What Does Fair Pay for Dancers Actually Look Like?

The dance field isn’t immune to the “gig economy” that’s disrupting everything from buying groceries to getting a ride to the airport. “We’re seeing more people identify as freelance dancers, and more people deciding not to start their own companies, because they’ve seen how that model works or, rather, doesn’t work,” says J. Bouey, dancer and founder of The Dance Union podcast. “Even major companies are hiring more often from project to project.”

At the same time, the cost of living continues to skyrocket in dance capitals like Bouey’s Brooklyn. So it’s no surprise that artists feel anxious about making ends meet. But this can also be an opportunity to discard old ways of doing business. “We’ve made gains, at least in terms of people recognizing what their pay should be,” says Lisa Davies, a former rehearsal director at Les Grands Ballets Canadiens de Montréal who, five years ago, founded the organization Danse à la Carte, which supports Montreal artists. “I never had the level of comfort dancers have today in discussing payment with their employers, even in my full-time jobs.”

J. Bouey points out that today, even some major companies work on a project-to-project basis.

J. Bouey points out that today, even some major companies work on a project-to-project basis.

David Gonsier, Courtesy J. Bouey

Three movements towards fair pay in dance have gained the most traction:

Unionization

For Griff Braun, director of organizing and outreach for the American Guild of Musical Artists, the primary issue is lack of leverage. “You’re not going to get a lighting designer without a certain amount of money. You’re not going to get a theater unless you’re able to pay the rental fee. But there’s no floor for the artists onstage.”

Beginning last July, Braun has been convening freelance dancers based in New York City and Chicago to brainstorm what unionization might look like, whether or not they end up alongside the 24 dance companies—plus 40 music and opera ensembles—under AGMA’s umbrella. Fellow creative union Writers Guild of America has proved a useful point of reference. “Freelancers perform in a museum one week, in a theater the next or an outdoor space,” notes Braun. “It’s all over the place, and payment ranges from nothing-at-all to you-name-it. It’s too easy for an employer to say, ‘There are a hundred other dancers I could hire instead,’ and so it quickly becomes an organizing question: How do we create a critical mass in this community?”

Transparency

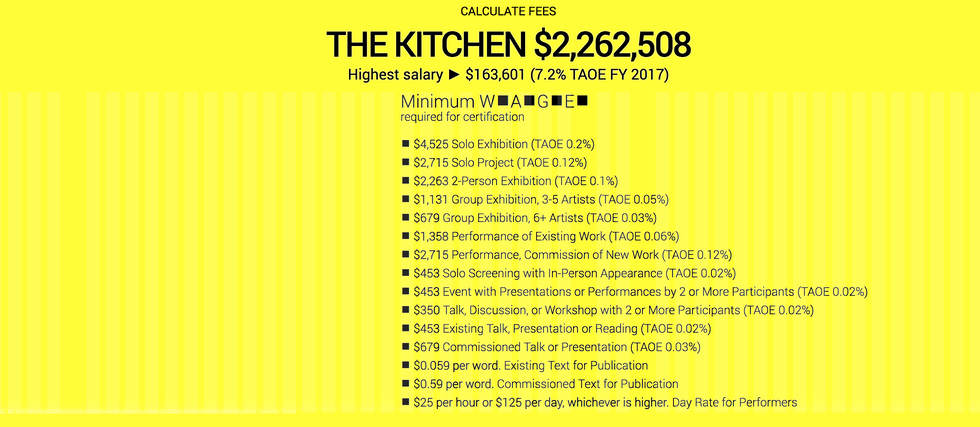

Dance/NYC executive director Alejandra Duque Cifuentes suggests it’s time for dance to develop a tool for financial transparency. One model is what WAGE (Working Artists and the Greater Economy) has done for the visual-arts world, listing baselines for “how much it pays to be in rehearsal, on a panel, in residence or to teach a class,” she says. Danse à la Carte has a similar, nonnegotiable sliding scale used to ensure gender equity when hiring for labs and workshops.

Screenshot via wageforwork.com

Minimum Wage

Despite recent policy wins raising minimum wages in U.S. cities and states, most freelance gigs remain exempt from those regulations. In Montréal, the Regroupement québécois de la danse and the Union des artistes recommend rates based on years of experience. Companies that don’t belong to either group aren’t required to meet those standards, but the fact that they exist applies at least some pressure, says Davies. Freelancer Sophie Breton says dancers earn on average 20 to 30 Canadian dollars per hour.

“Getting paid anything at all is going to be the first step for dancers in a lot of places,” says Bouey. “But the idea that the stresses and mistreatment that older generations went through is a ‘rite of passage,’ as opposed to something we need to dismantle, creates a cycle of financial abuse that doesn’t end.”