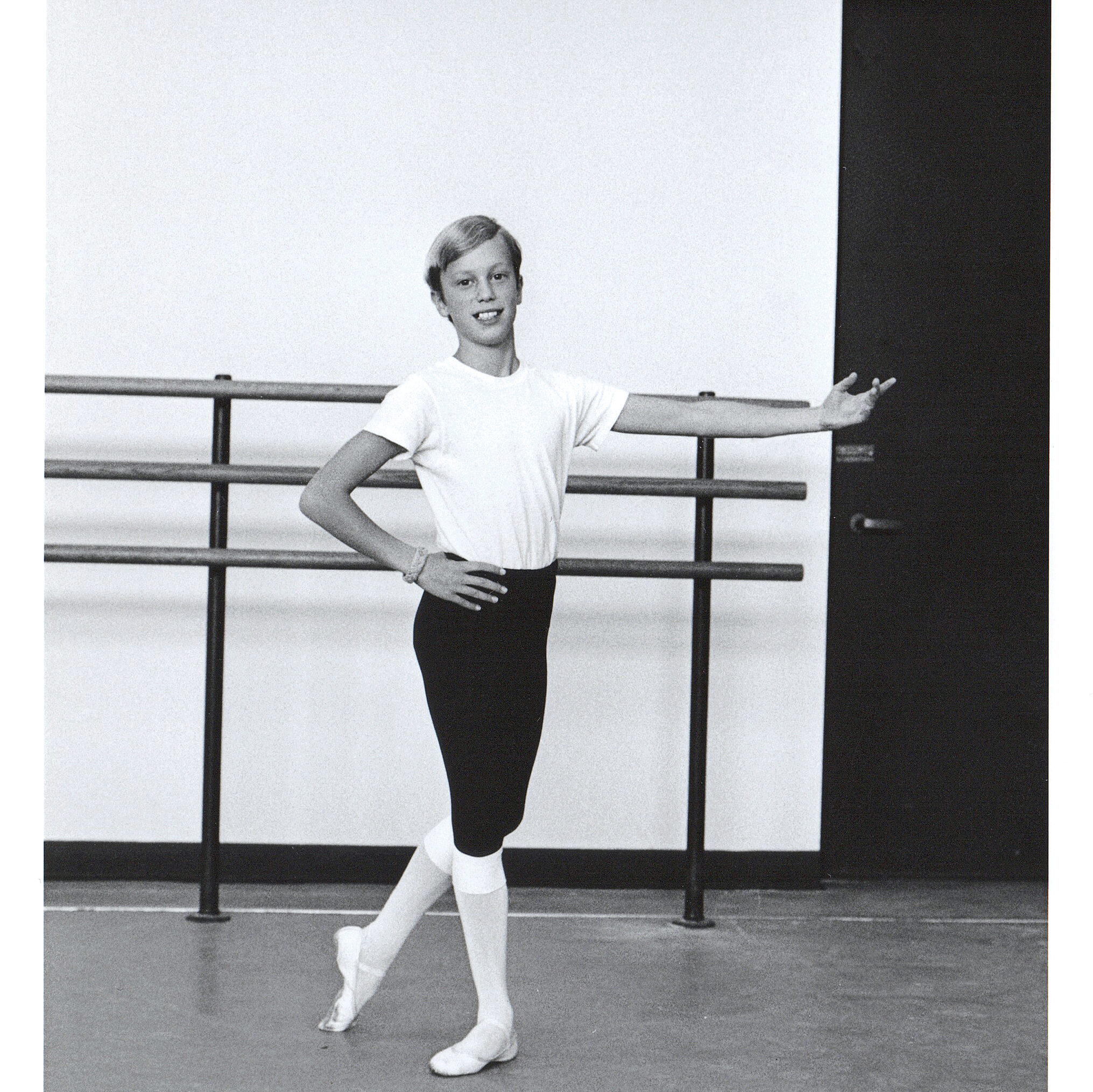

Dancer and Director Peter Boal’s Thoughtful New Memoir Considers the Childhood Turmoil that Would Shape His Approach to Dance

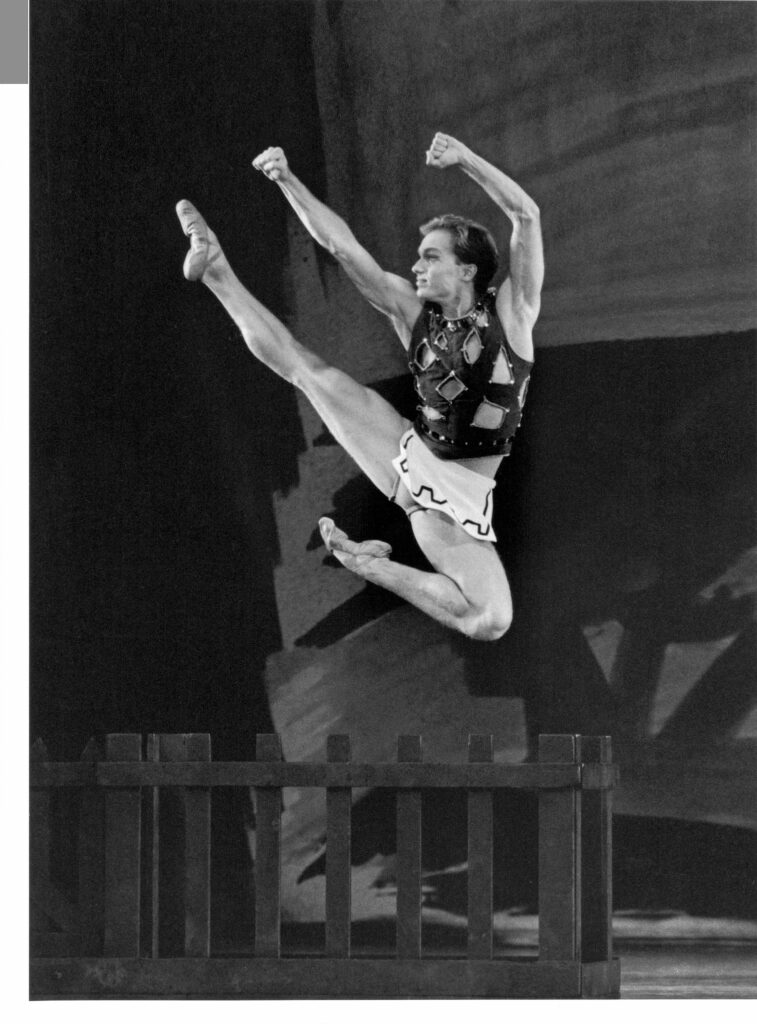

In his years at New York City Ballet, from 1983 to 2005, Peter Boal was greatly admired for the purity and elegance of his dancing. In that clarity there was something soulful and deep. It was as if, by doing the steps without adornment, he was revealing the truth they contained.

Later in his career, that technical and artistic integrity applied to his teaching, as well. Then, after retiring at 40, he became the artistic director of Pacific Northwest Ballet, a position he still holds. His leadership style, like his dancing, is calm, soft-spoken, and thoughtful.

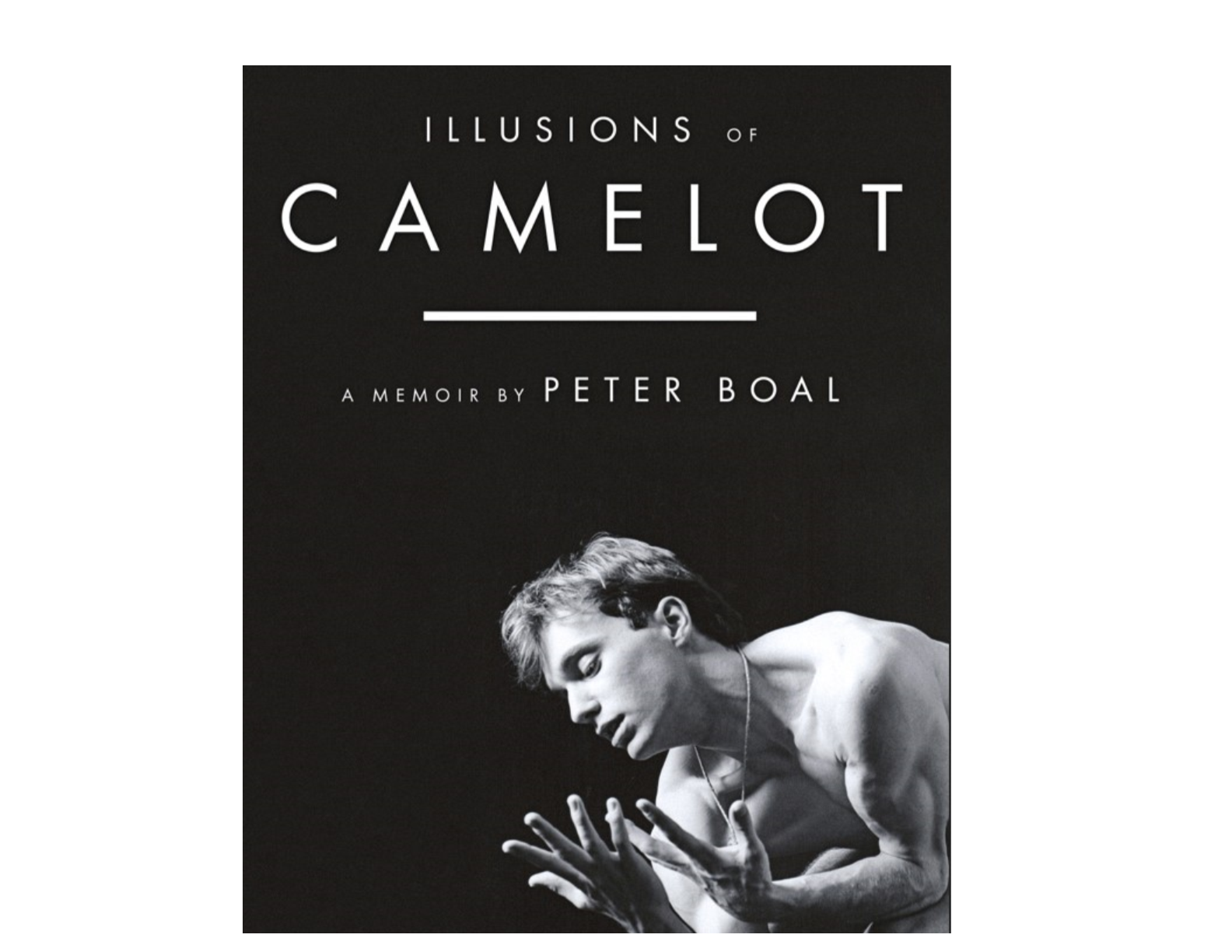

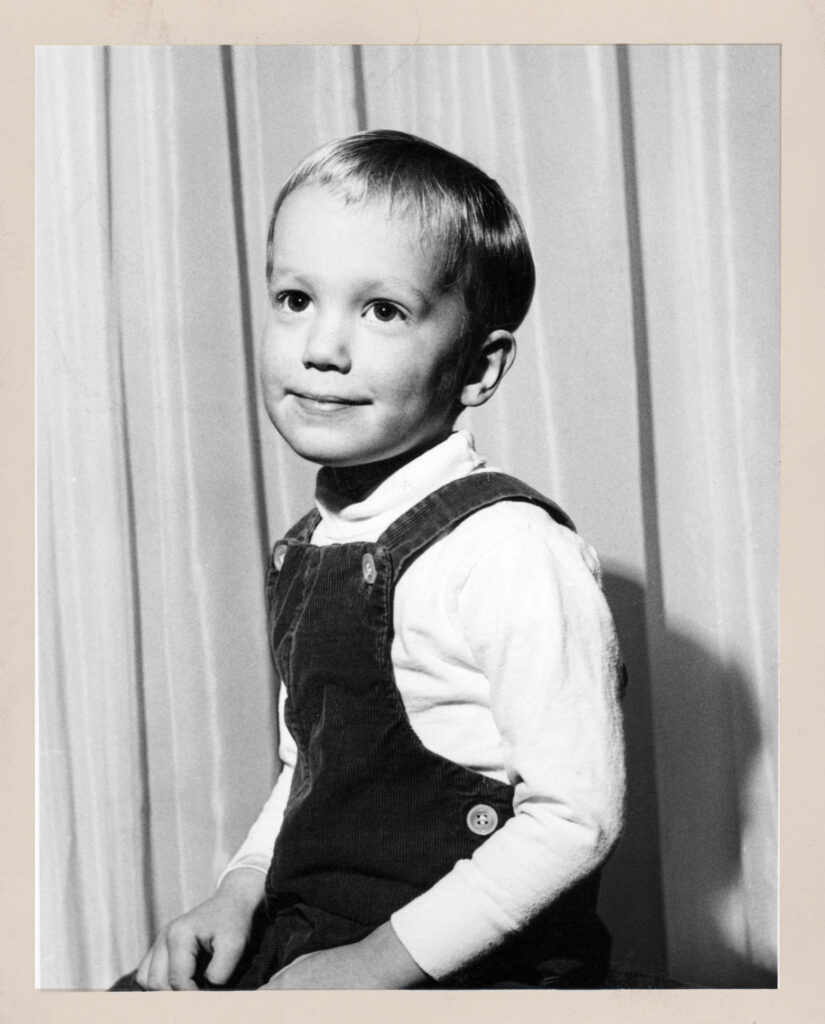

It’s no surprise, then, to discover that he is also a writer. This May, he published his memoir, Illusions of Camelot, with Beaufort Books. It contains a series of reflections on his childhood and adolescence in the wealthy town of Bedford, New York, and then, later, in New York City. Financially and socially, his was a comfortable childhood. But that idyll—the Camelot of the title—concealed a deep vein of turmoil. That contrast between appearance and experience is one of the main themes of his book.

Recently, we talked about writing, ballet, and his relationship to his past.

When did you start writing?

I started writing in grade school and enjoyed it and got some encouragement. But there just wasn’t time to write because of my work as a dancer and a director. I was one of the early ones at New York City Ballet to start taking college classes. I took a writing course with a man named Sidney Offit at The New School. One time, Sidney picked out a story I had written to read to the class, without saying who the writer was. It got such a strong reaction from the class—that was the first time I realized my writing could affect people so strongly.

This is your first book. How did it come about?

It was a long time coming. I first started thinking about it in 2013, writing down stories without knowing where I would end up. I knew I didn’t want to do a dance book. But [writer and friend] Leslie Tonner Curtis told me, “You really should add in some stuff about dance.” Still, 80 percent of the book isn’t about dance at all.

In the book it’s clear that you had a lot of unfinished business from your childhood, including the need to reflect on your father’s alcoholism and his death when you were still very young.

Yes, I don’t think I’d ever really thought deeply about his death. I sort of moved on. Writing the book was a way to return to that experience and travel through it in a more adult, rational way than I could when I was a child. I had come to realize the love between us was so strong that it had remained with me, and that the resentment I had felt because my father wasn’t there and couldn’t meet my kids or my wife was secondary. I realized it was hard for him to give, but what he had given me was meaningful and stayed with me.

You write about your relationship with John Bass, a fellow dancer who died of AIDS in the mid-’80s, when much about the disease was still misunderstood. Does it feel hard to have something so private exposed for all to see?

It does now, because I’m a pretty private person. I never hid anything, but I didn’t talk about things. Kelly [Kelly Cass, Boal’s wife of 31 years] was in the company at the time, and we were friends, but I didn’t tell her I was going through this very difficult time. That’s who I am, strength or weakness. I was a dancer in a 110-member company, with a boyfriend. Everybody knew—people came to the funeral. It’s just that people haven’t been discussing Peter Boal’s romantic life for the last 40 years.

What role did ballet play for you in the midst of these very difficult experiences?

Other people have their churches or their Quaker meetings, but for me, taking Stanley Williams’ class, with its white walls and simplicity and the focus of silence and music, was this place of clear-mindedness and beauty. I had that for an hour and a half each day my entire life.

It seems that you took to ballet from the very beginning. Was that facility you had part of the pleasure of it?

I did enjoy being good at it. And it put me in the proximity of people like Nureyev [who used to take Stanley Williams’ class]. We would talk about Stanley’s technique during barre. It was so uplifting. You can criticize many aspects of New York City Ballet at the time, but it was a wondrous world to exist in, a wonderful world to escape to. It plucked me out of the not-so-healthy environment of my town and my family.

Sometimes your childhood in wealthy Bedford, New York, sounds like a Cheever story, with all the mansions and golf clubs and partying. Especially the drinking. What role did alcohol play in your life growing up?

It was a constant. I remember being driven home at night from a friend’s house and seeing cars veering all over the road. I know my dad was pulled over many times. When I was 10, I snuck downstairs to drink bourbon. As a kid, you want to do what your parents do. I thought I needed to do that for some reason.

You touch on issues of race and class through the prism of your relationship with Hattie Lindsay, the Black housekeeper who worked for your family. How did you perceive your relationship with her as a child?

In a way, Mrs. Hattie almost singlehandedly did the job of raising me. I never wanted to leave her side. Most of what I needed to know in life came from Mrs. Hattie before the age of 10. She stopped working for us when I was 10, but the relationship continued until she passed, when I was 16. It was a beautiful friendship. Mrs. Hattie didn’t talk much about race, even though she was a very strong-willed person. But I could feel the racial dynamics in subtle ways. I wish we had engaged more deeply during those years on the topic of race, but by then my head was in the clouds with my ballet training and living in New York.

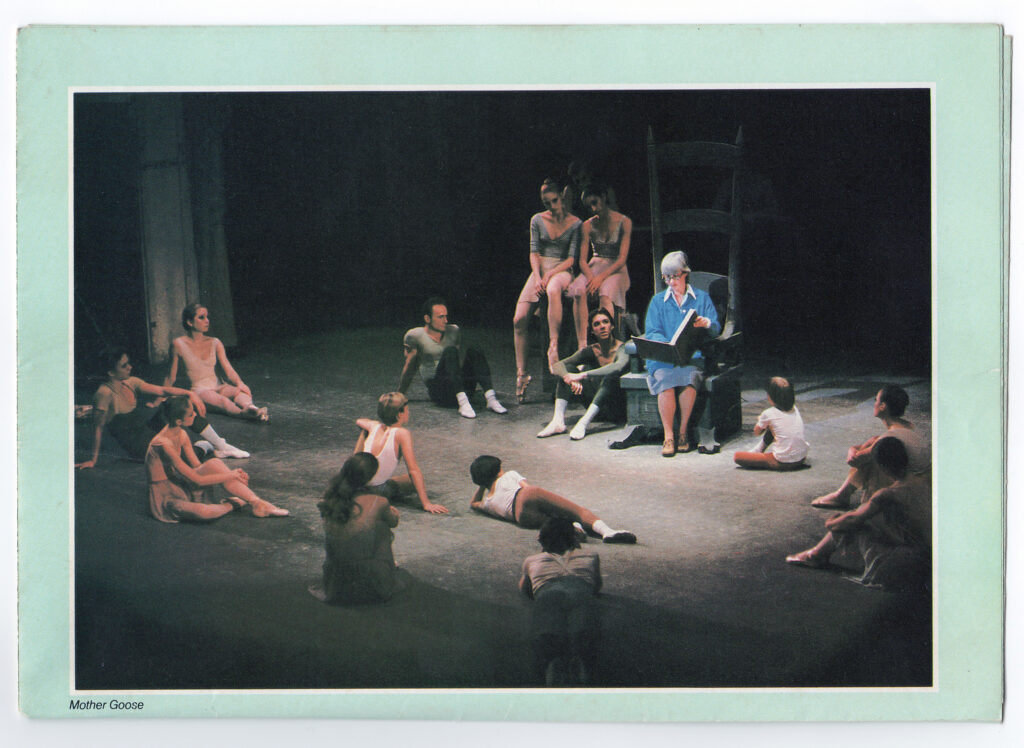

Other figures who play important roles in the book are Jerome Robbins and Stanley Williams. Were they, in a way, father figures?

I didn’t think about it before I wrote the book, but now I see there was this pattern of generous older men who served in a teaching and perhaps fatherly capacity. For me, Stanley’s class was a temple. We didn’t have a friendship outside of the ballet studio, and yet we had such a close one in the ballet studio. And with Jerry, he used to like going into a studio with me to work on ballets he was choreographing, even ones I would not end up dancing in. I could see his frustrations and tried to help him in any way I could.

What do you feel you learned about yourself through the process of writing this book?

In part, I did it in order to see if I could, and to see how much honesty I could put into my writing. Writing is a means of expression. If I could play the violin beautifully, I would do that. Dancing, for me, was an outlet for expression, a deeper dive into emotions.