African-Arts Scholar Robert Farris Thompson Dies at 88

Robert Farris Thompson, who was given the Outstanding Contribution to Dance Research award by the Congress on Research in Dance in 2007, died on November 29, 2021, at 88 years of age. Thompson was the Colonel John Trumbull Professor of the History of Art and, from 1978 until 2010, Master of Timothy Dwight College at Yale University. He’d been on the faculty since 1965.

“Who is this man?” I thought when I first met him. It was around 1974, and I was dutifully cataloguing slides at the Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives in the National Museum of African Art as a young master’s student and new archivist. He rushed into the room, gasping at images of Africa and, awe-struck by everything he saw, exclaiming in Yoruba, complete with expletives, wild with enthusiasm, and finding gold mines of evidence everywhere. I was a student of dance and art, with pretensions of becoming an art historian, and a few years later, the head of my dance department, Shirley Wimmer, called me up with great excitement, saying she had just heard a lecture by Robert Farris Thompson, and knowing my desire to get into African art, she said, “You have to go to Yale.”

Robert Farris Thompson was a legendary professor of the history of art in Africa and the African diaspora in the Western hemisphere and throughout the world. Yale University was his home throughout his adult life, and Thompson and Yale have been synonymous for thousands of Yale graduates for a half century. From Yale, he received his BA in 1955, his MA in 1961 and his PhD in 1965. He studied for the doctorate under Professor George Kubler, then a specialist in Spanish art. But his heart was in African-American and Latin-American culture. His dissertation fieldwork was conducted among the Yoruba in Nigeria. He began teaching the history of art in 1961. His undergraduate course, From West Africa to the Black Americas: The Black Atlantic Visual Tradition, was considered part of the tradition for any Yale College student. From 1978 to 2010 he served as Master of Timothy Dwight College, the longest run of any serving master. TD students revered him as “Master T,” and the college produced sweatsuits showing a caricature of Thompson as a muscular bodybuilder, with the word “ashe“—the Yoruba term for “inner power.”

Probably his most pivotal piece of writing was the article in which he explored “An Aesthetic of the Cool,” appearing in African Forum, in 1966. Thompson was known internationally for his continually groundbreaking publications, beginning with the catalogue for an exhibition at UCLA based upon his PhD dissertation, entitled Black Gods and Kings: Yoruba Art at UCLA (1971). In 1974, UCLA and the National Gallery of Art sponsored an exhibition that revolutionized thinking about African art and culture, with a book entitled African Art in Motion: Icon and Act in the Collection of Katherine Coryton White. Again, for an exhibition at the National Gallery in 1981, he published, with Joseph Cornet, The Four Moments of the Sun: Kongo Art in Two Worlds.

In 1984, drawing upon his decades of lecturing on the arts of Africa trans-Atlantic world, he published one of the most influential works on the continuity of African art in the new world, entitled Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy. It was as much a praise song to African-American culture as an extensively researched, groundbreaking work of scholarship. His Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and the African Americas, in 1993, for the Museum for African Art in New York, accompanied the exhibition that traveled around the world to great acclaim as an examination of ensembles of sculpture never before considered by art historians.

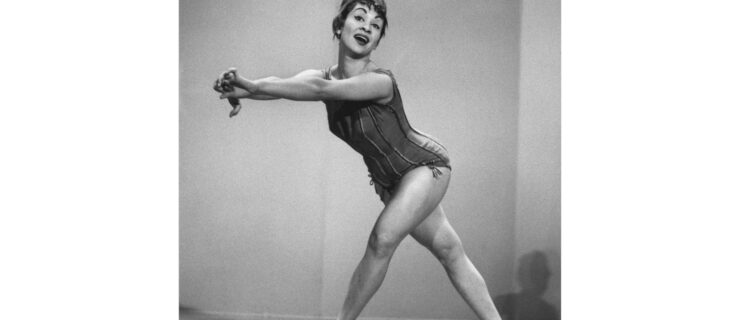

Thompson was born on December 30, 1932, to a wealthy El Paso, Texas, family: Son of Dr. Robert Farris Thompson, a surgeon, and Virginia Hood Thompson, a patron of the arts, he received a patrician education, attending secondary school at Phillips Academy Andover in Massachusetts, before admission to Yale. But he was anything but orthodox, despite his tweed sports coats and penny loafers. As a Yalie, he would slip out of New Haven and go down to New York City to the smoky Black jazz clubs, where he got to know all the early jazz greats. He started out, after getting his BA in 1955, traveling to Paris, with the hope of becoming a jazz player. He later championed such musicians as Tito Puente and John Coltrane. His earliest article was on Afro-Cuban dance and music, published in 1958, followed by another in 1961 on African music. He wrote a book on tango, and his last teaching years were devoted to his course New York Mambo: Microcosm of Black Creativity.

He was a fearless investigator, going deeply into the most difficult places, right into his 80s, and urged his students to be “guerrilla scholars”—that is, to totally embed and immerse ourselves within the society and culture we’ve chosen to study, to take great risks and endure pain, and to battle established misconceptions. He unapologetically practiced “advocacy scholarship” with a profound love and empathy for the people he studied. He felt a moral imperative to bring African and African-American philosophy and wisdom to the world, and to expose stereotypes. “That’s a pile of horsegeschichte,” he would say as he confronted and challenged the field of traditional art history passionately and always with great wit.

His art history was published in the traditional academic venues, but also in The Village Voice, The Fat Abbot, Rolling Stone and Saturday Review. He was recognized by the Arts Council of the African Studies Association with its Leadership Award in 1995. He was awarded the College Art Association’s inaugural Distinguished Lifetime Achievement Award for Art Writing, in 2003, and was named CAA’s Distinguished Scholar in 2015. In 2021, Thompson was awarded the honorary degree—his fourth Yale degree—Doctor of Humanities, by the president of Yale University. The College Art Association aptly described him as a “towering figure in the history of art, whose voice for diversity and cultural openness has made him a public intellectual of resounding importance.”

Long before “globalism” was even a word, he was preaching it in his classroom. The first day in class, the students were shown a slide of the world which Thompson zoomed in on until he reached Tokyo, Japan, and this was his springboard to upset all the preconceived notions about a bounded and traditional Africa. If he could find Africanisms in Japan, it was not such a leap to the Americas. He coined the term “The Black Atlantic.” Thompson’s persistent theme was that America—all America—is more African than it thinks.

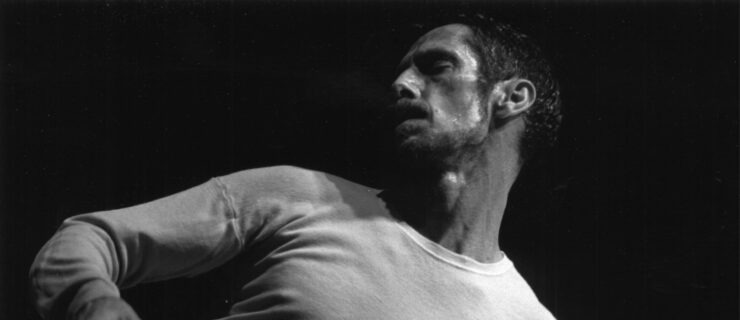

Virtually no one who sat through a Thompson lecture ever forgot it. It was an extravaganza of masterful drum playing, dance, song and all the poetry and cadence of a Southern preacher in the Black church. His performance never diminished—even when he was stuck in a little seminar room with three of us graduate students around a table, our jaws dropped to the floor. He would assign us readings in any language. (You don’t read Dutch? Get a dictionary.) He would punctuate his lectures with Haitian Creole, French, German, Hebrew, Italian, Kikongo, Portuguese, Spanish, Yoruba and other languages, without translation. He once told me the secret to his success: “I am shameless.” His Kikongo wasn’t perfect, and he didn’t have a dancer’s body, but he never let that stop him from going full-out to learn every tango and mambo dance step, every multimeter rhythm, every chant and praise song that he could. He didn’t care if you liked it. He liked it, and that was abundantly obvious as he reveled in all that he did.

Bob will be greatly missed by his dozens of Yale protégés now prominent in the fields of African and African-American art, thousands of Yale College graduates, and the world of lovers of African and African-American music, dance and art. A memorial service will be held in the spring of 2022 at Yale University. —Frederick John Lamp