Is Instagram Changing The Dance World's Value System?

The entrancing power of Instagram can’t be denied. I’ve lost hours of my life scrolling the platform looking at other people documenting theirs. What starts as a “quick” fill-the-moment check-in can easily lead to a good 10-15 minute session, especially if I enter the nebulous realm of “suggested videos.”

My algorithm usually shows me professional ballet dancers in performances, rehearsals, class, backstage and on tour, which I quite enjoy. But there are the other dance feeds that I find myself simultaneously intrigued and horrified by: the hyper-elastic, hyper-extended, gumby-footed girls always at the barre doing developpés to six o’clock. There are the multiple turners, the avid stretchers and we can’t forget the endless balancers.

This parade of tricksters always makes me wonder, What else can they do? Can they actually dance?

I often click into these accounts just to see what else there is—maybe the flexi-girl has real talent and technique. Unfortunately, there usually isn’t much more to see. The super gumby girl is perpetually stretching, the turner has endless clips of pirouettes (often to same side and out of the context of a combination) and the girl with the crazy arched feet is always tenduing and “pointe shoe modeling” (at the barre).

As I hunt for signs of real training and artistic quality, I find myself sliding into a virtual Insta-K-hole, ending up a bit confounded and depressed.

Social media is a space where the extremes of almost anything (beauty, physique, lifestyle) are celebrated and held as aspirational, resulting in a growing lack of appreciation for the simple or average. In dance, the “average” or “simple” amounts to clean, solid technique, or a body that is well-formed and capable, or a beautifully-placed 90-degree arabesque. Everything has become so extreme that if it’s not 15 after 6 o’clock or eight turns, it is of no interest.

This is a slippery slope. Surfing Instagram is like watching the virtue of dance as a high art deteriorate in real time. Who and what goes viral is a reflection of a newly-forming value system. With each “like” and “follow,” we vote on the future of our field.

It’s Not Just Harmless Visual Candy.

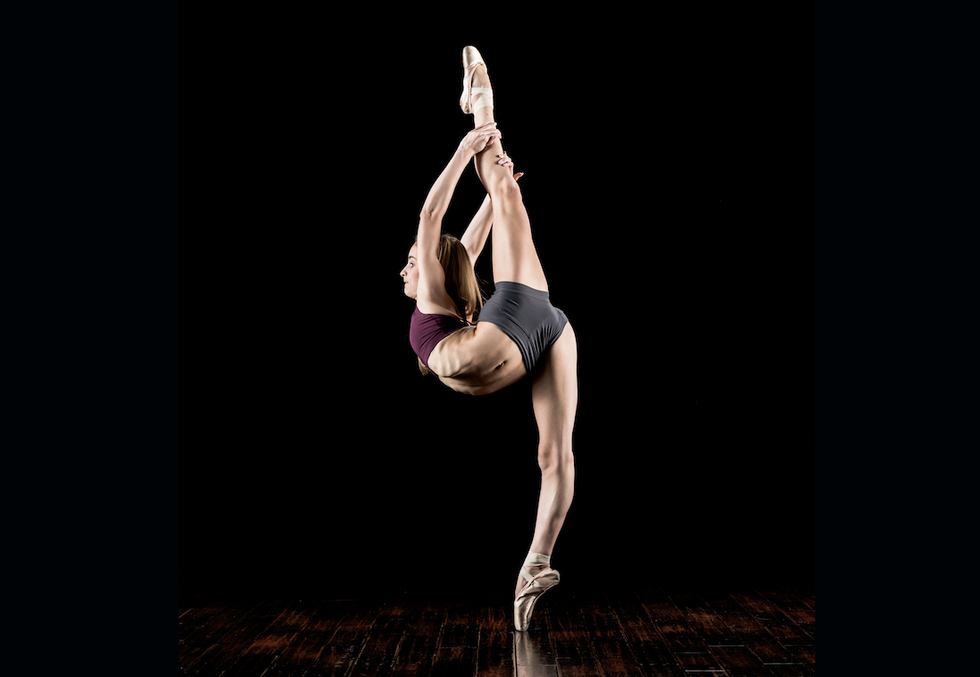

Tricks may be impressive, but dance is about more than contortions. Photo by David Hoffman/Unsplash

Tricks may be impressive, but dance is about more than contortions. Photo by David Hoffman/Unsplash

These sorts of IG accounts are basically dance erotica, where the physical attributes coveted by dancers are fetishized, presented in such extremity that they border on grotesque, unrealistic and—more importantly—often unuseful. When dance lovers (whether they’re educators, students or directors) indulge in the reduction of our art to human caricature and tricks, turning the elite forms of line and grace into a Vaudevillian sideshow, the real danger is the effect on our sensibilities.

What seems like harmless visual candy is setting new standards for young dancers as they seek to emulate their Insta-heros, and “likes” are validation.

Think about it: How often do young dancers go to the theater to actually see live dance? This generation’s primary experience of dance is via an electronic device (television, tablet, phone). They experience a one-dimensional, truncated version of dance, viewing snippets and clips of full pieces, and with diminishing attention spans. If anything over four minutes is too long, what does that do for a three-act story ballet?

Often, dance students’ first contact with principal dancers is via their ‘Gram. Though these stars might have lengthy careers with weighty achievements to their credit, young dancers often rate them as equal to tricksters with thousands of followers.

The Double-Edged Sword of Insta Opportunities

You can’t hide your technique once you come out from behind the camera. Photo by Suhyeon Choi/Unsplash

You can’t hide your technique once you come out from behind the camera. Photo by Suhyeon Choi/Unsplash

Having an outsized level of visibility can earn these Insta-stars money, as they get sought by dance organizations and other brands to become “ambassadors.” Which is all well and good. Any way an artist can find ways to earn extra money is a win.

But these brands are contracting influencers, not necessarily dancers; they could have two left feet and 500,000 followers. The ability for those new sensations to monetize their popularity has destabilized the already compromised foundation of dance’s value system. More and more, we hear about students being “discovered” on Instagram and courted by serious schools.

You could argue that this levels the playing field since now anyone from anywhere can be offered an opportunity. But is this an authentic gauge of talent? Everyone’s feed is edited and curated—no one is posting videos of things they can’t do well. When you see that student in a technique class the truth is revealed: she can do that turning diagonal but ask her to stand on one turned out leg, and the jig is up.

One professional black ballet dancer who aggressively worked to increase her followers a couple years ago got a great deal of press, was courted by brands and became somewhat of a face for black ballerinas. However, a source informed me that when several of her followers came to see her perform, they were less than impressed and unfollowed her.

While a picture might be worth 1000 words, it is not worth 1000 steps.

Students Now Demand To Be Taught Insta-Worthy Tricks

Building the strength for a dance career requires more than learning pyrotechnics. Photo by Frederik Trovatte/Unsplash

Building the strength for a dance career requires more than learning pyrotechnics. Photo by Frederik Trovatte/Unsplash

Though most schools won’t admit it, having Insta-celeb attend your summer intensive or year-round program and post about it is free advertising. However the knife cuts both ways. Insta-star followers may want study where their idols train, but they also want to learn to do what they see on their feeds. Young dancers are “customers” and teacher/studio owners can feel pressured to give them what they want lest they go elsewhere.

These tricks, in and of themselves, are not bad things. However, devoid of a codified technical progression, which builds the steps incrementally, they can be disastrous. Dancing happens in the transitions, in the pathways. The foundation of technique is in the “how” steps are entered and exited.

When you teach with the focus only on the height of the leg, the number of turns or intricacy of a big jump, you are building a house of cards. It can be hard to convince a generation that has been raised on instant gratification that slow progress is well worth the time. Too many young dance students want to be “famous” more than they want actual careers in dance.

Social Media Fame Can Impact Real-World Decisions

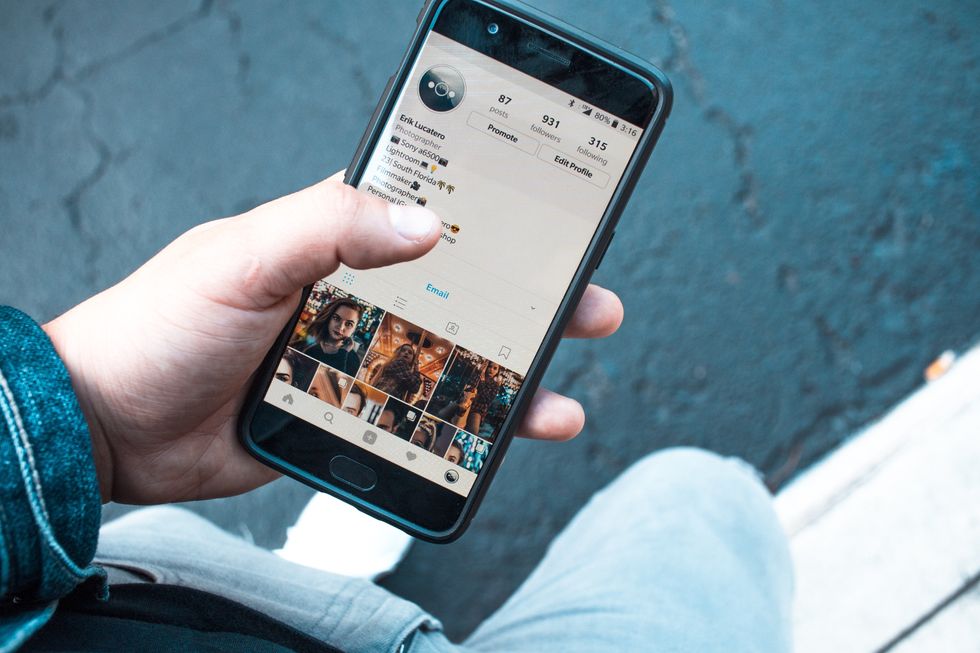

Should followers be able to determine casting? Photo by Erik Lucatero/Unsplash

Should followers be able to determine casting? Photo by Erik Lucatero/Unsplash

Amassing followers can translate not only into dollars through brand endorsements and sponsored posts, but we are beginning to see its results in ticket sales.

A dancer with avid followers can post their performance schedule and fans will…follow. When a professional dancer’s social media presence can attract attention to a company in ways that an expensive marketing campaign can’t, one has to wonder if this new influence could act as leverage for casting and ranking? You better believe that when ticket sales spike, the head office will notice.

But if casting is driven—or at least influenced by—social media popularity, what happens to the craft? What happens to the actual artistic standard of a company? Are we soon to see a company using an Instagram poll to give followers the opportunity to vote on casting?

All attention is not good attention, appropriate or for that matter, authentic. There was a time not so long ago when professional dancers and students alike had to have official authorization before engaging with the “press.” Today, every social media account is technically a press outlet. You can’t prevent people from posting about their lives. Some organizations have begun to include social media clauses in contracts, but it is a roller coaster–sized learning curve that we are all strapped into. It’s daunting; careers are just as quickly ended as begun on social media with a simple click.

About Those “Inspirational” Accounts

Since Instagram is a research resource, bad technique can have real consequences. Photo by Krys Alex/Unsplash

Since Instagram is a research resource, bad technique can have real consequences. Photo by Krys Alex/Unsplash

I would be remiss if I did not mention the badly-curated “inspirational” accounts started by well-meaning dance lovers who have less of a discerning eye for the dance aesthetic. My eyes have been continuously assaulted by images of dancers who have stripped down half naked in public risking life and limb to get a shot.

It’s like a Dr. Seuss picture book—on a bus, on a train, on a bridge, boarding a plane—with every post hoping to garner more followers, or better yet, go viral. Some are taken by professional photographers, others by peers and parents. The results run the gambit from artistically awe-inspiring to simply awful, with questionable quality and taste levels.

Inspirational dance accounts in a sense democratize dance with the premise that everybody can dance. Which is true—it would be folly to disregard that fact that dancers come in different calibers. But when skimming through feeds devoted to inspiring young dancers of color to study ballet, I find myself conflicted. Seeing young brown ballet students wearing a tutu creeping up, bent kneed on a toe shoe makes me wonder what are we trying to have them aspire to?

Although the intention is heartfelt, the execution can be…questionable, and frankly dangerous. Inspiring young dancers of color is necessary but so is establishing standard of excellence that aligns with the professional field.

Think it doesn’t matter? Instagram has become a research resource for fashion, television and more. Images for storyboards are pulled from the ‘gram. Advertisers think they can pop a pointe shoe on an average underweight model have her make shapes referencing passé or arabesque and have her read as “dancer.” (Remember the Free People ad, or Vogue‘s editorial with Kendall Jenner in pointe shoes?) When your art looks commonplace, people will believe that a pedestrian can do it, that there is no training or skill involved.

Honestly, We All Fall for It

Even the most curmudgeonly among us are wowed by what we see online. Photo by David Hoffman/Unsplash

Even the most curmudgeonly among us are wowed by what we see online. Photo by David Hoffman/Unsplash

Even the advocates of technique and artistry get wooed by the siren’s song of an S-shaped supporting leg, or the gravity-defying pyrotechnical jump that we really have no name for but wish we could watch in slo-mo so that we could figure out how it’s done. It’s a guilty pleasure that dance folk of a certain generation would be slow to admit to.

Teachers who admonish the flexible girl for stretching all the time instead of working on strength, and then tell the turning boy that “it’s not about quantity but quality” can easily be seduced by a 6 o’clock grand rond de jambe.

But dance educators would be wise to think about what they are posting, re-posting and co-signing with “likes.” You can’t tell your students it’s not about high legs on Monday if you are reposting the rhythmic gymnast-like dancer’s developpé pic on Sunday.

I Know Change Is Inevitable, But I’m Still Questioning It

What will we lose if we let our values disappear? Photo by Ryan Jacobson/Unsplash

What will we lose if we let our values disappear? Photo by Ryan Jacobson/Unsplash

As the world—and with it my field—is evolving, I relish the sweetness of the particular era when I was dancing (we all tend to be partial). I do not see change as negative, however with every iteration we gain and lose. I suppose I question: Can we control what we lose? In the shifting universe, can we as a community decide what is of such value that we preserve it? What is worth fighting for?

As a community, we would be remiss not to take a good hard look at how social media is changing the landscape of our field. As history has taught us, things once abandoned are hard to reclaim.