These Are Our “25 to Watch” Picks for 2019

What’s next for the dance world? Our annual list of the dancers, choreographers and companies that are on the verge of skyrocketing has a pretty excellent track record of answering that question.

Here they are: the 25 up-and-coming artists we believe represent the future of our field.

Evan Ruggiero

Evan Ruggiero’s story started as something out of A Chorus Line—aged 5, he said, “I can do that” after seeing his sister’s dance class. He got so good he performed with the New Jersey Tap Ensemble, and was obviously headed to Broadway after college. But when he was diagnosed with bone cancer at 19, the story veered off its well-worn track and became something else altogether—inspirational amputee tap dancer on YouTube graduates to a dance career as the latter-day incarnation of the legendary Clayton “Peg Leg” Bates.

Nearly a decade after his diagnosis, Ruggiero is rewriting the story yet again. Not content to remain a novelty act, he danced, leapt, fenced and fought his way through the rollicking off-off Broadway musical Bastard Jones, a boisterous adaptation of the 18th-century novel The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling. As the lusty, big-hearted title character, he was alternately charming, funny, soulful—and he can sing, too. The production did nothing to disguise his prosthetic leg—it became a comic prop or a handy weapon as necessary, and melted away the rest of the time, just part of his mesmerizing dance toolbox. —Sylviane Gold

Siphesihle November

With his debut as Bluebird in Rudolf Nureyev’s production of The Sleeping Beauty last spring, National Ballet of Canada corps member Siphesihle November quickly established himself as the rightful heir to one of the most challenging male parts in the classical repertoire. While standing only 5′ 7″, November dances tall. His buoyant jump and clean lines were honed at Canada’s National Ballet School, but he possesses a charisma that comes from his early years dancing to kwaito, an energetic style of house music popular in his hometown of Zolani, South Africa.

His debut in the virtuoso role came less than nine months after his graduation from NBS. The now-20-year-old has already further tested his innate talents this season on Puck, the impish fairy driving the plot in Sir Frederick Ashton’s The Dream. “I think it’s any dancer’s ambition to get out of the corps and take on more solo roles,” November says. “I am looking forward to the next chapter.” —Deirdre Kelly

Giselle. Photo by Jennifer Zmuda, Courtesy BalletMet

Sophie Miklosovic

A mix of youthful innocence and vulnerability characterized Sophie Miklosovic’s Juliet this past August. Dancing Romeo and Juliet‘s balcony scene pas de deux, she attained a level of artistry that equaled her expert technique. Delicate port de bras accompanied textbook footwork as Miklosovic embodied Juliet’s elation and trepidation.

The former competition dancer from Detroit says she always had an affinity for tiaras, but that competing was more than that: It was instrumental in honing her natural skills as a dancer. She earned top honors at the 2015 and 2016 Youth America Grand Prix and a gold medal at the 2017 World Ballet Competition. BalletMet artistic director Edwaard Liang hired her in 2017 when she was only 17.

Despite her many early successes, Miklosovic says the constant challenge of ballet keeps her grounded: “Working to achieve something difficult in a split second is what keeps me going.” —Steve Sucato

PowerShift. Photo by David Gonsier, Courtesy Taylor

Micaela Taylor

With a natural facility that speaks contemporary and hip-hop languages fluently, Micaela Taylor got her professional start dancing for renowned Los Angeles companies like BODYTRAFFIC and Ate9. But since founding The TL Collective in 2016, she has chosen to perform exclusively in her own unique vocabulary, a fusion of styles she dubs “contemporary/pop.” Informed by her training in both Vaganova and commercial dance, it’s a quirky mix of funky moves layered over a more formal, grounded modern technique, full of jutting elbows and juicy knees.

The daughter of a pastor, Taylor has a big vision and is not afraid to reflect on difficult themes ranging from information overload to community crisis. A subtle spirituality emanates from her dances through an intuitive musicality that utilizes syncopation and counterpoint. Yet, even in fast, complex phrases of movement and gesture, Taylor and The TL Collective surprise in their ability to come together in virtuosic unison.

With upcoming premieres for both BODYTRAFFIC and Gibney Dance Company, as well as an Inside/Out appearance at Jacob’s Pillow and a full-evening premiere at L.A.’s Ford Amphitheatre for her own company later this year, Taylor’s theatrical street style is fast finding support and enthusiastic audiences on both coasts. —Candice Thompson

Romeo and Juliet. Photo by Rosalie O’Connor, Courtesy ABT

Aran Bell

Performing Romeo as a 19-year-old corps member would be a feat at any company. But at American Ballet Theatre, where it can take dancers near decades to land promotions and principal roles, it’s nothing short of a coup. Yet when Aran Bell did just that last summer—in New York City, at the Metropolitan Opera House, no less—he did it with a gravitas it takes most dancers years to develop and a sincerity only an actual teenager could bring to the role.

Bell was hardly an unknown before his debut. He was profiled in the 2011 documentary First Position, where at age 11 he was already raking in awards and turning like a top. But he hasn’t rested on his prodigy laurels. Though he’s still a virtuoso technician, he’s also a refined actor with an unflagging work ethic—he even spent an extra year in the ABT Studio Company in the midst of a challenging growth spurt. Now 6′ 3″, he’s a natural partner, dancing with some of ABT’s starriest women, such as Misty Copeland and Stella Abrera. But his Romeo debut was perhaps his greatest triumph thus far, tackling Sir Kenneth MacMillan’s near-impossible lifts with ease and finesse. —Lauren Wingenroth

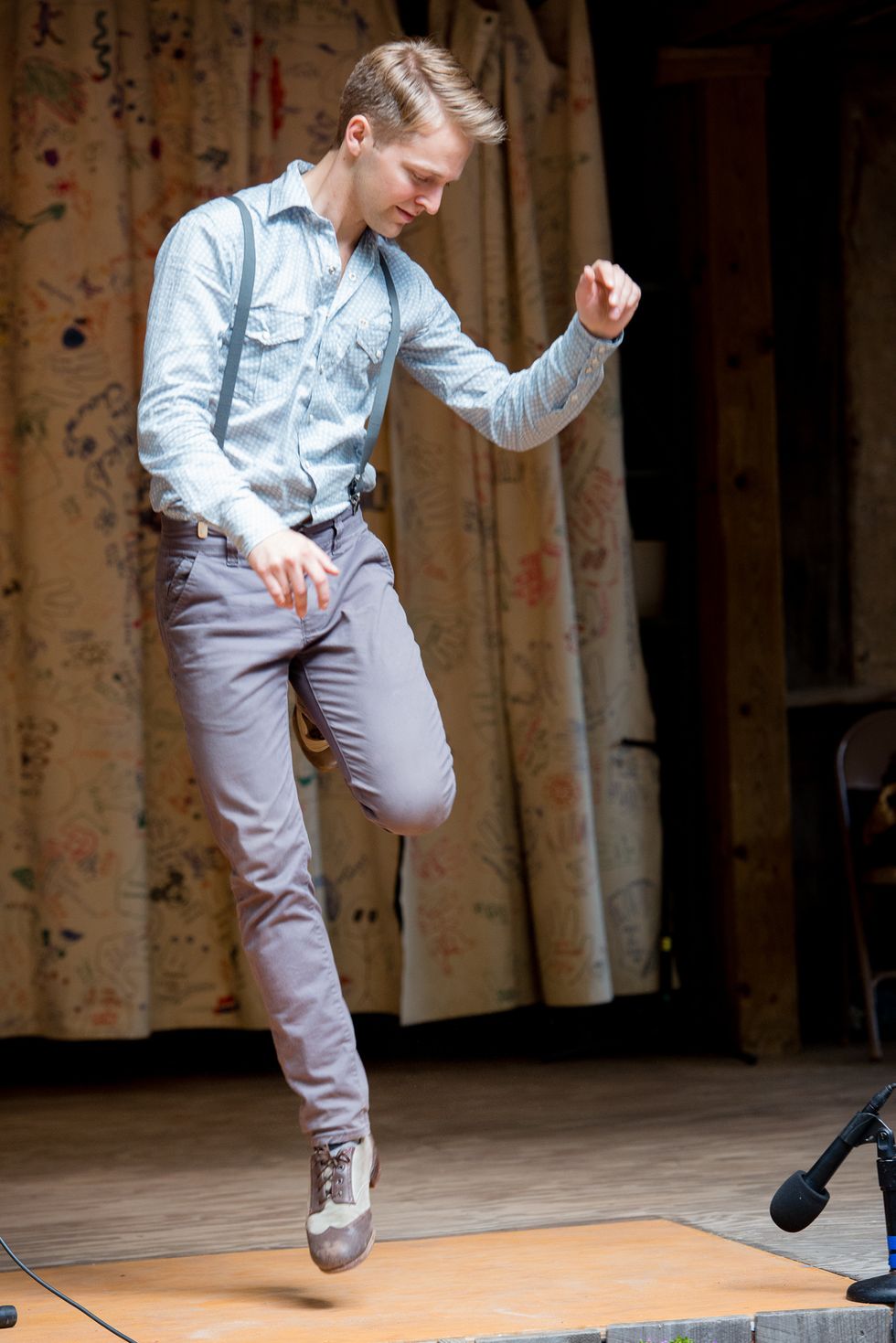

Nic Gareiss

Mild-mannered radical Nic Gareiss is not just one to watch, but one to hear. He brushes, scrapes, scratches and strokes the floor from a repertoire of moves and sounds drawn from various traditional step-dance forms—Appalachian clogging and Irish and Canadian step dance, to name a few. He susurrates, whispers and sibilates with his feet in gently subversive ways—mindful of the forms’ conventions and then questioning and playing with them so that they speak to us as aptly today as one hundred, two hundred, three hundred years ago.

The Michigan-born dancer charms you the moment he enters his intimate performance spaces—a gentle, sweet smile lighting his face, eyes lowered. “When I walk into a room,” he says, “there’s a sense of beginning with quietness, of dynamic build. Everything feels like it’s about pleasure and how can we share pleasure together in this moment, between performer and audience.”

For the past six years, Gareiss has spent an average of 36 weeks a year on the road, wherever new projects and fellow sound-making collaborators beckon. In 2019 he is taking the art and tradition of step dancing to people one home at a time with his show Solo Square Dance. How big is your living room? All he needs is an 8′ by 8′ space and your attention. —Emma Sandall

Serenade. Photo by Peter Mueller, Courtesy Cincinnati Ballet

Chisako Oga

Whether executing snappy, precision pointe work as Coppélia or graceful turns and leaps as the Russian Girl in Balanchine’s Serenade, Chisako Oga arrests attention. The 22-year-old technical wunderkind showcased all those qualities, plus riveting acting abilities, during her first season with Cincinnati Ballet as Guinevere in artistic director Victoria Morgan’s King Arthur’s Camelot. Oga’s passionate dancing melted hearts and sent pulses racing with daring runs and leaps into her partner’s arms.

Born in Dallas, Oga swiftly rose from trainee at the San Francisco Ballet School in 2015 to Cincinnati Ballet principal dancer in 2017. Her talents won her a silver medal at the 2016 Shanghai International Ballet Competition and a bronze at the 2018 USA International Ballet Competition. Says Oga, “I want to be the kind of dancer that touches hearts and inspires people.” —Steve Sucato

Apollo. Photo by Natasha Razina, Courtesy State Academic Mariinsky Theatre

Maria Khoreva

Her frequent dance videos and musings in English have earned 18-year-old Maria Khoreva more Instagram followers than superstars Diana Vishneva and Maria Kochetkova. While it’s hardly a guarantee of stage success, she isn’t just a social media phenomenon. Her airy precision and lively stage personality won over the Mariinsky Ballet, too: Within a month of her graduation from the Vaganova Ballet Academy last summer, she had joined the company and was dancing Terpsichore in Balanchine’s Apollo, as well as a pas de deux from Sir Frederick Ashton’s Marguerite and Armand, alongside principal Xander Parish.

Khoreva has been documenting her transition into company life through sweet, cheerful Instagram posts about everything from muscle fatigue to St. Petersburg weather. Thanks to her popularity, she is a Nike ambassador and Bloch has made her a spokesperson. This savvy Russian ballerina already has a global audience at her fingertips. —Laura Cappelle

Allegro Brillante. Photo by Erin Baiano, Courtesy NYCB

Roman Mejia

New York City Ballet has a long tradition of testing young corps members with leading roles. But no one has had quite as fast a rise lately as 19-year-old Roman Mejia—and he seems perfectly ready for more. Last February, just three months after joining the corps, he was handed the meaty role of Mercutio in Peter Martins’ Romeo + Juliet. Wearing a sly, side-cocked smile, he danced with a perfect mixture of musicality, thrilling bravura and unflappable self-confidence. In the same season, he danced soloist roles in Jerome Robbins’ Fancy Free and The Four Seasons, his performances as instinctive as if to the manner born.

In a way, he was. Mejia is the son of former NYCB dancer Paul Mejia and Fort Worth Dallas Ballet principal Maria Terezia Balogh. He trained at his parents’ school in Texas before following in his father’s footsteps at School of American Ballet and NYCB. Compact and boyish, Mejia is a shoo-in for NYCB’s Edward Villella roles (he’s already tackled Tarantella at the Vail Dance Festival). And with the recent retirement of principal Joaquin De Luz adding to the current dearth of leading men, we’re likely to see a lot more of him. —Amy Brandt

Your Flesh Shall Be a Great Poem. Photo by Erik Tomasson, Courtesy SFB

Benjamin Freemantle

When Fred Astaire danced with a hat rack, and Gene Kelly with an umbrella, their exuberance infused life into those inanimate objects. Benjamin Freemantle did the same with a wooden footstool in the world premiere of Trey McIntyre’s Your Flesh Shall Be a Great Poem, during San Francisco Ballet’s Unbound festival. In a feat of choreographic galvanism, Freemantle made us believe the stool was his partner, tenderly cradling it, balancing it and rolling over it with more than enough lyricism for them both.

Freemantle, just 22 at the time and recently named a soloist, came into his own during Unbound, also dancing featured roles created on him by Christopher Wheeldon and Dwight Rhoden. But it wasn’t the Vancouver native’s debut in the spotlight. In his first year in the corps, he danced Lensky in Onegin opposite Dores André’s Olga. Since, he’s also created a part in Benjamin Millepied’s The Chairman Dances—Quartet for Two and snagged soloist spots in Wheeldon’s Cinderella and Helgi Tomasson’s Swan Lake. Those roles barely tapped Freemantle’s talent, his star turn in Unbound showing that there are even greater things to come. —Claudia Bauer

Gimp Gait. Photo by Mitchell Zachs, Courtesy Winter

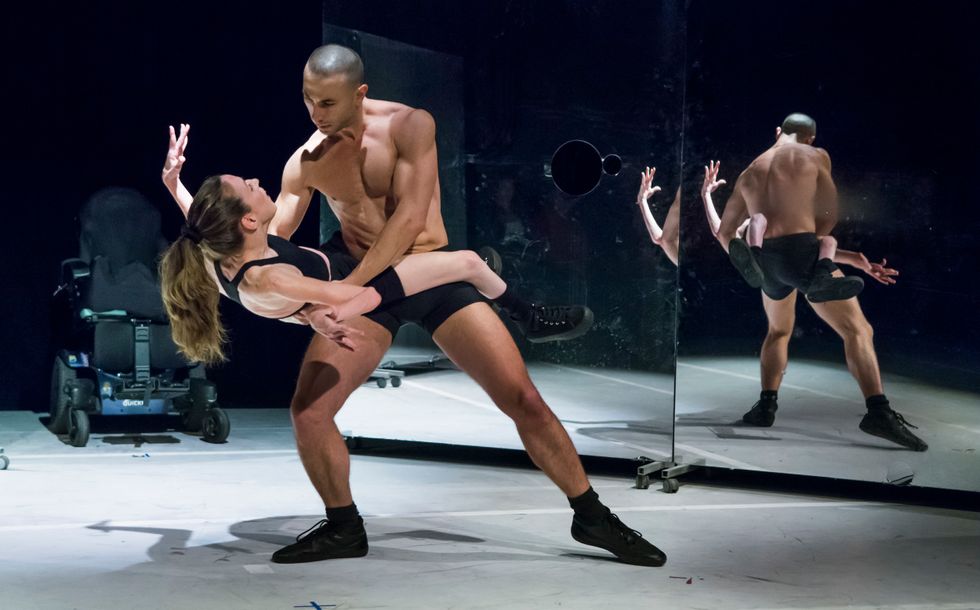

Pioneer Winter Collective

Pioneer Winter Collective

confronts issues all too often ignored. With technical rigor and unflinching rapport, director Pioneer Winter and his collaborators skillfully tackle topics concerning people of varied physical ability, body type, gender identity and sexual orientation. For example, in Reprise, a gay man of color commands, from his wheelchair, unison poses or the foot rhythms of a flamenco dancer. As compliance erupts into rebellion and control swerves into cooperation, moves traverse spheres of power and turn trespass into authority.

PWC also ventures beyond theaters: Through LEAP (Leaders of Equality through Arts and Performance), a framework the company uses to engage the community in social justice dialogue, it held creative leadership summits for LGBTQ youth and allies in 2017 and 2018. Its biennial Grass Stains fosters site-specific works by choreographers and performance-based artists with alternative outlooks. Ahead lie more pieces about intersectionality, including a commission featuring a young basketball wiz, as well as more site-specific work and films. Every project champions the striving for personal authenticity, for in life as in art, Winter insists, “being truly human can be the hardest part.” —Guillermo Perez

Two and Only. Photo by Altin Kaftira, Courtesy Dutch National Ballet

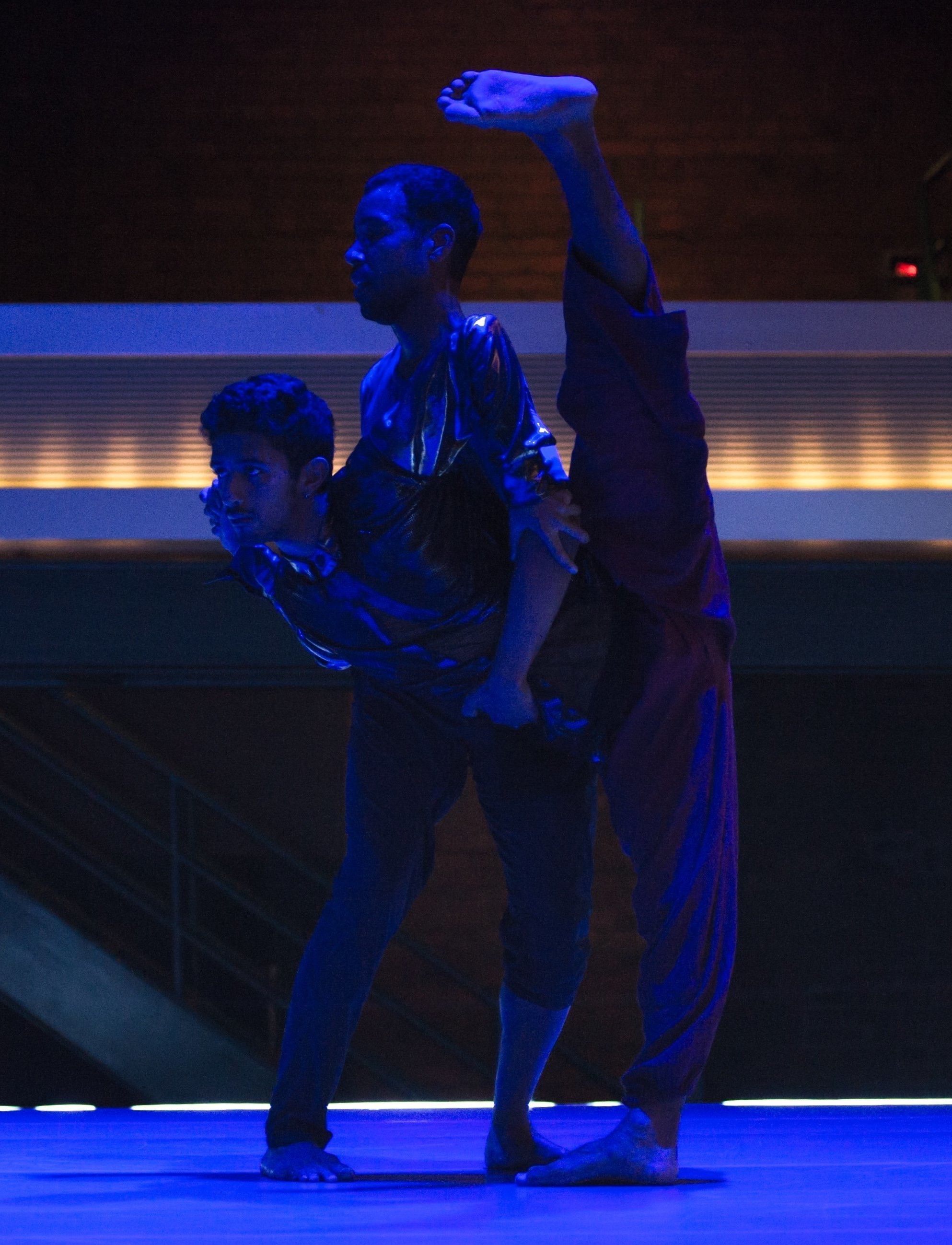

Wubkje Kuindersma

It didn’t take long for Wubkje Kuindersma to establish herself as a choreographer on Dutch National Ballet’s stage. In just 10 minutes, her Two and Only portrayed rare emotional intimacy between two men—veteran principal Marijn Rademaker and an apprentice, Timothy van Poucke. The duet she crafted was full of fluid, musical partnering, capturing the emotion in two folk songs performed live by singer-songwriter Michael Benjamin without ever looking sappy. It stood out even alongside a work by Hans van Manen, the Dutch neoclassical master, earning Rademaker a Benois de la Danse nomination.

Born in Cameroon, Kuindersma trained in Rotterdam and danced with companies including Danish Dance Theatre and Wayne McGregor’s Random Dance. Since 2009, she has steadily built up her resumé as a freelance choreographer. 2018 turned into a breakthrough year: Following Two and Only, she served as an Artistic Partnership Initiative Fellow at New York University’s Center for Ballet and the Arts. In November, she also premiered a new work for Philadelphia’s BalletX. Add Kuindersma to the list of female choreographers ready for bigger stages. —Laura Cappelle

Adeene Denton

If a graduate student, when asked about their intended career, states they’re going to be an astronaut, it’s best to take them at their word. Since coming to Brown University in 2016 to earn her Ph.D. in planetary geology, Adeene Denton has used her dance practice to consider how bodies might move and generate meaning during interstellar travel. Her research question, as articulated in her hilarious TEDx talk, “Netflix and Chill at 0 Kelvin,” is, roughly, How will we dance when unconstrained by gravity?

This is no idle speculation. For NASA to engage in long-duration space flight, creative culture must be considered alongside more obviously scientific concerns. (Getting to Mars takes a super-long time. Art and expressiveness help prevent astronauts from getting bored.) Denton, meanwhile, has a terrestrial repertory—charged, intricate dances that have been shown around New England—and her recent research makes her arguably the best-suited individual on the planet to choreograph in microgravity. This is the mark of a specific brand of dance innovator: the scientist-artist who, by dint of their research, composes the outer limits of a field that doesn’t quite exist. Yet. —Sydney Skybetter

Tanya Chianese

With visceral, sometimes uncomfortably intimate dance, choreographer Tanya Chianese took on sexual harassment in her 2018 work Nevertheless. Accompanied by the a cappella group Cat Call Choir, Nevertheless packed an emotional wallop. Buzz about it even reached Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren (who inspired the feminist catchphrase “Nevertheless, she persisted”); Warren’s assistant called to congratulate the Oakland-based choreographer on her work.

Whether her topic is hard-hitting or abstract, Chianese, 30, draws you along a story arc with a sense of theatrical composition that’s rare among choreographers more than twice her age. That quality has been apparent since the evening-length debut of her company, ka∙nei∙see collective, in 2015’s Cookie Cutter. She risked twee obviousness by using actual cookie cutters as props, but the result was a wry referendum on conformity. In 2016’s Duchamp-inspired Readymade, dancers unfurled dozens of toilet paper rolls during a kaleidoscope of solos, duets and ensembles. “My company name is a play on the words ‘can I see,’ ” Chianese says. “What are you seeing? It’s finding the things that change our perspective.” —Claudia Bauer

Jessica He

Harmonies emanate from Jessica He as she springs into arabesques in Balanchine’s Tschaikovsky Pas de Deux, her port de bras generous, her feet as sensitive as a pianist’s hands. In Craig Davidson’s Remembrance/Hereafter, she plunges into spiraling falls and inverted lifts with urgency and a disarming sense of trust in her partners. In Balanchine’s Who Cares? she lingers for a split second at the top of each high développé, her hips and shoulders coyly catching Gershwin’s pulse.

Remembrance/Hereafter. Photo by Gene Schiavone, Courtesy Atlanta Ballet.

The California-born graduate of The Rock School for Dance Education, newly recruited into Atlanta Ballet from Houston Ballet II last season, breathes freshness into any work she dances. She showed grace under pressure when she stepped into the lead role in Davidson’s ballet just three days before the premiere last March. The role drew attention to He’s innate ability to dance inside the notes as if in tune with a composer’s inspiration. This musicality, proportionately blended with technical strength and a palpable sense of joy, makes He an embodiment of classicism—and an emerging muse. —Cynthia Bond Perry

Joshua Culbreath

Joshua Culbreath gets to and from the floor like lightning. A 28-year-old veteran of the cypher and the stage, he combines speed with a determined improvisational style that draws you to the edge of your seat. Fierce and fast in the circle, a space that he says “is for talking to my closest friends,” he insists it doesn’t get more personal than a battle. By comparison, “It’s a little like dreaming once that spotlight hits the stage. The audience fades.”

Culbreath, aka BBoy Supa Josh, has performed for a decade with Rennie Harris Puremovement, where he also serves as rehearsal director and leads RHAW, its training company. Rarely idle, he dances often with Raphael Xavier and reps his own crew, Retro Flow. Fresh off the Red Bull BC One circuit, you can catch Culbreath playing in the pocket in his solos, where he aspires to be “an extra instrument” and dance with the music rather than to it. —Anna Drozdowski

Jasmine Harper

There’s a deep soulfulness to Jasmine Harper’s movement. Her dancing is precise, yet fluid, featuring an intricate musicality that’s rare on today’s commercial scene. In the five years since her stint on “So You Think You Can Dance,” the 25-year-old has rocketed into Los Angeles’ current commercial dance zeitgeist.

After performing with Beyoncé during her Super Bowl 50 performance in 2016, Harper appeared in the star’s video for “Formation.” Most recently, she danced with Queen Bey at Coachella (dubbed “Beychella” after the performance went viral), appeared in the iconic music video for “APES**T” that was filmed at the Louvre Museum, and performed in Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s On the Run II tour last year.

“I try to let the music speak through my movement,” she says. “I want the audience to feel what I feel when I’m performing.” —Courtney Bowers

Swan Lake. Photo by Arian Molina Soca, Courtesy Pennsylvania Ballet

Sydney Dolan

Seventeen-year-old Sydney Dolan’s career at Pennsylvania Ballet has been nothing short of meteoric. Last year, as an apprentice, the 2018 Princess Grace Award recipient performed Lilac Fairy in The Sleeping Beauty, Dewdrop in Balanchine’s The Nutcracker, the pas de trois in Angel Corella’s Swan Lake and Tall Girl in Balanchine’s “Rubies.”

“She’s exceeded expectations with everything we’ve given her,” says Corella, Pennsylvania Ballet’s artistic director. “She’s the perfect example of what an artistic director is looking for in a dancer: someone who works hard to get their reward. She’s a wonder.”

Now a member of the corps de ballet, Dolan’s technique is equal parts clean, correct and dynamic, yet she brings an abandon to each role that’s raw and knowing. “She’s done so much in such a short time,” Corella adds. “She’s already a star now. Imagine what will happen when she becomes a principal.” —Haley Hilton

The Rare Birds: Cristina. Photo by François Martinez, Courtesy Hall

Cristina Hall

Cristina Hall crafts the lines of her body like an architect, no detail slipping her awareness. In traditional flamenco settings, she commands the space with her precise footwork and explosive energy. Her choreographies weave together unique body percussion with never-before-seen footwork combinations, using nontraditional production elements and addressing decidedly contemporary concerns. When she choreographed to Nina Simone’s “Blackbird,” impeccable technique allowed her to seamlessly merge flamenco’s intense musicality with graceful strokes of her upper body. (The work was a finalist in the Sadler’s Wells Global Dance Contest in 2011.) In 2017, she imaginatively combined flamenco and electronic music to explore what it means to be human in the digital age with Bionic, which won Madrid’s Tetuán District Choreographic Contest.

As an American flamenco artist in Spain, Hall has relentlessly fought to prove herself. Perhaps that struggle fuels her palpable emotion onstage: Her willingness to be vulnerable lends an honesty and realness to her presence. With her dazzling originality, Hall is breaking boundaries in flamenco and beyond. —Alice Blumenfeld

Gully spring: Di exhortation. Photo by Scott Shaw, Courtesy Watt

Shamar Wayne Watt

Jamaican-born dancer Shamar Wayne Watt demands the audience’s full attention; his focus slices through the room like a laser. In his Gully spring: Di exhortation, a plastic gallon jug of water slowly drips over his head as he circles the microphone hanging just above mouth level. Watt’s spoken text interrogates white supremacy and colonialism; his delivery is akin to a revolutionary preacher. Both movement and voice demonstrate a deft sense of tension and flow.

The Bessie-nominated artist has worked with nora chipaumire since he was a student at Florida State University. “I immediately gravitated toward the unapologetically intelligent, nonconforming and hyper-swaggering blackness she exudes,” Watt says—a description that could fit him, as well. Now, as his career moves forward, Watt is interested in developing what he describes as an insurgent aesthetic, revaluing bodies, perceptions and stories that have been deemed without value. —Nicole Loeffler-Gladstone

SWITCH. Photo by Paula Lobo, Courtesy Morland

Paul Morland

When Paul Morland dances, the very air molecules around him seem to vibrate. Whether he’s immersed in MADBOOTS DANCE’s aggressive, hyperphysical vocabulary or Gallim’s syrupy, humanistic rituals, he tackles movement with a ferocious attack and an inexplicable elasticity. His calm, considered manner makes the flurry of motion spinning out from his zen center seem perfectly natural. Some dancers seem to bend time; he bends space, as well.

The former competition kid (and New York City Dance Alliance Foundation Dance Magazine College Scholarship winner) has all of the tricks you might expect, plus the smooth contemporary technique that’s a signature of his alma mater, New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. Both have been put to good use: Since graduating in 2017, Morland has performed in Andrea Miller’s Stone Skipping at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, appeared at The Joyce Theater with both MADBOOTS and Rashaun Mitchell + Silas Riener, and traveled from La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club in New York City to Italy’s Spoleto Festival with Stefanie Batten Bland. These days, you can find him touring the U.S. with the Hofesh Shechter–choreographed Fiddler on the Roof, dancing in the ensemble and portraying the titular fiddler. —Courtney Escoyne

Easton Payne

When it first hit the competition stage, Easton Payne’s work—set to bold song choices like classic Frank Sinatra, and devoid of standard tilts and pirouettes—was a breath of fresh air. The 21-year-old choreographer started making waves on Instagram in 2015, posting one markedly different combo after another while cultivating something of a cult following in the process. Payne’s unapologetic singularity quickly caught the eyes of dancers, teachers and commercial-world standouts alike. Soon, he was choreographing routines for some of the country’s top competition kids, while getting cast in everything from concept videos with Tyce Diorio to fashion collaborations with Adidas.

Like any young professional, he has his fair share of career bucket list items (namely, choreographing a Broadway show). But for now, he’s as content as can be, returning to Los Angeles when he isn’t choreographing for studios across the country. “I will never truly fit the mold,” he says, “but that’s the common human experience—discovering how to ‘fit’ without sacrificing our innate shape.” —Olivia Manno

Everything you have is yours? Photo by Karl Cooney, Courtesy Ahuvia

Hadar Ahuvia

Hadar Ahuvia

‘s Everything you have is yours? teeters on the edge of disaster. She has a clear agenda, and sometimes stops for lecture-demonstration style moments that could easily turn didactic. But they somehow never do. Content that, in the hands of another choreographer, could feel like it’s being shoved down an audience’s throat is instead thoughtfully doled out with nuance and humor. Ahuvia takes risk after risk, and watches them each pay off in a powerful piece of dance theater—earning her a 2018 Bessie nomination for Outstanding Breakout Choreographer.

Looking at Ahuvia’s performance resumé, her savvy, sophisticated style comes as no surprise: She’s worked with downtown favorites like Sara Rudner, Anna Sperber and Jon Kinzel, and is a regular, compelling presence in the work of Reggie Wilson. But for the 33-year-old Israeli-American choreographer, a significant part of her practice happens offstage, through workshops where she teaches “deconstructed” versions of Israeli folk dances and imparts the context and complications she feels are all too often missing. —Lauren Wingenroth

Carriage. Photo by David Kasnic, Courtesy Davis

Matty Davis

“I grew up just crushing my body against asphalt,” says Matty Davis, who pursued aggressive rollerblading and snowboarding alongside baseball, soccer, hockey, and track and field. “I’d jump 24 stairs on a pair of skates and smash my crotch on a railing. I separated my shoulder and dislocated all the fingers on my left hand.” After a table saw went through four of the fingers on his other hand, he had “a minor amputation, several bone fusions and a bone graft.”

Combine that kind of pain threshold and appetite for risk with Davis’ studious nature—he has a research-heavy creative process and two art degrees—and you get unforgettable choreography. Carriage, a series of intensely physical, site-specific duets with Ben Gould, occurred in a wide variety of locations, including the deck of a boat cruising between Chicago’s riverside skyscrapers. Wood bone mill‘s escapades were set in and under a stately mulberry tree and repeated during each of the four seasons; in winter, three ground fires burned while Davis and Bryan Saner climbed, sparred and leapt from high branches.

Davis, just shy of 30 and based in New York City, remains cagey about dance. “I auditioned for a lot of companies back in the day and I’m grateful some of that stuff didn’t work out,” he says, laughing. In 2012, he co-founded BOOMERANG with Adrian Galvin and Kora Radella; they sunset the group as Davis prioritized other projects. This year, he’ll continue collaborating with German filmmaker Hito Steyerl and, with Saner, plans to co-host an outdoor, immersive overnight workshop and performance. —Zachary Whittenburg

Stephanie Troyak

Stephanie Troyak brings the awkwardness of an ungainly colt to the soloist role in Pina Bausch’s Seven Deadly Sins, a coveted part that she snagged in her first season with Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch. Her sprawling length blossoms into sweeping gestures of equal parts abandon and exactitude; her grit and acting chops are put to good use during the more disturbing sections of Bausch’s psychological epic. “I feel at home in Pina’s mix of theater and storytelling,” says Troyak, a 24-year-old alum of the renowned Booker T. Washington High School for Performing and Visual Arts in Dallas.

Seven Deadly Sins. Photo by Jochen Viehoff, Courtesy Troyak

Troyak’s controlled wildness, perfect for pieces like Bausch’s Rite of Spring, was developed during her time with Batsheva—The Young Ensemble, where she danced the earthy works of Ohad Naharin, Sharon Eyal and Danielle Agami. While at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and Batsheva, she tried her hand at choreography and has not stopped—much like the whirlwind swirl of her career. —Nancy Wozny