What Does It Actually Feel Like to Stop Dancing?

Who are you when you no longer do what you’ve been doing for years?

It is the big question facing anyone who retires. For top ballet dancers, however, the situation is more extreme. They start young, grow up in a rarified atmosphere, mostly see only each other, and become more and more removed from ordinary life. So what is it like to give this all up?

I asked seven former principal dancers from different generations at San Francisco Ballet, including myself, about this challenge.

What made you decide to stop performing?

Sally Bailey, danced with San Francisco Ballet 1947–1967:

The idea first came to me on the ’65 tour. I was acting as tour manager as well as still dancing. In one town, the local Community Concerts Board invited us to come to a party after the show. When I made the announcement, one of the younger girls asked, “Is it for dancers, or will people be there, too?”

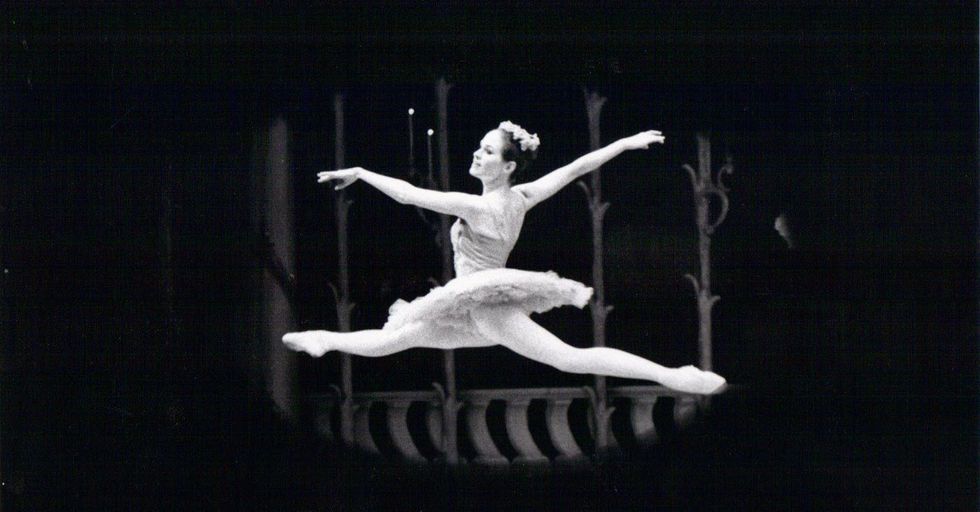

Sally Bailey as Black Swan, 1955, photo by Romaine, S.F.

Dancers

or people?

Her remark made me stop to reflect. Had we dancers removed ourselves so far from ordinary life that we’d become a different species? Touring seemed so normal for us. Get on the bus by 8:00 a.m., jiggle along for four hours to the next town, check in at the motel, adjust to a new theater, perform that night, eat lunch at midnight after having had dinner at noon. Even toe shoes seemed normal.

I said to myself, “Perhaps it’s time for me to get off the bus.”

Around that time, I was appointed assistant ballet mistress and started conducting rehearsals, which I found I did well. The only trouble: I felt myself becoming everyone’s mother, always making everybody do their best, what they knew they should be doing, anyway. I sometimes felt like yelling, “Either do it, or don’t do it. It’s up to you.” I was still dancing some, but I was mostly cleaning up everyone else’s mess. I saw my life becoming narrower and narrower. An image that came to mind was a once-vibrant fall leaf gradually losing its color and drying up. I didn’t want that to be me.

In August I would be 35, the age I had always claimed dancers should stop dancing. I knew, with my body, I could probably dance another five years, but why push it? If I was going to change my life, it would be easier at 35 than 40.

For the first time, I didn’t trust my gut feelings. Were they constructive or destructive? Was I throwing everything away or gracefully letting go?

At first I didn’t talk to anyone about what I was thinking. I didn’t want to tell my family until I’d made up my mind. However, I told my friend Tilly Abbey, who brought me to her family’s doctor friend’s apartment one night. He asked me to tell him what I had on my mind, so I told him. I also mentioned that I wasn’t sure if my thinking was healthy or unhealthy. I remember him saying, “I’m not going to tell you what to do, but I will tell you that your thinking is healthy.”

That was all I needed to know.

What does it feel like today, several years after retiring?

Tina LeBlanc, danced with San Francisco Ballet 1992–2009:

I was standing backstage during Nutcracker last year, and [artistic director] Helgi Tomasson asked, “Do you miss it?” Yes, very much.

Tina LeBlanc in Tchaikovsky Pas de Deux, photo by Erik Tomasson

I still miss parts of being a professional dancer terribly. I miss being that self-involved and focused on my own physicality and artistry, being lost in self exploration. I miss how my body felt when it was in peak condition and responding to the commands I gave it. I miss that time before a show when I was readying myself for a show, make-up, warm up, costumes…the ritual. I miss leaving the theater at night when it’s empty (I would always walk across the stage and stare out at the empty house). I miss the rush I would get when I would step on stage and feel the exchange of energy with the audience. I miss the feeling of contentment after a good show (which didn’t always match the audience’s response). And of course, I miss being known. I’m rarely recognized anymore. The fame of a ballet dancer doesn’t last much longer than the actual career because there are always dancers coming up who are wonderful and talented. On to the next!

If I could have continued feeling like I was in peak form, I would have, but bodies age. I wanted to retire. I was excited to get to the next phase, but that 27 years as a professional dancer will always be the best part, I think. It is a way of life that not many people get to experience.

What was the first thing you did right after you stopped dancing?

Gina Ness, danced with San Francisco Ballet 1972–1985:

I cut my hair! I went to a salon close to Union Square and had it cut very short. I felt this was the symbolic first step of my not being a performing ballet dancer anymore. As I watched my long, thick hair get shorter and shorter, I remember thinking that I was looking more and more like my brother Tony!

Gina Ness as The Rose in Nutcracker

After my final performance I continued to take my daily class. I loved the classes of Yehuda Maor at Dancers Stage. Taking that class had been part of my life since I was very young. I just couldn’t drop ballet like a hot potato! I was in great shape when I retired. Then, after about six months, it finally dawned on me that I didn’t need to do this anymore.

What was your last performance like?

Anita Paciotti, danced with San Francisco Ballet 1968–1986:

It was as Medea in Michael Smuin’s ballet of the same name. It was fraught with drama over who should give me my final flowers: Helgi Tomasson (our new director) or Michael (our former director). Helgi did not approve of Michael on the stage. With all sorts of trickery behind the scenes, and unbeknownst to me, Michael wrapped himself up in the downstage curtain and wound up on stage with his bouquet together with Helgi. It was quite a scene.

Anita Paciotti in Giselle, photo by Erik Tomasson

But my favorite memory is something quite different. In a concluding scene, I discovered a “new way” of playing the scene. I didn’t plan or expect it. I just felt it. It felt completely right, and how funny, yet how perfect, on that last night. We are always learning!

How did you choose what to do next?

Anton Ness, danced with San Francisco Ballet 1972–1980:

The months that followed my retirement were a time of my body healing, yet experiencing new kinds of stress. I had joined the Monday-Friday/8-5 schedule at my father-in-law’s printing paper company, beginning in the warehouse. I was filling orders, loading and unloading trucks, driving a forklift. I reveled in nights and weekends free, yet felt a bit lost being low man on the totem pole in the regular workforce. I wondered of my future value and contribution to anything of lasting importance. I was an artist in a strange environment that couldn’t allow for that creative expression. Take the order, fill the order, deliver the order. That was now my world.

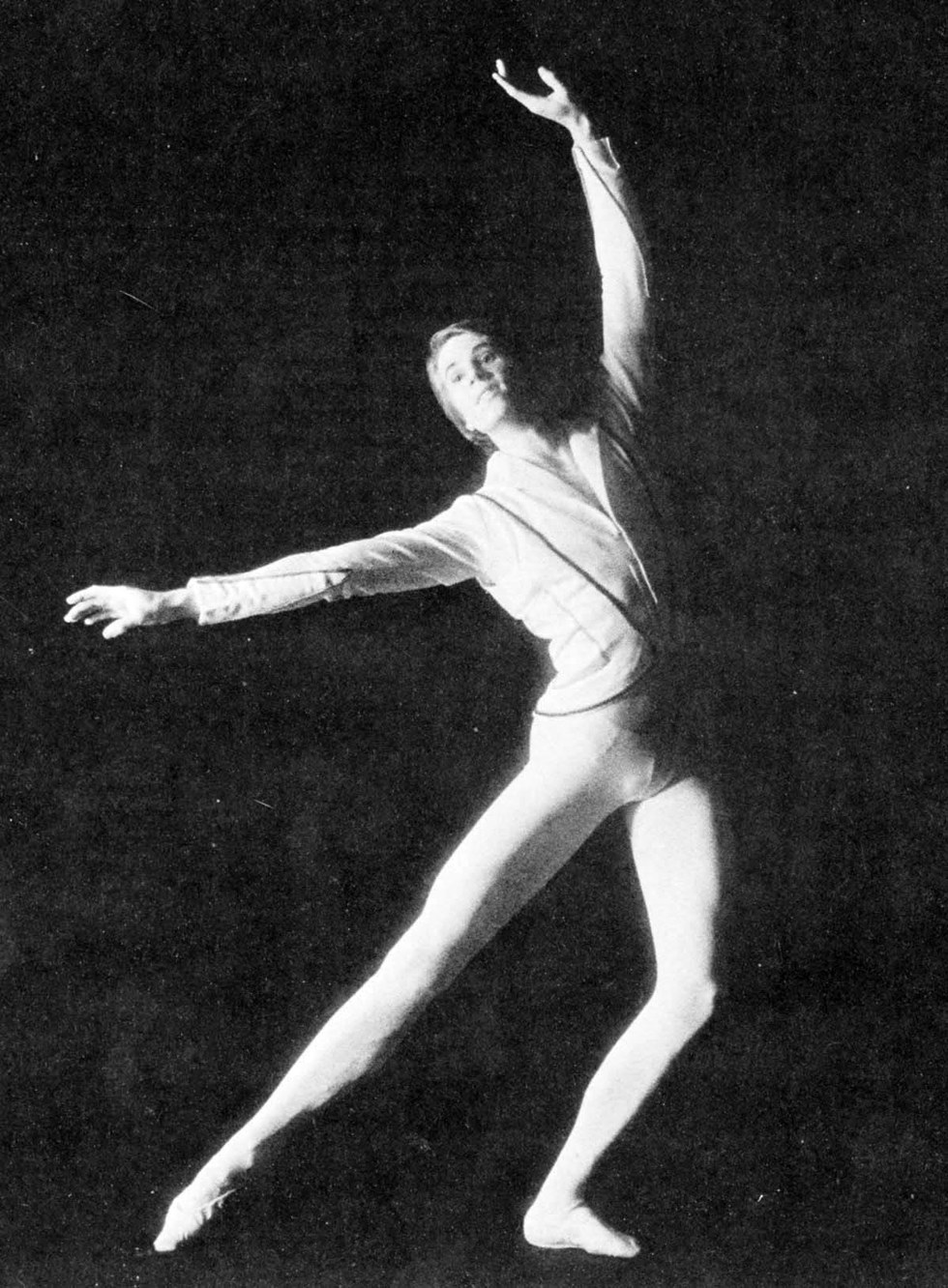

Tony Nessin Michael Smuin’s Pulcinella Variations, photo by Robert Simac

Then the nightmares began. They haunted me on and off for more than a decade. They always begin with my landing, and while going to the theater, suddenly being pressed to perform whilst I explain I’m out of shape, don’t remember the choreography, and so on. I’m totally panicked and wake in a cold sweat.

Ten years later, having moved to Seattle—working into the position of territory manager for Unisource Paper—Vivian Little, a former SFB soloist teaching nearby asked if I would participate in her recital. She wanted me to partner her in Paquita. I agreed only if we could dance something less classical in addition. We agreed, and I set a pas de deux to John Barry’s score for the movie “Somewhere in Time” combined with Rachmaninoff’s “Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini.” This performance was my reconnection with dance, a creative step forward, and a chance, though she was young, for my oldest daughter to see me dance one time.

I slowly returned to my artistic side while still working. I set a Nutcracker for my kids’ school and found my way to being a director of a large fine art photography gallery. And after again retiring, I authored a book “Save Our Ballet,” about the period during 1974 when SFB was facing bankruptcy. Then I embarked on my own photography, with handcrafted frames and archival mounting of my prints.

After more than three decades, I classify myself as an artist once again, proving the point that we can change our skins as necessary to provide for our family, but also be true to our inner self.

When did you first ask the question, “Who am I if I’m not a dancer?”

Katita Waldo, danced with San Francisco Ballet 1988–2010:

That’s not a question I have ever asked myself. I have always had a life outside of dance. My husband Marshall Crutcher and I were married in 1989 and we have a son James, who was born in 1999. Marshall founded a media film business and ran it for about 25 years, but is now moving back into classical music and composition.

Katita Waldo in William Forsythe’s The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude, photo by Eric Tomasson

We have lots of friends, most of whom don’t dance, so most of our social time is spent without ballet even being mentioned. I like to cook, read, and our family is big on movies (Netflix is HUGE in our house!). Ballet was, and is, what I do for a living, but remains just a part of the picture. I am lucky that I have had a career that I enjoy, but it is only one part of me, so I am exactly the same person as when I danced.

Do you still consider yourself a dancer?

Pierre Vilanoba, danced with San Francisco Ballet 1998–2013:

About six years before my retirement, I went back to school to get a bachelor’s degree in performing arts, with an emphasis on psychology. During an interview with a psychoanalyst friend for a book I was writing, he shared a story with me about a 70-year-old woman who had been a dancer and was still feeling that she was a dancer. It took me some time to understand what he was trying to make me see.

Pierre Vilanoba in William Forsythe’s In the middle, somewhat elevated, photo by Erik Tomasson

The fact is that after spending over 30 years perfecting ballet, the mental set does not go away. It is part of who we are. We behave the way we do because we are dancers. Our minds are working the way they are because we have had this experience. Our perspective is the one of a dancer, or retired dancer, but there is still the dancer part in it.

Today I embrace this part of who I am, and I am trying to develop other parts of who I am, but they will necessarily be influenced by the dancer inside of me.