Pam Tanowitz: "I Would Rather Fail at Something Interesting Than Do Something Boring"

When theaters shut down in New York City early last year, Pam Tanowitz didn’t know what to do with herself. She had just returned to Manhattan from Los Angeles, where her company, Pam Tanowitz Dance, had performed Four Quartets, her epic work set to T.S. Eliot’s poem of the same name. Coming up on her calendar were a premiere for New York City Ballet’s spring season, a run of her New Work for Goldberg Variations in London, her company’s Lincoln Center debut and about a dozen other engagements. Soon they would all be canceled or postponed.

While some choreographers turned instantly to the screen as a performance space, Tanowitz held back, unsure of how to keep going, or whether to keep going at all.

“At first I was very resistant,” she says. “I didn’t want to do anything, because I didn’t know how to do anything on the internet.” And like many people at the time, she was just feeling low. She looks back on last March as a period of fear, depression and boredom, with days spent watching TV and getting tarot readings from her daughter, Gemma.

Not one to back down from a challenge, she eventually began, in late April, to rehearse with her dancers on Zoom, the first step in a new creative chapter of exploring dance for the camera (and dance for the internet). But for a few weeks—and for the first time in a long time—she took a break from making new work.

Pam Tanowitz Dance in New Work for Goldberg Variations

Erin Baiano, Courtesy Tanowitz

For just about anyone with a career in live performance, the pandemic brought work as usual to a halt. But for Tanowitz, who is now 51, the halt was perhaps especially jarring, given the momentum she had gathered in the year before. After decades on what she calls “a slow path,” she had broken through to a new level of visibility, with a host of high-profile commissions that seemed to arrive all at once.

A modern-dance choreographer drawn to dissecting conventions of ballet, Tanowitz began making dances in 1993, back when “what I do was not in style,” she says. In New York’s experimental dance scene of that time, where she got her start, “people weren’t necessarily pointing their feet and leaping and doing passés and things that I love. I just kept sticking to what I do.”

Her work

could be challenging for viewers, requiring an appetite for decisively nonnarrative movement and sometimes dissonant music. But it could also be exhilarating, brimming with invention on a small and large scale, from the position of a wrist to the interlocking geometries of an ensemble. While she earned a devoted following—and a Bessie Award for her 2009 Be in the Gray with Me—her admirers wondered why her work wasn’t more widely commissioned, especially by ballet companies claiming to champion innovation. (She was rejected five times from NYCB’s Choreographic Institute.)

In 2019, she seemed suddenly to be everywhere. Between May and October, she unveiled new works for NYCB (she credits the company’s new leadership for giving her a chance), The Royal Ballet and Ballet Across America at the Kennedy Center, where she made a joint work for Miami City Ballet and Dance Theatre of Harlem. That same year, she choreographed for two historic modern dance troupes: the Paul Taylor Dance Company and the Martha Graham Dance Company. And her own company made its international debut, bringing Four Quartets—rapturously received during its 2018 premiere at Bard College—to the Barbican Centre in London.

A less experienced artist might have been flustered by so many commitments—and so much attention—and Tanowitz admits that “it did feel like a lot, at a certain point.” But having been in the field for a while, she knew how to stay grounded, not losing sight of why she does what she does. “I just love the process,” she says. “I love being in the studio with my dancers, trying to figure out what to make.”

For Tanowitz, the dance studio has always been a kind of respite. Growing up outside of New York City, in Westchester County, she was not, as she puts it, “book smart.” She struggled academically. “I think, looking back, I did have processing issues and reading comprehension issues,” she says. “I wasn’t horrible. I just had to work really hard at school to pass.” But in dance class, which called upon other modes of thinking, she thrived. “I think that was part of my attraction to dance,” she says. “It was my way of sort of trying to fit in.”

She began taking classes—modern and jazz—in fourth grade, at the Steffi Nossen School of Dance, where she continued training through high school with teachers including Hannah Kahn and Kathryn Posin. In eighth grade, her mother signed her up for a dance intensive at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School, in the Bronx, where she studied with Blondell Cummings—her first improvisation class—and Ohad Naharin.

“I was terrified,” she says of trying to improvise. “But I did it.”

Erin Baiano, Courtesy NYCB

Though Tanowitz took ballet in high school and as a dance major at Ohio State University, it wasn’t the foundation of her training. “I think because I came to ballet late, I’ve always been interested in it,” she says. “I can’t do it, right? So I’m always asking questions. When I start working with ballet dancers, I’m like, How do you do this? What does this step mean? How do the mechanics work?”

In the summer before her senior year of college, Tanowitz attended the American Dance Festival, encountering new ideas that inspired her to more deeply explore her own. Immersed in dance from morning to night, she saw works by Molissa Fenley, Bill T. Jones and Paul Taylor, and took classes with Ishmael Houston-Jones, Sally Silvers and Mark Dendy, among others.

“That’s when I really got serious, and really felt connected to making work and being an artist,” she says. When she moved to New York after graduation, she quickly decided to focus on choreography rather than dancing for other people, partly because, by her own estimation, “I wasn’t a star dancer, at all.”

After a few years, Tanowitz enrolled in an MFA program at Sarah Lawrence College, hoping for an artistic growth spurt. “My work wasn’t really getting any better,” she says. One of her instructors was the choreographer and former Merce Cunningham dancer Viola Farber, who became a mentor to her. Tanowitz fondly remembers the advice Farber gave her when she landed one of her first shows, a split bill at Dance Theater Workshop. “She said, ‘Now don’t start making dances you think they want to see,’ ” Tanowitz recalls. “And I never did.”

While trying not to cater to outside expectations, Tanowitz sets a high bar for herself. “Every time I do a show, I try to up the ante on myself,” she says. Her self-assigned tasks don’t need to be elaborate to be generative. A few years ago, she noticed that she often relied on walking as a transition. In her next dance, walking wasn’t allowed. “I love limitations and rules,” she says (adding that most of the time, she breaks them).

To propel a new dance forward, Tanowitz often plucks material from her older works, finding ways to reimagine it. Melissa Toogood, who began dancing with Tanowitz in 2006 and is also her rehearsal director, describes her as “a master recycler” and an efficient editor. “If it’s not working for her, she’ll just scrap it and not look back,” Toogood says.

Toogood also danced for Merce Cunningham, to whom Tanowitz is often compared; the Cunningham technique, which prepares the body for brain-teasing coordinations, is integral to her work. But what the two have in common, Toogood says, is more about an attitude toward movement than about the movement itself. “Neither of them discriminates against movement. Nothing is silly; nothing is off-limits to try or experiment with or manipulate or look at again or analyze. It’s not like, ‘Oh, I would never do that move.’ They would both be like, ‘Okay, what can I do with that move?’ ”

Highly aware of her place in a modern-dance lineage, Tanowitz makes an effort to learn from older artists, sometimes by performing their work. In 2019 she danced in the Los Angeles version of Night of 100 Solos, the multi-city event honoring Cunningham’s centennial; the year before, she appeared at the Museum of Modern Art in a new iteration of The Matter, by the postmodern dance pioneer David Gordon, another of her mentors. “I don’t see myself as an individual choreographer doing my own thing,” she says. “I’m always thinking about where I fit in on a timeline, and that informs what I make.”

But what informs her most of all is more immediate: her day-to-day exchanges with her dancers, whose idiosyncrasies shape her work. “Ultimately, the dances I make are about the people in the room,” she says. Toogood notes that although Tanowitz is very much in charge as the choreographer, she gives her dancers space to be themselves. “As I evolve as a person, mover, performer, I’m able to do that within the work,” Toogood says.

That regard for performers as people comes through to an audience. “Pam works with very complex, interesting, deep dancers,” says Gideon Lester, the artistic director of the Fisher Center at Bard College, where Tanowitz is the first choreographer in residence. “They don’t hide behind the form of the work, but the work reveals to us who they are.”

In the past year, even under drastically altered circumstances, Tanowitz has allowed her usual compasses to guide her: pushing herself to try new things, focusing on process over product, and finding some humor in it all. (She’s as funny as she is hard-working.)

She has developed new partnerships with several filmmakers, including Jeremy Jacob, who teamed up with her on a short film for American Ballet Theatre (starring David Hallberg) and a playful digital companion piece to Finally Unfinished, a new work that was streamed live from The Joyce Theater. Interested in what film can do that live performance can’t, she’s been learning from her collaborators about the possibilities of the medium.

“The fundamental thing about Pam is that she’s curious,” Jacob says. “Her entry point into the world is curiosity.”

For the first time since the onset of the pandemic, Tanowitz has returned to making work for a live audience, with a new ensemble piece for The Australian Ballet set to premiere on April 6. But like the rules she sets for herself, the pandemic’s limitations have in some ways been fruitful. In Finally Unfinished, which repurposed choreography and costumes from her past works for The Joyce, the dancers ventured out into the theater’s vacant seats, roving among them in ways a live audience would have made difficult. The camera offered views not usually available from those seats, peering right over a dancer’s shoulder, or looking up on the red velvet curtain as it hurtled down toward the stage.

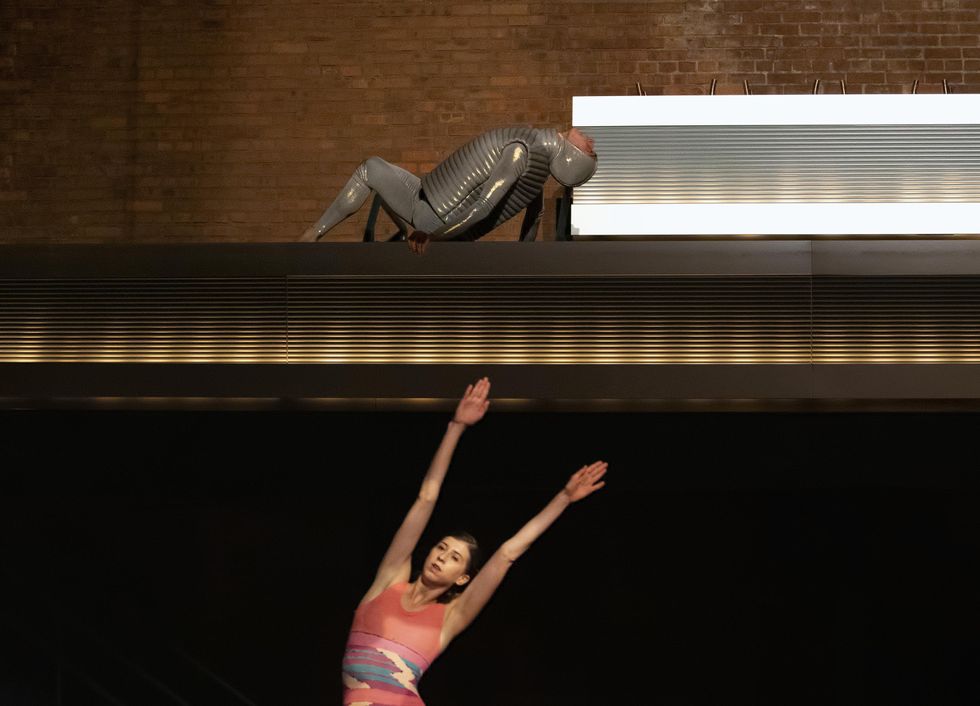

The costumes, by Tanowitz’s longtime collaborators Harriet Jung and Reid Bartelme, matched the theater’s materials: its zig-zaggy carpets, the brick of its upstage wall. Adding some mischief into the process, Jung and Bartelme decided to keep secret one of their new creations, a design for dancer Zachary Gonder.

Tanowitz says that normally she would have insisted on approving it, but in this new context, she agreed to be surprised. Revealed at a rehearsal, it turned out to be a shimmering, head-to-toe silver encasement, a kind of squishy suit of armor that blended with the balcony where Gonder danced. “It was great!” Tanowitz says, remembering how hard she laughed when she first saw it.

New conditions call for new forms of risk-taking, and Tanowitz is embracing them, keeping herself in a place of discovery. Playing it safe has never been her way, and the upheaval of the past year hasn’t changed that. As she says, “I would rather fail at something interesting than do something boring.”

Tanowitz’s Finally Unfinished

Erin Baiano, Courtesy Tanowitz

What Is Making a Dance?

After one of our interviews for this story, Tanowitz sent me an email with the question “What is making a dance?” in the subject line. I opened the message to find this list (or most of it; she added one item later), which distilled much of what she had told me about her choreographic process. Rather than excerpting it, I thought readers would like to see the list in full. It’s shared here with her permission.

- Inspiration and despair

- An exchange with the audience

- It stirs sensation and transcends anything that could be ascribed to a narrative

- Gaps between pauses

- A frame

- Never making what I want

- Desire to channel organization

- A way to harmonize with past masters

- My ideas get filtered through the lives of the dancers, and the more dances I make, the more I discover myself

- If I made the dance I carried inside me, that would be the last one.