Beyond Male/Female: Nonbinary Dancers Forging Their Own Paths

“Nonbinary” is a vast container of a term. Defined by what it is not, it holds anyone whose gender identity is not validated by the binary of either male or female, whether aligned by birth (cisgender) or by transition (transgender). In between these two poles is a sprawling array of labels for individuals whose sense of gender is inherently opposed to labeling. As dancer Maxfield Haynes puts it, “People think being nonbinary is like this third gender, but it’s anything but. My nonbinary identity is an outright rejection of the concept of gender as a whole.”

This becomes tricky in a professional dance context, where anything from costumes to casting is frequently organized in male/female terms. When I was in college for dance in the 2010s, audition calls were very clear about how many men and women were desired. Today, there is a marked shift in audition-announcement language: You now see traditional calls for male or female dancers (some of which make conscious space for transgender dancers with “-identifying” in their language), open calls that specify no identity stipulations (but might have them anyway), and more pointed calls specifically looking to uplift nonbinary performers (which may or may not be ultimately tokenizing in nature).

I myself only came into a gender-nonconforming identity this past summer, and not much has changed. I make my own work, and regularly perform with a few groups, generally collaborative in process, that allow me to exist onstage in a way that feels true to me. When I have to perform an idea of a boy, I put on that costume, though my experience at male open calls has told me that, by showbiz standards, it’s not the most convincing.

But just like all the permutations of gender identity and expression that exist between two diametric poles, there are just as many experiences of dancing with them.

For some, validation comes from rejecting formative structures. Aeon Andreas, a resident artist at House of Yes in Brooklyn, New York, created their drag persona, God Complex, after a long road of formal training in ballet and modern that shifted to postmodern dance and acting in college. “No one would cast me,” they say. “I actually received a lot of negative feedback from teachers and peers.” Andreas took to choreographing, devising and directing to forge their own path, finding mentorship, collaboration and friendship through Dan Safer, with whose company, Witness Relocation, they still perform.

As a dance artist, Andreas is inspired by rock ’n’ rollers. “The physicalities of rock stars are so queer, often very androgynous, demanding and generous,” they say. “I try to encapsulate that with God Complex—a harnessing of power.” Reflecting on finally debuting their persona, they recall, “It was extremely affirming. People were saying ‘yes’ to me after years of hearing ‘no’ constantly. My understanding of myself, my gender, my personality—everything opened up with drag.”

Growing up in tap and ballet, Holly Sass was trained to be delicate and light. In the freelance concert dance world, they often felt confined within the vision of others. Masculinity was only available as a costume. A game changer was encountering contemporary partnering, first at a summer program and subsequently more in-depth in college: “It didn’t matter the size, strength or gender of a person. If you knew how to share weight and communicate, verbally and somatically, anyone could play any partnering role. That blew my mind,” they say.

Disclosure: I frequently collaborate and perform with Sass under the moniker BREAKTIME. Our duo is a playground for subverting formal training. “Any formerly rejected ideas in our other creative processes have a home with us,” they say. Outside of performance and work in film, Sass, who is also a bodyworker, founded bodies for bodies, a sliding-scale somatic-healing community of and for queer and trans individuals.

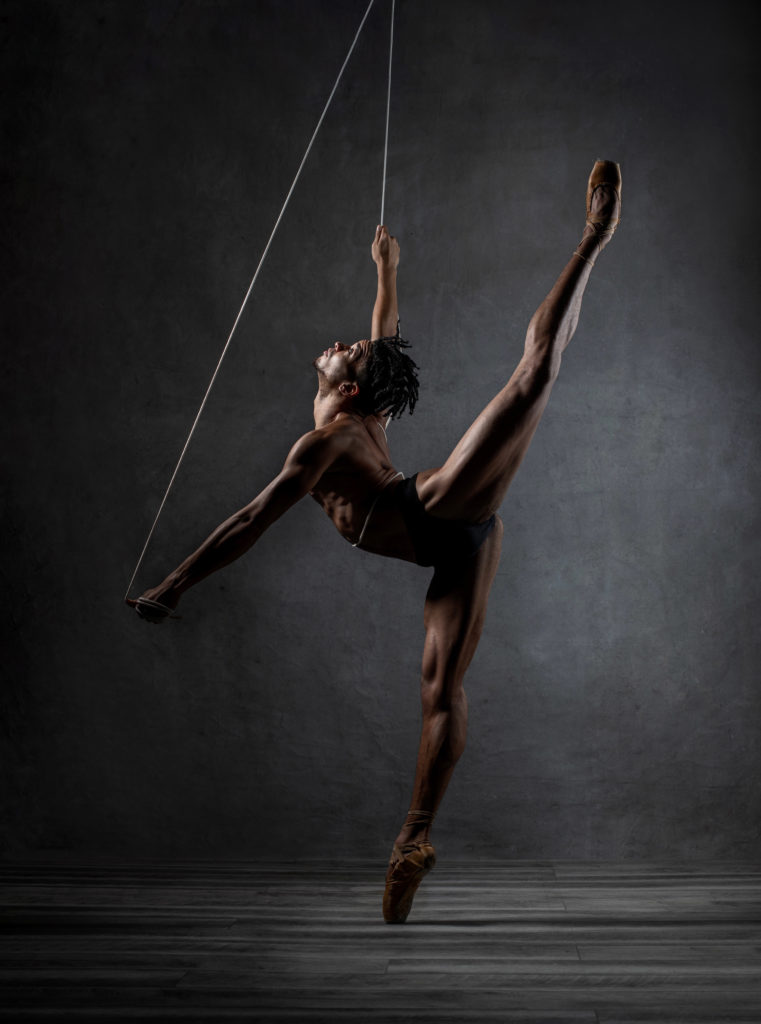

Maxfield Haynes grew up determined to pursue their interests within classical ballet’s strictures, but “I didn’t like big jumps and turns; I wanted to dance on pointe.” Haynes recalls a teacher at San Francisco Ballet School explaining a section from a variation for Albrecht from Giselle: “He claimed, ‘You have to carry yourself with pure masculine regality.’ In that moment something snapped in me,” they say. “No part of me saw myself in that role, or portraying that characterization.”

While Haynes was attending NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, former American Ballet Theatre soloist Jolinda Menendez invited them to take her pointe class after seeing them work diligently and independently on developing their technique. This self-guidance and continued dedication have led to Haynes dancing a breadth of roles they aren’t so much stepping into as actively co-creating, from having been a member of Complexions Contemporary Ballet to working currently with more explicitly queer troupes, such as Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo and Katy Pyle’s Ballez. No matter the project, Haynes’ goal remains consistent: “I’m trying to actively queer ballet every chance I get,” Haynes says. “The entire lexicon of ballet steps has no defined gender. They’re just a means to an end.”

“My nonbinary identity is an outright rejection of the concept of gender as a whole.”

Maxfield Haynes

Caleb Teicher operates under a similar mindset within another traditionally gendered form. “Lindy Hop is quite literally a binary dance—there’s the lead role and a follow role,” they explain. “Historically, leads have been male and follows have been female, but the lead/follow binary does little to illustrate the diversity of power balance and role performance in Lindy Hop.” Teicher has observed that most Lindy Hop classes today allow anyone to lead or follow regardless of gender, and many teach both roles to each participant. They credit a role-swapping swing dance group, The Double Troubles, with bringing them more fully into their preferred dancing role—as a follow.

Growing up, Teicher recalls not feeling comfortable with the “boy” or “girl” options for recital costumes in jazz classes, finding more expressive freedom in the aural focus of tap dance. Today, by focusing on the vernacular of tap, jazz and Lindy Hop, they constructively infiltrate those traditions, furthering them instead of dismantling them. One example is Meet Ella, a duet Teicher made with Nathan Bugh. “It’s in the continuum of jazz dance duets, but it doesn’t fit in the existing idioms very clearly,” they say. “It’s not a ‘brother’ act, or a class act, and we’re not Fred and Ginger. Nathan and I are there, dancing together, in conversation with the music, our bodies and each other.”

For Hans, growing up with dance as culture rather than training set them up to choose affirming movement. Hans was raised amid Caribbean communities in Miami, where salsa, merengue and bachata were standard fare at family functions and dancing was integral at parties and clubs. It wasn’t until grad school that they took on formal dance training, curating a contemporary blend of flamenco and street styles. Flamenco satisfied a search for a way to nurture their lived duality of softness and strength.

“I use my multiple modalities to formulate a circular dialogue between all my ways of creating,” says Hans, who also has a visual art practice encompassing printmaking, digital media and tattooing. They maintain a direct parallel between their queerness and their work, from how they identify as an artist to the venues in which they feel at home performing. “It makes sense that alt spaces are generative for queer folk,” they say, citing Brooklyn’s Starr Bar as an example. “These clandestine spaces have been our refuges for so long, and tend to always be the places where we can explore freely.”

As there is no one way to be nonbinary, there can be no expectation of what sort of work might come from an artist who identifies as such. What is common to these experiences, however, is that these multifaceted performers and makers are as wary of arbitrary boundaries in how they engage with their practices as they are in their personal navigations of gender.