation to perform at the Berlin Olympics because she did not support the persecution other artists were facing in Germany, coupled with the fact that her company was largely made up of Jewish women. In reaction, she created Chronicle. In 1937, she made Deep Song and Immediate Tragedy to honor the women in the Spanish Civil War. And her 1944 Appalachian Spring featured the then-new company member Yuriko and sets by Isamu Noguchi, both freshly released from Japanese incarceration camps.

“It was a statement,” says Eilber. “Among the many other messages in Appalachian Spring, there’s the element of America being made up of immigrants, and needing to assess its own morals and how we treat people in this country.” This month, the Graham company will restage some of those early solos at the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a complement to an exhibit about American politics in the 1930s.

Choreographers making new works at legacy modern companies are discovering ways to bring their 21st-century voices into dialogue with older traditions. When the Paul Taylor Dance Company commissioned choreographer and Ballet Hispánico School of Dance director Michelle Manzanales in 2019, she found herself at a crossroads. Manzanales, who is Mexican American, often references her heritage in her choreography, but the Taylor company’s repertoire largely does not reflect that approach. “I love to use music in different languages, but I wondered how the Taylor audience would react to that,” says Manzanales.

Ultimately, she chose not to compartmentalize that part of her identity. Her piece, Hope is the Thing with Feathers, which premiered in 2022, is set to a playlist of songs in both English and Spanish, with the Taylor dancers even lip-syncing lines from the Mexican musician Carla Morrison’s “Pajarito del amor.” “It’s interesting how, as a society, we want to see this part of Limón or that part of Limón, or this part of Michelle or that part of Michelle,” Manzanales says, “but really we can’t escape who we are.”

Carrying the Message Forward

Modern dance’s recontextualization efforts are reaching beyond the stage and expanding into educational and outreach programming. Chicago-based artist and educator Vershawn Sanders-Ward, for example, is working to bring more aspects of the modern dance matriarch Katherine Dunham’s legacy into the studio. Dunham was also an anthropologist who traveled throughout the Caribbean, bringing dances from the African diaspora back to the U.S. Her art and activism are so deeply interwoven that the one can’t be siloed from the other—which is one of the reasons she has been pushed to the sidelines of modern dance history.

“Miss Dunham was clearly a multi-hyphenate. She was a performer, a choreographer, a scholar, and an educator,” says Sanders-Ward, who is in the process of becoming a certified Dunham instructor. Sanders-Ward makes it a point to incorporate the cultural background of Dunham technique when teaching, and hopes that Dunham’s activist legacy becomes a more prominent part of dance education.

Elsewhere, the New York Public Library has created an educational curriculum around “Border Crossings,” and Bennahum will be hosting a Limón symposium at University of California, Santa Barbara, in January 2024 to bring scholars and artists together in conversation. Next year, Graham, Limón, and other companies will join forces for a conversation at 92NY “to look at the iconic works of the 20th century and how they should be viewed in light of today’s conversations,” says Eilber.

Bennahum and Robertson hope that their exhibit will help dancers—and audiences—expand how they think about the modern dance canon: A more complete understanding of the diverse factors that shaped the form’s development will help better shape its future. And they stress that even their very intentional project was only able to feature a small percentage of modern dance’s overlooked artists.

“Dance history has a very long way to go,” says Bennahum. “We’re trying to rewrite the field.”