Against All Odds, Six Dance Organizations Find Ways to Thrive in Hard Times

Over the past three years, most dance organizations have faced major challenges—at times, existential ones—due to the COVID-19 pandemic and, more recently, economic and political volatility. Emergency relief funds, and lower expenses while in-person events were suspended, helped delay the financial impact of these forces on some established arts and culture nonprofits, many of which reported operating surpluses and historically high contributed revenue (i.e., donations and grants) in 2021. In general, however, those conditions didn’t last long and now expenses are high, earned income from ticket sales is limited, touring remains complicated and budget deficits loom large. Against these odds, a few organizations are doing better than ever, thanks to innovative partnerships, new business models, increased commitments by funders to artists and communities of color, or some combination thereof.

Setting It Up

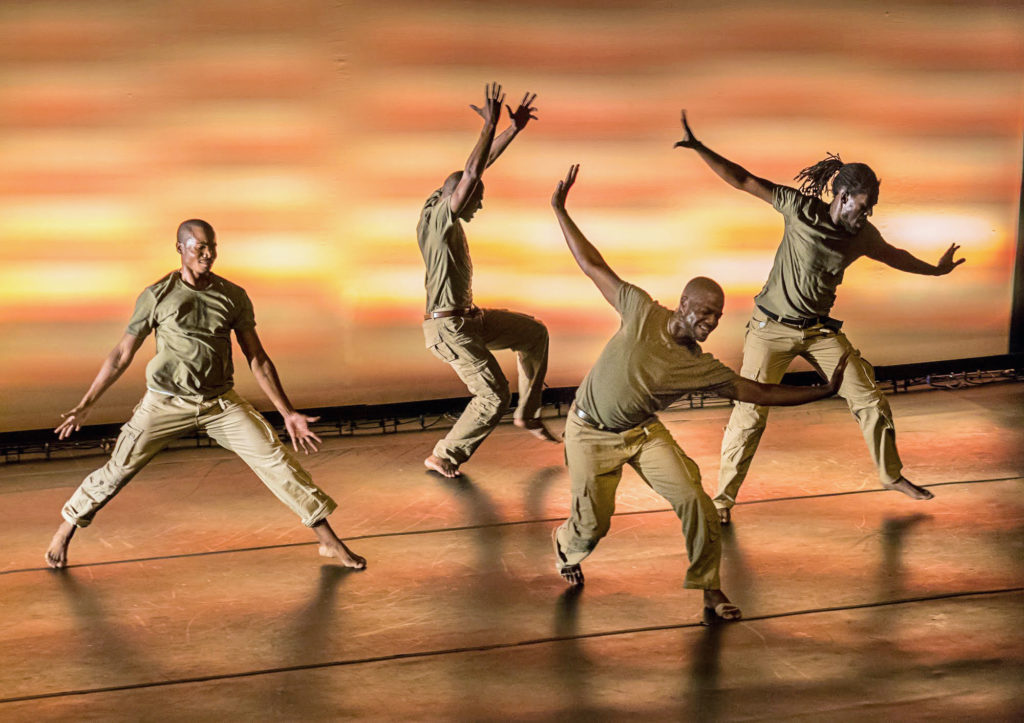

Philadelphia-based DANCE IQUAIL! entered 2020 primed for financial growth and a higher national profile, through touring engagements in progress with at least 10 dance presenters. The pandemic threw cold water on all of those leads, though the organization did receive a CARES Act grant from the National Endowment for the Arts and other COVID relief funds, says executive artistic director Iquail Shaheed, PhD. Without performance fees and ticket sales, however, Shaheed says that public support “would’ve evaporated” if the organization wasn’t also eligible for foundation grants through its mission to use dance “as a conduit for combating issues of social injustice.”

Diversified funding kept DANCE IQUAIL! from backsliding and actually accelerated its achievement of certain goals. “Back in 2019, I didn’t expect to be able to offer dancers 15-week contracts until June 2023, but we rolled those out in January 2022,” says Shaheed, who also serves on the boards of Dance/USA and the International Association of Blacks in Dance. “We’re about 18 months ahead of schedule.” When touring negotiations finally resumed last fall, Shaheed was ready to pick up where each of them left off. “I just booked one of the strongest relationships with a presenter that I’ve ever had, for the end of 2024,” he says. The company’s touring plans now extend into 2026.

Like many dance organizations in densely populated urban centers, New York City’s Amanda Selwyn Dance Theatre earns revenue through contracts with local schools to provide dance education in the classroom. In turn, these contracts support the company’s performances, typically produced at a net loss. When COVID protocols paused community engagement programs indefinitely, many companies were forced to furlough any teaching artists who hadn’t already left the field. ASDT executive and artistic director Amanda Selwyn, who founded the company in 2000, remembers well the hits to her partner schools’ budgets during the financial crisis that began in 2008. Over the course of the next decade, Selwyn had steadily rebuilt those relationships. “Going into the pandemic, we’d just had our most robust year of arts education yet, with about 20 programs,” she says.

In 2021, in part to address the financial hardship for low-income parents who need childcare during summer workdays, the New York City Department of Education and Department of Youth and Community Development launched six free weeks of educational activities, plus breakfast and lunch, called Summer Rising. ASDT, as an organization with two decades of experience with (and contacts at) neighborhood schools through its Notes in Motion curriculum, was well-positioned to be involved. With 12 grants totaling $300,000, ASDT was able to provide 20 to 30 hours or more of instruction, four days a week for six weeks, in as many as 12 different sites per day. “We could provide almost full-time employment for artists, and we hired about 45 of them,” Selwyn says. More than a third of Notes in Motion’s total sessions since 2000 occurred during the 2021–22 school year, when it reached more than 54,000 students—10 times the program’s size before COVID.

Building Connective Tissue

For both Nashville, Tennessee–based company New Dialect and nonprofit producer Works & Process at the Guggenheim, growth since 2019 has been driven by knitting tighter networks that are more artist-centered.

“Even before the pandemic hit,” reflects New Dialect founder and artistic director Banning Bouldin, “we were approaching our 10-year mark asking ourselves: Are we going to move in an institutional direction, expanding our capacity to bulk up our operations and programs? Or do we want to move forward in a more agile way that allows us to act more like artists and less like a traditional nonprofit?” Bouldin says the group decided to reconnect with its original objective, “to be an ecosystem-builder here in Nashville for contemporary dance artists to have a sustainable practice, collaborate and get paid.”

The immediate effect of the pandemic on New Dialect—the cancellation or indefinite postponement of nearly all of its 2020–21 engagements—“stripped us to the studs, financially, and forced us to make moves immediately,” says Bouldin, “away from conventional ideas about how a dance company should operate.”

That shift paid off. New Dialect is on track to engage 47 collaborators during its 2022–23 season, more than twice the number involved in its 2018–19 season. This extended family lives in California, Florida, Nevada, New York, North Carolina and Tennessee, plus Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Israel and Sweden. A performance and installation being developed with RUR Architecture DPC is slated for presentation in Tokyo later this year.

New Dialect’s experimentation with alternative models for touring and operating, which position it as both a co-producer and a content creator, isn’t occurring in a vacuum but is encouraged by the company’s membership in two professional-development cohorts: the Creative Administration Research (CAR) program, at the National Center for Choreography at The University of Akron, and the Momentum program, organized by regional nonprofit South Arts. “It’s been helpful for us to recognize, and to say out loud, that things are not going back to the way they were,” says Bouldin of conversations with her CAR thought partner, John Michael Schert, and Momentum colleagues in four other southern states. “So what does ‘forward’ look like?”

Works & Process, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, produces fully funded, studio-to-stage opportunities for artists to make new work, which executive director Duke Dang likens to the “farm-to-table” movement in culinary arts. Established in 1984, the organization is independent but partners with the Guggenheim, Lincoln Center and the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts to present performances. Over the past three years, Works & Process has built and deepened relationships with a dozen residency partners, located in six counties across the state of New York, that allow it to offer artists housing, transportation, round-the-clock access to studio space and weekly wages of $1,050, plus $400 per performance, per person. Fundraising to support this investment in the people who make the product increased the operating budget of Works & Process from below $1.5 million before the pandemic to more than $2.3 million in 2022. In 2019, 26 percent of the organization’s expenses were fees paid to artists; last year, that portion grew to 41 percent.

Just as Bouldin and her peers are interrogating industry habits that limit organizational growth and mobility, Works & Process is doing its part to move the needle away from methods and policies that are detrimental to working artists. Dang points to tour presenters’ exclusivity clauses (which limit when and where else a dance company can perform), challenging the long-held assumption that alternative events near a booking dilute sales and thus limit the presenter’s earnings. For example, Dang saw no reason to prevent the Ladies of Hip-Hop from accepting an invitation to perform across Central Park just two days before the showing that concluded their Works & Process residency to develop Black Dancing Bodies. “They performed on Friday at Lincoln Center and then on Sunday at the Guggenheim,” Dang says, “and why not? They were prepared. The more opportunities artists have, the better off they are.” In March 2021, Black trans femme choreographer Courtney Washington Balenciaga’s Masterz At Work Dance Family performed at the Oculus and then the Guggenheim through Works & Process—on the same day.

Agency Through Expansion

A persistent narrative about virtual programming is that it disincentivizes in-person attendance and therefore makes donor engagement more difficult. That hasn’t been the case at Ballet Hispánico, whose annual in-person audience is now twice the size it was before the pandemic, while its virtual audience has also grown more than 300 percent over the past three years. In 2021, its virtual gala raised more than $850,000. “A lot of folks said to us, ‘I don’t care about a table, I just want to see you survive,’ ” says artistic director and CEO Eduardo Vilaro. “What that allowed us to do was, one, bring back everyone who’d been furloughed and, two, anyone who had taken a pay cut was given all their back pay.” Ballet Hispánico’s 2020 budget, just under $12 million, represented nearly 50 percent growth over 2017. Its total 2021 revenue surpassed $27 million, thanks in part to a transformative gift from philanthropist MacKenzie Scott and an America’s Cultural Treasures grant from the Ford Foundation.

This recent leap into America’s top tier of dance organizations by audience and budget size makes Ballet Hispánico more attractive than ever to visibility-minded sponsors, Vilaro says. Whereas the company’s home seasons were previously presented at the 1,500-seat Apollo Theater and the 470-seat Joyce Theater, it now performs at New York City Center, “where you can bring more than 5,000 people through the door in a single weekend,” he says. “That shifts the conversation with a potential corporate sponsor.”

Speaking with Dance Magazine via Zoom from the company’s building, on a stretch of West 89th Street recently renamed Ballet Hispánico Way, Vilaro exudes gratitude and a cautious optimism informed by years of watching trends in arts funding come and go. “If you’re interested in us, know that we have an agenda and a way we feel we deserve to be treated,” he explains. “That ugly head still rears itself from time to time, that says, ‘I need this Latino thing right here, right now.’ The tokenism jumps out, and when it does I let staff know that, because of our profile and our cultural stance, it’s okay to say, ‘No, we don’t have to accept this.’ ”

Another Path Forward

For now, an entrepreneur resists the nonprofit model.

As KM Dance Project enters its second decade, founder and artistic director Kesha McKey seems satisfied with what the New Orleans–based company has accomplished without becoming a 501(c)(3) nonprofit. Through fiscal sponsorship from a local organization called Dancing Grounds, KMDP is eligible for certain types of grants, from funders within and beyond Louisiana. In recent years, those grants have come together harmoniously, allowing McKey and associate director Catherine Caldwell to make bigger, longer-term plans.

In 2019, after cobbling together $10,000 to $15,000 dollars year after year to make and show work, McKey received a $90,000 National Dance Project production grant for Raw Fruit, which included a $35,000 touring subsidy, “which is, of course, unheard of for small dance companies like this one in New Orleans,” she says. She also received a choreographic fellowship through Urban Bush Women’s Choreographic Center Initiative. The pandemic interrupted McKey’s original plan for Raw Fruit but did lead to federal funding for KMDP through the U.S. Small Business Administration. Because McKey had built a private studio for dance in her backyard, she and Caldwell could control safety protocols and continue hosting Raw Fruit rehearsals. McKey then received a pair of grants from the National Performance Network, a second choreographic fellowship with Urban Bush Women and a fellowship from Dance/USA, the national dance service organization.

“All these things came in, one after the other, to sustain us,” says McKey. “I’m also good at holding on to some money and making it do what it needs to do.” While hitting its 10-year mark this year already tells a story of survival, “there’s something to be said about the company’s artistic growth in itself,” says McKey. “We’ve been able to dive into processes, so there’s a lot more to discover and, on the other end, what we have to show is something people notice and find worthy of money and attention.”