A Viewer's Guide to The White Crow, Ralph Fiennes' Rudolf Nureyev Biopic

I caught a preview screening of The White Crow earlier this week at New York City’s 92Y, and I have to say: Even with a solid grasp of dance history and a smattering of film studies knowledge, I had some questions when the credits rolled. The Ralph Fiennes–directed Rudolf Nureyev biopic dramatizes the events leading up to the ballet star’s famous defection from the Soviet Union, touching on incidents from his childhood and his years at the Leningrad Choreographic School.

So before you check out the film (which has a limited release in NYC and Los Angeles today), here are a few details that might be helpful to know.

What’s up with the title?

The meaning of the film’s enigmatic title, The White Crow, is explained straightaway. It’s a Russian term for someone “unusual, extraordinary, not like others, an outsider.” (Aside: Has anyone else noticed Hollywood’s tendency to name ballet-adjacent movies with a color and a type of bird? Black Swan, Red Sparrow, The White Crow…)

The film unfolds across three intertwined timelines.

Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics

The triple-timeline structure utilized by Fiennes and screenwriter David Hare (who is admittedly fond of the device) means that we as a viewer have to work a bit harder to piece together what’s happening. There are three different time periods in play: Nureyev’s childhood, which stretches from his birth on a train in 1938 through his mother dropping him off at his first ballet school; the Leningrad years, 1955–61; and the weeks in Paris leading up to his defection on June 16, 1961.

Even as the film intertwines the three strands, each one unfolds chronologically (with the exception of the bookended opening scene, which features the interrogation of Alexander Pushkin, played by Fiennes, after Nureyev’s defection).

Who was Alexander Pushkin?

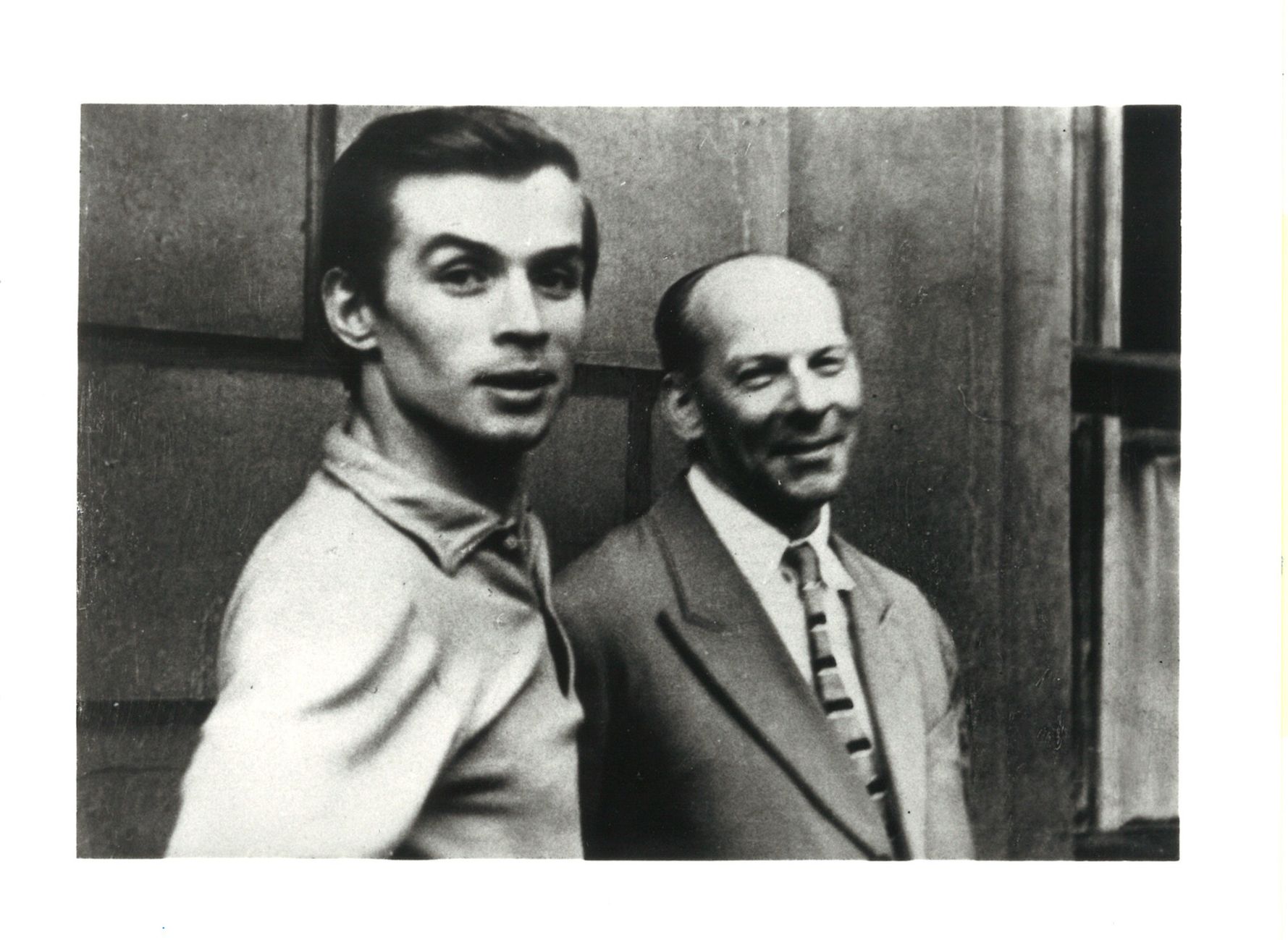

Courtesy DM Archives

Fiennes pulled double duty on the film, not only directing but also playing legendary ballet teacher Alexander Pushkin (not to be confused with the famed Russian writer). As a teacher at the Leningrad Choreographic School (as the Vaganova Ballet Academy was then known), Pushkin shaped the leading male dancers of the Kirov for decades—and Nureyev wasn’t his only famous student. Mikhail Baryshnikov, who, like Nureyev, ultimately defected from the Soviet Union (in 1974), also trained under the master teacher. “This man made me as a dancer,” Baryshnikov once said.

Nureyev (Ivenko) joins the class taught by Alexander Pushkin (Ralph Fiennes) in The White Crow.

Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics

Fiennes’ depiction of Pushkin’s approach aligns with his students’ accounts. It was “a delicate way of teaching,” Fiennes said at the screening, in which Pushkin would suggest ideas or simply ask a dancer to stop and repeat what they’d done to allow them to find and fix their own errors. Baryshnikov described Pushkin as “a very quiet man. A father figure, to us.”

If the dance sequences look great (which mostly, they do), it’s because of a former Royal Ballet star.

Nureyev (Ivenko) performs in The White Crow.

Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics

“I don’t have any interest in ballet,” Fiennes said at the screening, going on to say that he was drawn to the story by Nureyev’s “ferocious sense of destiny” rather than his dancing. “I’m way out of my comfort zone,” he added. Though he watched hours of archival footage of Nureyev’s performances in preparation for filming, the director found himself frustrated by the way all of the footage only used wide angles to show the full body, and was eager to play with camera angles and close-ups during The White Crow‘s dance sequences.

However, Johan Kobborg, who was brought onto the film as both dance consultant and choreographer, convinced him that the scenes needed to be shot to show the dancers’ full bodies, and that the camera should respect the “front” of the choreography. “The dancers are very sensitive to how they’re being filmed,” Fiennes said. “Johan Kobborg said to me, ‘Well, it’s okay, but it looks ugly to me because I’m showing you a specific angle.’ ” They ultimately reshot several of the dance sequences.

Who is the older ballerina who requests Nureyev as her partner?

Natalia Dudinskaya (Anna Urban, née Polikarpova) and Nureyev (Ivenko) rehearse in a still from The White Crow.

Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics

Unless you just so happen to already know this key bit of Nureyev’s Kirov career, it’s unfortunately all too easy to miss this detail. When Nureyev graduated from the Leningrad Choreographic School, he got multiple contract offers but ultimately went to the Kirov, where he made his debut dancing opposite star ballerina Natalia Dudinskaya. She was in her late 40s and within a couple years of her official retirement; Nureyev was a 21-year-old fresh out of the academy.

In The White Crow, Nureyev asks Dudinskaya (portrayed by Anna Urban, née Polikarpova) why she requested to dance with him. “I’ll make you look talented, you’ll make me look young,” is her wry reply. (We couldn’t help but think that this comment was also meant as a nod to Nureyev’s later famed partnership with Dame Margot Fonteyn.)

Yes, the actor playing Nureyev is a real dancer.

As quickly becomes obvious during the film’s dance sequences, the actor playing Nureyev is also an accomplished ballet dancer. His name is Oleg Ivenko, and he’s a leading dancer at the Musa Dzhalil Tatar State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre Company. Much of Nureyev’s technical prowess and pyrotechnics are considered par for the course for today’s male dancers, but we were quite impressed by Ivenko’s attention to detail—he even managed to recreate Nureyev’s distinctive arabesque line. He might not have quite managed the peculiar alchemy that made Nureyev such an explosive performer, (who could?) but he did capture the famed dancer’s “mischievous hauteur” (as Fiennes put it) in his interactions with the other characters.

In fact, there are lots of dancers playing dancers.

In addition to Ivenko and Urban (who enjoyed an extensive career at Hamburg Ballet and now teaches at the company’s affiliated school), the cast also includes Sergei Polunin (before his most recent spate of social media nastiness), Bolshoi soloist Anastasia Meskova and Belgrade National Theater first soloist Margaryta Cheremukhina.

Did Nureyev really have an affair with his teacher’s wife?

Nureyev (Ivenko) sits at a cafe in Paris in The White Crow.

Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics

There are rumors that Nureyev and Xenia, Pushkin’s wife, herself a former dancer, had an affair after the Pushkins invited the young Rudi to live with them. The affair is shown in the film, and while Hare is convinced that they did, it’s impossible to prove or disprove.

It is worth noting that similar rumors dogged Nureyev’s friendship with Fonteyn, and there is some strangeness in the fact that the film is more preoccupied with this alleged affair than it is with its nods to Nureyev’s burgeoning awareness of his homosexuality. The film does seem to assert, however, that the realization of his own sexual orientation may have been one motivation for Nureyev to leave his situation with the Pushkins.

“Are you always this rude?”

Nureyev (Ivenko) and Clara Saint (Adèle Exarchopoulos) in a still from The White Crow.

Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics

Clara Saint (Adèle Exarchopoulos), the French socialite who helped orchestrate Nureyev’s defection, asks him this question in the film. The answer: quite often, yes, as demonstrated in multiple scenes in the film, and worse. Nureyev had a notorious temper—Dame Beryl Grey, who overlapped with him at The Royal Ballet, made headlines two years ago when her memoir detailed instances of the dancer behaving threateningly or violently toward dancers who displeased him. On the flip side, he could be incredibly charming and sweet—like everyone else, Nureyev contained multitudes.

Easter egg: Natalia Makarova’s name appears on a casting sheet.

It’s a there-and-gone moment near the beginning of the film: Nureyev checks the opening night casting sheet in Paris to find his name not listed. But a few lines down? There’s Natalia Makarova. Though she sadly does not appear as a character in the film, we love that the filmmakers included a nod to the ballerina—especially since she defected nearly a decade after Nureyev and landed at American Ballet Theatre.