Top Broadway Choreographers on Bob Fosse's Legacy

Conscientious theatergoers may be familiar with The School for Scandal, The School for Wives and School of Rock. But how many are also aware of the school of Fosse?

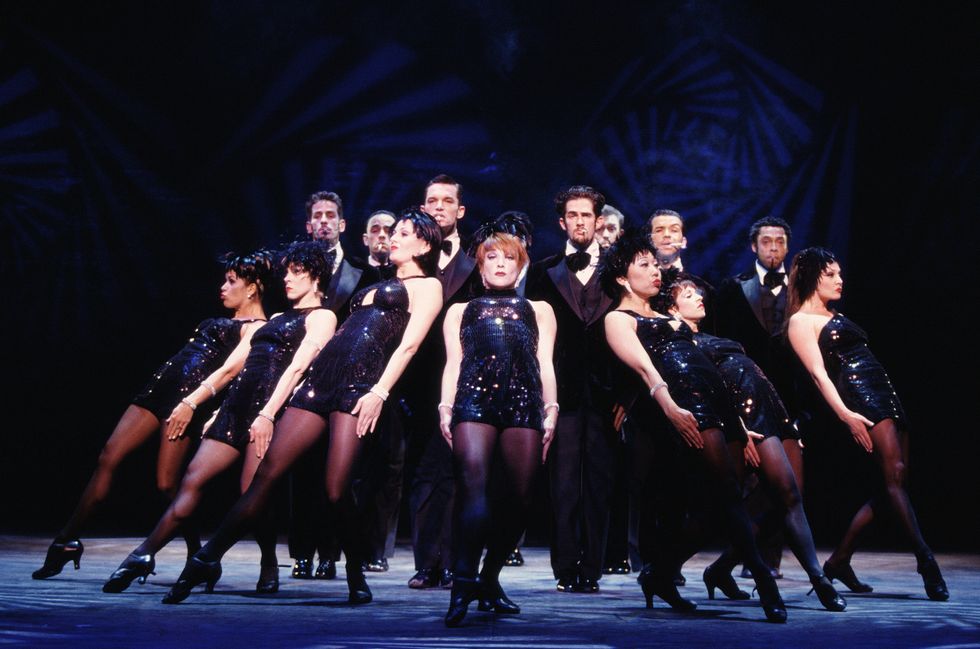

The 1999 musical, a posthumous exploration of the choreographic career of Bob Fosse, ran for 1,093 performances, winning four Tonys and 10 nominations; employing 32 dancers; and, completely unintentionally, nurturing a generation of Broadway choreographers. You may have heard of them: Andy Blankenbuehler and Sergio Trujillo danced in the original cast, Josh Rhodes was a swing, and Christopher Gattelli replaced Trujillo when he landed choreography jobs in Massachusetts and Canada. Blankenbuehler remembers that when Trujillo left, “It was as if he was graduating.”

Like the others, Trujillo didn’t appropriate the distinctive Fosse style. But it’s more than happenstance that the show produced this bumper crop of choreographers. Ask them why, and they make the school analogy. Trujillo says, “We all need some sort of master, like Michelangelo was. And for us, to be able to experience the work of Bob Fosse was like going to graduate school in choreography.” Blankenbuehler likens it to “a finishing school.”

For Rhodes, it was more like his freshman year—Fosse was his first Broadway show, and he was totally focused on performing. But, he says, “Even if you didn’t know you were going to be a choreographer, that kind of training is like having a professor help you along the way. We all had Professor Bob Fosse.”

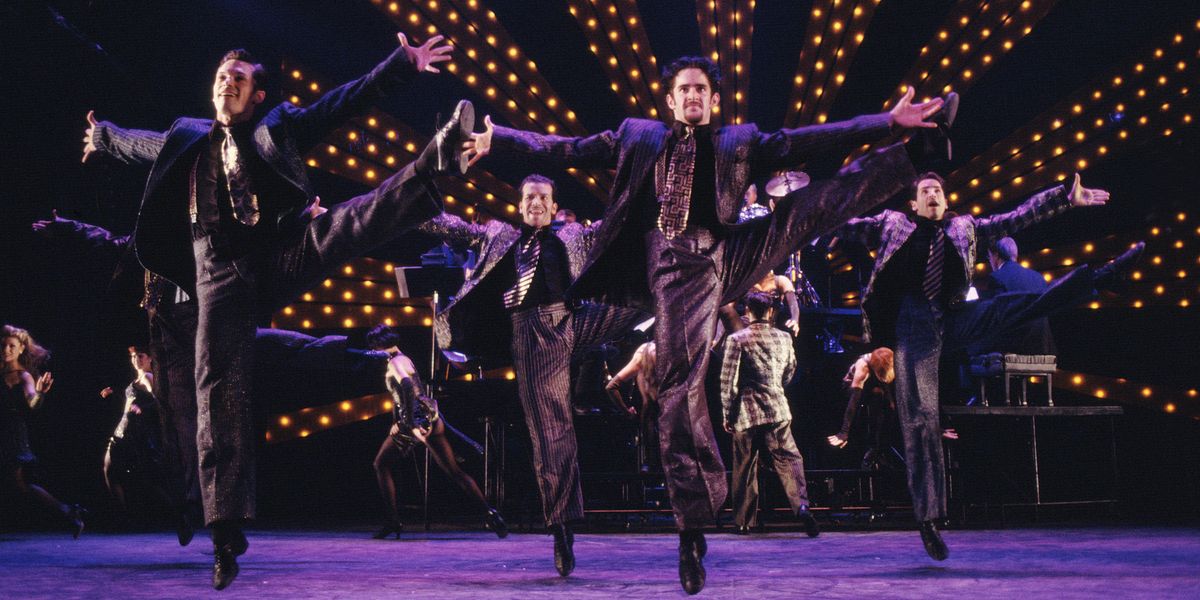

Joan Marcus

They needed him. As Blankenbuehler points out,“There weren’t a lot of mentors.” Partly because of the impact of AIDS, partly because dance shows were not in fashion in the ’90s, there wasn’t “a Bob Fosse or a Jerome Robbins or a Michael Bennett I could chase—who I could dance for in his shows, be his dance captain.”

He learned a lot doing several shows with Susan Stroman, Blankenbuehler says, but he was still “attracted to the classics—to study from them, as if they were a teacher.” That’s why, although already a choreographer, he returned to performing to tour with West Side Story. “I’d never done West Side,” he explains. “To me it was like a college course. And I think dancing in Fosse was very much the same thing.”

Rhodes notes that doing the show was not for everyone. “You had to be really dramatic with your body; you had to tell a story; you had to show musicality. And you also had to have a certain type of performance quality. I think all those things are sort of beyond just average dancers—maybe that is what gave us all insight into how far you can take dance, and how much you can tell a story with dance.” For him, the crucial lesson was Fosse’s composition, “the way transitions happen, the way you get from one formation to the next. He had meticulous composition—it was like Balanchine.”

Rhodes says composition was his takeaway, “probably because as a swing, you have to attack not just the step and the style. You have to understand the entire stage picture. So at a very young age, I got the master class in the overall picture of Fosse’s work. I got to watch it and learn what worked. As I put myself into all these different roles, I had to find the way in that was right for my body. I didn’t realize it at the time, but being a swing was actually preparing me to be a choreographer.”

Now, he says, when he’s stumped, he finds himself borrowing from the numbers he did in Fosse. “It turns into different steps, because it’s a different show with different characters,” he says. “But Fosse’s composition will always get you out of a jam.” A particular favorite, he says, is “Rich Man’s Frug,” with its interweaving clusters crossing and circling one another. “It works like a Swiss clock,” he says. “That kind of composition is beyond steps or the style of the movement.”

Blankenbuehler looks beyond the steps, too, beyond the isolation that is such a crucial element of the Fosse style. “Another part of isolation,” he notes, “is stripping down the unimportant. A lot of Broadway musicals are actually about adding on. That’s not a bad thing, but Fosse’s way is a different approach. You strip away, and boil down what’s most important. ‘Big Spender’ is a perfect example—he stripped everything away to its raw, cold bitterness.”

The Hamilton choreographer also cites Fosse’s “study of tension and conflict, because so much of his choreography is about not letting out energy—the internalization of deeply seated pelvic angst. It feels sexual, but it’s really about neurosis and dysfunction.”

The climax of Hamilton, he says, the slow-motion Bullet dance that kills the title character, is “a Fosse-esque gesture”: not in its steps, “but in the way it constricts energy and boils down one statement into a moment in time. And that’s what I learned at finishing school.”

When Blankenbuehler and Trujillo toured together in Fosse, Blankenbuehler recalls turning their 10-minute breaks into study sessions: “We would sit outside and write notes on the show—analyze the show, talk about our thoughts about the show.” He’s held on to that notebook. And, he says, he recognizes the same impulse in some of his casts. “I know who’s a choreographer—you can see their brain working in those ways. It’s a gift for me, because I know I have somebody who’s using their brain first, not just their body.”